Vanity Fair has a fascinating piece on the rise, fall and reboot of Microsoft. The story is really about leadership; from the days of Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer; to Ballmer succeeding as CEO; and finally to Satya Nadella. It's a great piece and definitely worth reading.

I'm a big admirer of Ballmer, but must call him out on something he was quoted on in the article:

"The worst work I did was from 2001 to 2004," says Ballmer. "And the company paid a price for bad work. I put the A-team resources on Longhorn, not on phones or browsers. All our resources were tied up on the wrong thing." Who shoulders the blame is a matter of debate, but the fact is neither Ballmer nor Gates stopped the failure from happening, even as almost everyone else saw it coming.

It's not fair to say everyone saw it coming. It wasn't until the second iPhone and the arrival of the App Store that the larger tech press realized something game changing was about to happen; before then, the narrative was still that Blackberry and Microsoft had the lead in mobile.

Ballmer's comment that they missed on mobile because the company's resources were tied in Longhorn and Vista has merit. What the Vanity Fair article didn't mention was that Microsoft practically scrapped Longhorn and started over on Vista. After the Longhorn debacle, the Windows team went on a three year sprint to get Vista done and in the process burned a lot of good people out.

However, as I pointed out in this column's inaugural post, Ballmer didn't really have a resource issue – he had a resource allocation problem. Ballmer underestimated the importance of mobile. The industry had shown little profit potential up to that point and Microsoft already had second place share with arguably the best product and rapid growth; was there an imperative to invest so heavily in it?

What he missed was a tectonic shift in computing. Not just in terms of computers shrinking to pocketable devices, but what it meant to win in that environment. Tech pundits have written ad naseum how Microsoft, obsessed with preserving its hegemony in Windows, was ill-equipped to win in mobile. I think that's right, but it goes a lot deeper than that.

It wasn't just misdirected ambition, it was about Microsoft's very identity.

The history of PCs can be roughly divided into three phases: the rule of geeks, the rise of IT and finally, the realm of the every-person.

The rule of geeks is obvious. Those are the days of command line prompts, beige colored shells and glowing green screens. Computers were the exclusive domain of techies who played with electronics more out of passion than profit.

Then, with the help of the Macintosh and Windows, PCs became a real business – a whole new industry called "Information Technology" was born where none existed before. You had cadres of IT professionals and engineers who built their lives on PCs. You had office workers listing Microsoft Office as a skill on their resume. Eventually it became a world that Microsoft absolutely ruled.

Microsoft did the best job developing platforms for IT professionals and engineers. PC interfaces didn't need to look pretty; it was better to have extensive feature sets and endless customization options even if it meant only the most committed could learn it all. That's what IT support and training sessions are for anyway.

It was more important to make the platform open and malleable than stable and intuitive.

Apple, on the other hand, made better looking computers with closed environments that IT workers didn't particularly appreciate. Those who weren't interested in tech but used computers for work didn't really care either. Doing the most basics of tasks -- work with office documents most probably – and nothing more.

Computers weren't lifestyle products; they weren't things the average person played with for fun; and outside of artsy circles like graphic design, they certainly didn't care whether the computer was Dell or Apple as long as it got the job done.

Electronic brands were more functional than emotional or symbolic. It was a world where Dell was more influential than Apple.

Those of you too young to remember may forget, but back then, computers costed thousands of dollars. It was a big purchase and often the most expensive item in the living room. It was an era where "a computer on every desk" was not just a mission but an ambitious one.

It was an environment that favored Microsoft, a tribe of engineers and office workers who made products for themselves. And they thrived.

Then something strange happened: technology became mainstream. First it was the Internet, which brought so much value -- in particular, communication and news – that a wider audience was pulled in. Then we had the crazy Internet bubble of the late 90s that caught the world's attention. It seemed like everyone had at least a distant relative that had raised millions based on an idea they sketched on a napkin.

Then it was music. Free music.

Services like Napster and later on iPods made music so easy to get and share, everybody looked for it. More people got comfortable with using technology beyond CD players, like downloading software to your PC, searching websites, syncing the MP3 player. A generation of people learned to use technology for fun because of music.

Then it was Friendster, MySpace and Facebook. Social networking became so prevalent that it became strange for someone not to be on one. Grandmas asked younger relatives to help set up a profile. The world was flipped upside down: no longer was it about IT workers and engineers, computers became a realm for the every-person.

Phones were of course the clearest harbinger of this sea-change, especially when they became powerful enough to be used more like computers and great cameras than actual phones.

Microsoft went from being the most popular kid in the room – the leader goth at the goth party – to the most uncool person in the fraternity house. Their traditional strengths of enterprise-ready platforms, targeted for IT workers, were handicaps in creating for the every-person. The every-person didn't care about feature sets; they wanted intuitive, simple and beautiful products.

Windows is ugly. Windows is messy. Windows has too much stuff.

It is in this realm that, conversely, Apple's strengths finally matter. Their emphasis on clean, controlled interfaces and sleek hardware is one that the new, bigger market actually appreciates.

Apple built a cult of want where people lust after Apple products – if they can afford it. Every time iPhones and iPads launch to long lines and go out-of-stock only serves to reinforce that power, and which the press are happy to broadcast. The Apple brand is one that people feel proud to associate with.

Technology today is more about how it makes you feel than about what it does.

This brand advantage has become a real problem for Microsoft. When something goes wrong in Apple's world, suspicion is first directed towards the third party. When something goes wrong in Microsoft's world, blame is immediately placed on brand associated with malware and viruses. I've seen this over and over – it's a quicksand Microsoft can't seem to get out of.

So when the iPhone debuted, it clearly outclassed everyone else's. The first iPhone had enough limitations (such as price) that people weren't quite sure whether it was the next iPod or the next Apple Lisa; but the iPhone 3G laid those doubts to rest.

Give credit to Ballmer: he had the intellectual honesty and balls to restart Longhorn as Vista, and Windows Mobile as Windows Phone once he saw the former had a limited lifespan in the iPhone world. He was just too late.

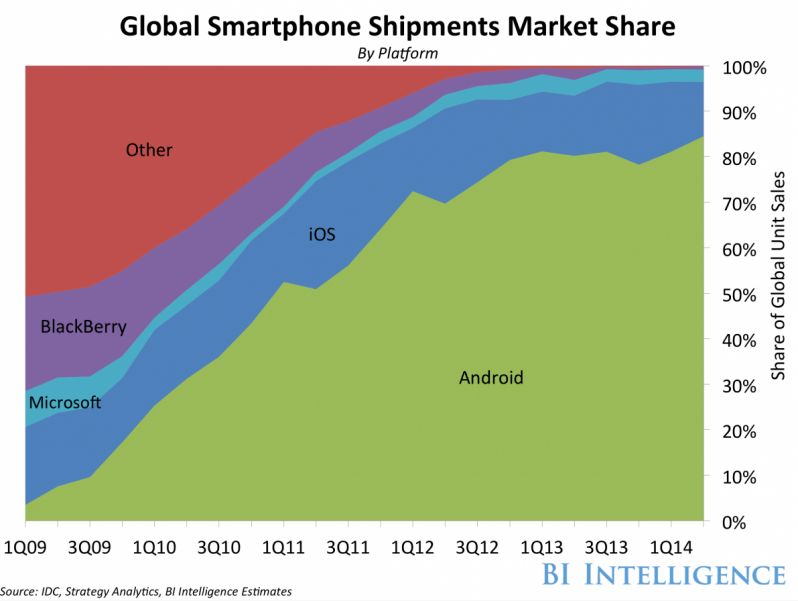

Google jumped in with Android where Microsoft should have – not innovating much at first, content to follow iOS' lead though now Android is arguably ahead – and the rest is history.

Source: Business Insider

Not only was Microsoft distracted by Longhorn – and subsequently Bing – but Ballmer underestimated mobile; Microsoft simply lacked the DNA to win the every-person.

Even if Ballmer was keyed in to the mobile opportunity, I don't know that the outcome would be different. Microsoft would have continued to refine a product for the IT worker and not the every-person; Apple would still be the first to make waves and earn enormous profits; and Google would have surfed in to rule in market share.

Of course, the last chapter on Microsoft hasn't been written yet. They may have lost on mobile, but another tectonic shift is well announced: cloud computing. That's a story for another day.