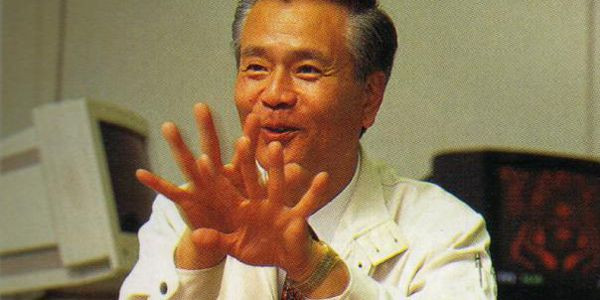

This interview with legendary Nintendo designer Gunpei Yokoi was conducted in 1997, just before Yokoi’s tragic early death. Gunpei Yokoi was a Japanese video game designer, a long-time Nintendo employee, best known as creator of the Game Boy and inventor of the modern-day D-pad, a design that nearly all video game controllers use today. Also for his contributions to critically acclaimed video game franchises Donkey Kong, Mario Bros. and Metroid.

Game and Gameplay

Morikawa: Yokoi, how do you feel about recent games?

Yokoi: There’s a huge variety of console games out now, but to me, the majority of them aren’t actually “games”. The word “game” means something competitive, where you can win or you can lose. When I look at recent games, I see that quality has been declining, and what I’m seeing more and more of are games that want to give you the experience of a short story or a movie.

After we released the Game Boy, one of my staff came to me with a grim expression on his face: “there’s a new handheld on the market similar to ours…” The first thing I asked was: “is it a color screen, or monochrome?” He told me it was color, and I reassured him, “Then we’re fine.” (laughs)

This is most obvious with role-playing games, where the “game” portion isn’t the main focus, and I get the feeling that the developers really just want you to experience the story they’ve written. So when you ask what I think of games today, well, it’s a very difficult question for me. I end up having to say that games today just aren’t games to me.

shmuplations is a personal project that aims to be a repository of Japanese game developer translations, covering primarily (but not exclusively) older arcade and console games from the 80s and 90s. You can support shmuplations on Patreon and see a list of other interesting interviews at the bottom of this article.

The essence of games is competition, and I think that’s a remnant of our past as animals, and the competition of the survival of the fittest. I think you see it reflected all through human history, how people with wealth and power want to have harems, acquire women… that kind of thing is at the root of humanity.

Morikawa: It’s true, games have really diversified now, and that “pure gameplay” aspect of games has been pushed to the sidelines. You were very active in the era when games were all about gameplay; what do you think of the scene today?

Yokoi: When I ask myself why things are like this today, I wonder if it isn’t because we’ve run out of ideas for games. Recent games take the same basic elements from older games, but slap on characters, improve the graphics and processing speed… basically, they make games through a process of ornamentation. That’s where we’re at with console games today, but I believe there are still more basic varieties of competitive gameplay to be discovered.

I said the same thing when I quit Nintendo and started my own company, Koto Laboratory; however, when it came down to it and the staff asked me “well, what should we do then?”, in reality I found it to be extremely difficult to think of new things. But when we released the keychain game Kunekuneccho, which is really an old style game, and it was commercially successful, then I felt like my ideas were somewhat vindicated.

In 2010, there was an exhibit in Japan showcasing Yokoi’s lifetime of creation. This case displays his Game and Watch series, which epitomize the “gameplay first” attitude described above.

Morikawa: I think I might be one of the culprits responsible for this phenomenon you describe, of games no longer being games anymore…!

Yokoi: But the things you’ve made were never intended to be the kind of games I’m talking about. You created them from the perspective of what you think console fans want today, and I definitely don’t think there’s anything wrong with that.

Graphical Realism

Morikawa: Just as you said, the games which are taking basic gameplay elements and dressing them up with some novelity are the ones that are selling best today. And we definitely don’t want to make major, “big” games at MuuMuu, so in a certain sense we’re out of step with the trends ourselves. We’re making games which are the complete opposite of the traditional games you described, but I agree completely with the core of what you’re saying, that what is mainstream in gaming today is, in a certain sense, decidedly not “game”-like.

Yokoi: Yes, I think we understand each other. No matter how much CG approaches reality, it will never be able to overtake real visuals. There will always be an unsurpassable limit.

Morikawa: In Ganbare Morikawa-kun 2 Gou (known as “Pet in TV” overseas), we didn’t try to overdo the visuals—we left them kind of cheap and stylized. Photorealism isn’t always the best way to go. Nowadays consoles have gotten a lot more powerful, and you can display many things that were impossible in the past. You have many more colors to work with, you can use video, and sampling is available for music. Nevertheless, I don’t think there’s any future in pursuing photorealism. I mean, by the 17th century artists were already starting to abandon photorealism as a style, you know? I think pursuing it will only increase the amount of labor in games development, but I don’t sense a big future in it.

MuuMuu’s game Ganbare Morikawa-kun 2 Gou, aka Pet in TV. As Morikawa explains below, the game (perhaps unjustly) received negative reviews for it’s “cheap” graphics.

Yokoi: Do these playworlds really need to be that photorealistic, I wonder? I actually consider it more of a minus if the graphics are too realistic. There’s a similar line of thinking in the entertainment world—using soft focus lenses when women are filmed, for instance. When that is done, each person can project their own conception of “beautiful” onto the woman being filmed, and everyone will see their own personal Venus.

If things are too realistic, there’s no room for your imagination, and the reality of those faces you thought were beautiful will be revealed. Or to use another common expression, it’s actually more erotic when a woman leaves some skin covered. Even if a video game doesn’t have the power to display very complex graphics, I believe your imagination has the power to transform that perhaps-unrecognizable sprite called a “rocket” into an amazing, powerful, “real” rocket.

Morikawa: We must not steal from players the ability to add their own imagination to what they see. As designers, we show them the dotted lines where they’re supposed to cut, but we must leave it to the player to do the cutting. If we take that away then there’s no room for imagination. Unfortunately the trend today does just that. There’s too much fanservice and catering to the player, doing everything for them. RPGs are especially bad about this: they’re like those all-in-one vacations people take, where every last detail is neatly tied up and taken care of for you. They set you on one linear path and there’s no room for your imagination to roam.

Yokoi: Television has gone from black and white to color, and now that we’re seeing high-definition tv it’s almost too detailed. You get that problem I mentioned, of seeing wrinkles of beautiful faces. Since television is mainly a medium for information, I think it’s better for it to be more clear, but games don’t require that. I think the world of a game feels larger when you can use your own imagination.

Designing the Game Boy

Morikawa: Hearing you say that, I feel like I understand a little better why you chose to make the Game Boy monochrome. And it wasn’t a technological problem that made you choose a monochrome screen, right?

Yokoi: The technology was there to do color. But I wanted us to do black and white anyway. If you draw two circles on a blackboard, and say “that’s a snowman”, everyone who sees it will sense the white color of the snow, and everyone will intuitively recognize it’s a snowman. That’s because we live in a world of information, and when you see that drawing of the snowman, the mind knows this color has to be white. I became confident of this after I tried playing some Famicom games on a black and white TV. Once you start playing the game, the colors aren’t important. You get drawn, mentally, into the world of the game.

Morikawa: That’s a very bold decision. It reminds me of the first Macintoshes with monochrome screens.

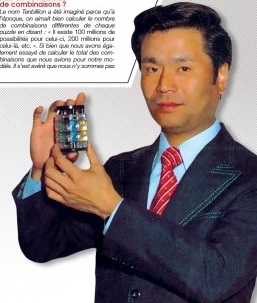

Yokoi poses with the Ten Billion puzzle toy he designed in 1980. Yokoi was thinking about returning to toy design; it would have been fascinating to see him come full circle if not for his tragic death shortly after this interview.

Yokoi: Actually, it was difficult to get Nintendo to understand. Partly, I used my status in the company to push them into it. (laughs) After we released the Game Boy, one of my staff came to me with a grim expression on his face: “there’s a new handheld on the market similar to ours…” The first thing I asked was: “is it a color screen, or monochrome?” He told me it was color, and I reassured him, “Then we’re fine.” (laughs)

Morikawa: Color screens also drained the batteries very quickly too.

Yokoi: When we were designing the Game Boy hardware, we took into consideration what kind of software was going to be made for it, and I think that approach resulted in a very efficient product. Hardware design isn’t about making the most powerful thing you can.

Today most hardware design is left to other companies, but when you make hardware without taking into account the needs of the eventual software developers, you end up with bloated hardware full of pointless excess. From the outset one must consider design from both a hardware and software perspective.

Game Design: Visuals vs. Controls

Morikawa: What is your process for making games, by the way?

Yokoi: I first take the character (or characters) which you’re going to control and replace them with a dot as a placeholder, then I think about what kind of movement would be fun. Basically I’m trying to put myself in the player’s shoes and figure out what they would enjoy. Also, when I make characters I try to design them in a way that teaches players how to play the game. In other words, if an enemy looks too pretty, they won’t seem like an enemy to the player. But if you give them an enemy-like appearance, then the player won’t need to read the manual or anything to know “oh, I’ve got to avoid this guy.”

Recently there’s been some amazing polygonal fighting games, but when you project anything onto a flat, 2D television screen, in the end we’re just talking about hitboxes. That sense of three dimensions is only for visual effect. Once you start playing the game that depth is unrelated to the gameplay: whether the sword your character swings actually hits its target is just a horizontal, two-dimensional measurement between hitboxes.

Morikawa: My process is the reverse: I start with the visuals first, then figure out movement. In the beginning TV was only capable of showing live broadcasts, then VCRs allowed videos, and gradually the television absorbed more and more new media. Game consoles, too, feel like just one form of “television peripheral” to me. So yeah, when you think about it that way, there’s nothing especially novel about games: they’re just one more kind of image that televisions can display.

Current and Future Projects

Yokoi: When I was a kid, there were so many things I wanted to do that weren’t possible because they were too expensive or the technology wasn’t there. Now that 10 or 20 years have passed, those ideas I had given up on can actually be realized. The “My Puzzle” amusement machine 1 is one of those ideas from 20 years ago. Had I tried to make it then it would have cost around 30 million yen (roughly 300,000 USD). (laughs) There were no video printers back then either. So in that sense, I think we have a lot of opportunities today to fulfill the dreams of our youth.

Morikawa: I’m 38 now, and there’s a part of me that’s very tired, that wants calming things. I think I want the faces in my games to not be drawn realistically, but just to use black and white and simple lines. That way I can leave things to each player’s individual imagination. If I make the face a beautiful one, then players will only ever see what I intended to present, and all other possibilities are lost.

I think games today are undergoing a kind of inflation similar to what Hollywood films are going through, leaving behind interesting stories and just focusing on CG and visuals. Movies like Independence Day and The Lost World are totally uninteresting outside of their visuals, and I think people are going to get tired of it. I think the same is true of games: they’ll reach a certain point of visual impressiveness, but then what? For MuuMuu’s game “Pet in TV” everyone asked me why I only used 16 colors for everything, despite the capabilities of the Playstation to do far more. But I felt the game would not be improved upon if I used full color. Likewise, the Playstation can handle about 10 times as many polygons, but I wanted to make a bright toylike world, not something realistic. One of our qualities as Japanese is supposed to be our creativity within meagre means; when it comes to games and the new hardware, it seems like everyone has forgotten that!

Yokoi: Yeah, it’s like they want gyoza stuffed with caviar or matsutake. (laughs) In any event, I’ve been thinking about moving away from television with my future work. Imagine if I show you a toy on the table here, you’d see it and think “oh, that looks fun to play with.” But if I take the same toy and put it on a television screen, suddenly people think “wow, this looks dumb.” And that’s what I mean about reality having such a stronger pull than television visuals can ever hope to match. One never tires of the basic movements of a real toy doll or human figure. Now I’d like to create something real like that, even if it’s something simple and cheap. If people find it entertaining, they’ll play with it for a long time.

Morikawa: Personally, collecting rocks is my new hobby. I like touching and holding them in my hands. Until recently I’ve spent most of my free time playing video games, but video games only activate a certain part of your brain, and their sensory experience only extends to sight and sound. It’s been ages since I let my other senses have some fun! So I’ve recently gone back to non-game activities: going fishing, casting a line, feeling the body of the fish when it’s caught. Maybe I needed this to restore the balance in my life.

Yokoi’s tombstone lists his proudest achievements at Nintendo:

- 1968 Ultra Machine

- 1973 Laser Clay

- 1980 Ten Billion

- 1980 Game and Watch

- 1989 Game Boy

Other interviews at shmuplations you may enjoy:

- Shigeru Miyamoto x Yuji Naka - 2001 Developer Interview

- Street Fighter II - 1991 Developer Interview

- Final Fantasy VII - 1997 Developer Interviews

shmuplations is a personal project that aims to be a repository of Japanese game developer translations, covering primarily (but not exclusively) older arcade and console games from the 80s and 90s. You can support shmuplations on Patreon. Republished with permission.