Next time you play a video game, look down at the controller in your hand. Is it comfortable? Does it work well with the game you're playing? Are your fingers all being used efficiently? If you could change one thing, what would it be?

Next time you play a video game, look down at the controller in your hand. Is it comfortable? Does it work well with the game you're playing? Are your fingers all being used efficiently? If you could change one thing, what would it be?

About 10 years ago, after permutations ranging from Atari 2600 joysticks to Sega Genesis "C" buttons, console game controllers arrived at something resembling a standard. A modern console controller must have: Two clickable sticks and a D-pad, four face buttons, a pair of triggers, a start and options button, and a pair of shoulder buttons. That configuration has held steady for at least one full console generation. The modern PS4 controller, Xbox One controller, and Nintendo Switch Pro controller all have more or less the same functionality as their predecessors. Of course, some people still think it's time for new ideas.

The Dreamcast and later the Wii U experimented with adding a screen to the controller, reasoning that more information by your hands could make games more compelling. Sony and Nintendo have added motion controls with varying levels of success. Valve's recent Steam Controller adds a rumbling trackpad in place of the right thumbstick, which allows for more precise movements closer to using a mouse. They also added two programmable buttons to the underside of the controller.

And then there are controllers that have been made purely to experiment with joyful and interesting ways to interact with technology. Here I am at the experimental controllers section of the 2016 Game Developers Conference messing around with Hello, Operator, a game you play using an old phone switchboard.

Other smaller innovations have included the Switch Joy-Con's "HD Rumble" for more detailed physical feedback, or the DualShock 4's little-used trackpad and annoying glowing lightbars. Even small things, like a switch between wireless connection protocols or the switch from mini-USB to micro-USB cables, can make a difference.

One idea that stands out

Custom controllers from boutique companies like Scuf and Razer often have flashy paint jobs and marketing copy full of boasts about the high quality of their parts. They usually feel better in your hands and can even give you a competitive advantage over the controller that came with your console. But until fairly recently, most custom controllers didn't attempt to fundamentally update the overall design of the game controller. Enter under-buttons.

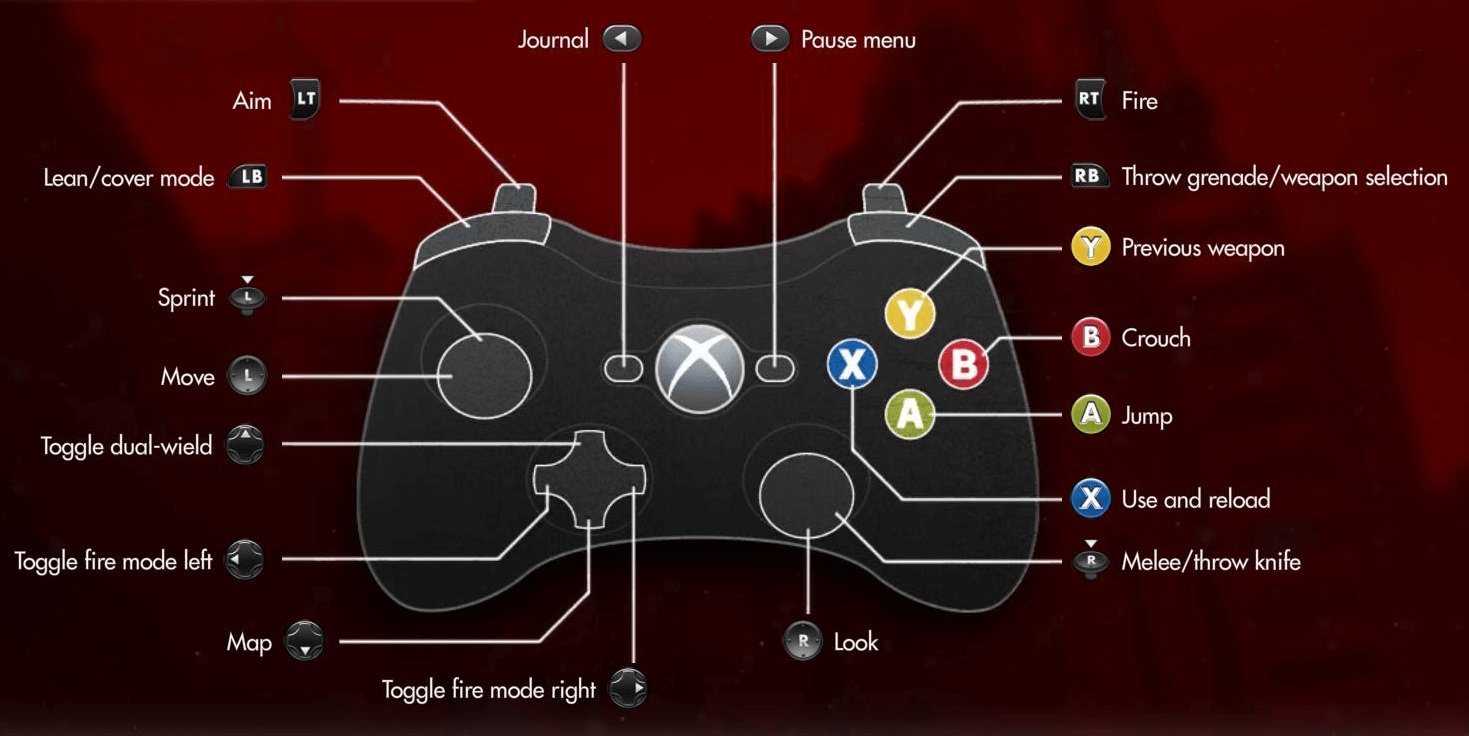

The controller layout for Wolfenstein: The New Order, which more or less matches the control scheme used by almost every modern first-person shooter.

The standard game controller works as well as it does in part because most modern games have been designed around it. But if you look at which buttons are assigned to which fingers, it's clear that it could be better optimized for the human hand. Each index finger is responsible for two buttons, and each thumb is responsible for six buttons. All while six fingers---middle, ring, and pinky on both hands---just sit there doing nothing.

Game controllers are theoretically designed to allow people to easily input the largest number of button combinations with a minimum of physical movement. That's actually similar to how many musical instruments work, particularly woodwinds. I play saxophone and other woodwinds, and each instrument I play has evolved over centuries to be as efficient as possible. Check out how my left hand sits as it presses keys on a tenor saxophone:

Taking into account the thumb-operated octave key on the back of the horn, the five fingers on my left hand are able to operate 13 different buttons without dramatically changing position. Those buttons let me input a variety of notes, many of which are modified by the nine buttons my right hand can press just as easily. To hit all those buttons, I use every single finger on both hands (aside from my right thumb), as well as my palm and the side of my index finger.

The first saxophone was engineered by the Belgian inventor Adolf Sax in the mid 19th century. The horn may be coming up on its bicentennial, but it's actually a relatively new instrument that was more consciously designed than the older instruments---flute, clarinet, oboe---that inspired its key layout. Mr. Sax designed the saxophone to be maximally efficient and versatile, and other instrument makers have refined his initial design over the years.

Video game controllers have actually followed a similar trajectory. Some specific goals are a little different---I don't think most controller manufacturers are striving for musical-instrument-levels of complexity---but their big-picture approach is similar. Slowly but surely, game controllers add more buttons, each of which theoretically allows for more flexible and expressive play. If you manage to snag an SNES Classic this September, put one of those controllers next to your wireless PS4 or Xbox controller to see what a difference a couple decades makes. The question now is, "what's next?"

The paddles on the underside of the Xbox One Elite controller, as seen on Microsoft's promotional site.

Last winter I bought an Xbox One Elite controller, Microsoft's high-end game controller designed for PC or Xbox One. It's much heavier and sturdier than a standard Xbox One controller, and you can easily swap out the thumbsticks and D-pad with magnetic alternates. Those are all nice features, but as I wrote at the time, I was much more impressed with the four programmable "paddles" located under the controller, which aim to make use of a couple of my fingers that were usually just sitting there. It was an actual, clear-cut new idea for how a game controller might be laid out.

Since then, I've become fascinated by the potential advantages you can gain by adding buttons to the back and bottom of a controller. The idea stands out to me because it offers such a clear improvement on an existing design without actually requiring games themselves to be designed any differently. By making it easier to press more buttons more efficiently, players can interact with existing games more easily. It's not just about efficiency or gaining a competitive edge---it can also make games more comfortable to play.

To find out more about the ongoing quest to make a better video game controller, I recently got in touch with three designers behind three of the most prominent custom controllers: Duncan Ironmonger, CEO of Scuf Gaming, whose under-paddle patent Microsoft licenses for their Xbox Elite Controller; Chris Mitchell, director of product for controllers at Razer, whose Raiju PS4 controller experiments with slightly different ideas and achieves similar results; and Carl Ledbetter, executive creative director for Xbox Devices Design at Microsoft, who lead the team that designed the Xbox One Elite controller. I spoke with Ironmonger and Mitchell over the phone; Ledbetter answered some of my questions over email.

I learned that while everyone agrees on the problems they want to solve, no two products fully agree on the best solution. That's because it's difficult, if not impossible, to answer the question of what the ideal game controller even looks like. Each company's top-end controller approaches the idea of "a better game controller" in a different way, but if you unfocus your eyes, you can start to see a standard emerging.

The sales pitch

Custom controllers like the ones I'm talking about in this article aren't cheap. A Scuf Impact goes for $150, and while the Razer Raiju isn't available in the U.S., it goes for 150 British pounds, or the equivalent of $200, overseas. Like the Scuf, Microsoft's mass-produced Xbox Elite controller costs $150. In order for these companies to convince you to shell out that much for a controller, first they have to convince you that your existing controller isn't good enough.

Scuf's Duncan Ironmonger said that somewhere around 2010, he noticed a lot of competitive first-person shooter players using "claw" technique, wherein a player curls their right index finger over the face buttons and works the right-side trigger and shoulder button with their middle finger. Claw allows a player to keep their right thumb on the thumbstick even when jumping or crouching, which makes it easier to play more acrobatically and aim while airborne.

A demonstration of Claw Technique in Call of Duty, via SplitsandTV

"Playing claw was really how a lot of the competitive players, especially in shooters like Call of Duty, were actually able to compete at a higher level," Ironmonger told me. "If you take that general concept, two thumbs [and] two fingers to control 20-plus functions on a controller, then I think we'll all agree that by using more of your hands, theoretically, you could reduce that latency and you could become skillful and show more dexterity.

"We believed that the controller was outdated," he said, so they used Call of Duty as a model to develop their first under-controller paddles. The paddles mimic the face buttons, so instead of taking the fraction of a second to move your thumb to press a face button, you could do it instantly with one of your other fingers.

Razer's Chris Mitchell was more deferential when it came to claw grip. "I think it's presumptuous to say hey, we're gonna fix your grip style," he said. "Some people get so ingrained in a specific playstyle that it's gonna be very hard to move them away from it. But you need to get to that level where enough people see that benefit, [and say,] 'Hey yeah, I need to retrain myself to be able to use it in the way that it's intended.' And sometimes that can be challenging. It can be an uphill battle.

"We're always trying to ultimately get to that point where we cater to something that makes it just so easy and so intuitive to use. I'm not saying we're there yet, necessarily, but it's a journey in that sense."

"We believed that the controller was outdated." - Scuf's Duncan Ironmonger

The designers at Microsoft decided there was a market for people playing video games at the highest levels of skill, even while as a first-party console maker, they still have plenty of incentive to sell regular old Xbox controllers. "I think competitive players, or people who aspire to play at that level, are expecting this kind of feature for their controllers because it gives them the ability to fine-tune their controllers for better accuracy and precision," said Microsoft's Ledbetter. "At the same time, we know this level of control isn't for everyone, and a lot of gamers just want a standard [controller] that's simple and easy to use right out of the box."

Mitchell made it clear that he didn't think the PS4 or Xbox One controllers were bad to begin with. Razer doesn't feel the need to completely change them, he said, "and when you do change, you start with small things that may not always be super visible but can make a big difference in terms of feel and ergonomics and especially comfort over an extended period of time. The question is whether Microsoft and Sony at some point in time decide that these buttons on the back---basically a higher priced controller---has to be the stock controller. It could happen, but I don't think it will happen in the next two or three years."

Interesting ideas with no clear winner

I've been using each of Scuf's, Microsoft's, and Razer's flagship controllers for the past several months, rotating regularly between them. I've found strengths and weaknesses in each one.

Some quick thoughts:

The Scuf Impact PS4 controller is larger than a standard PS4 controller. It's more along the lines of an Xbox One controller in shape and size. It has hair-triggers you can set using an included plastic hook, and swappable thumbsticks if you prefer a wider range of movement. The under-paddles are lined up in rows, and the inner two buttons are stiff and more difficult to press. That's both good and bad---it makes it harder to accidentally press a paddle, but also makes it harder to press a paddle in general.

While playing Destiny 2, I assigned the inner-left paddle to be my run button, but found I was getting repetitive stress pain in my left middle finger from pressing it repeatedly. Right now I'm most comfortable using only three of the paddles, and leaving the inside-right one unused. I like the feel of the Scuf overall, though, and actually think it works great for non-FPS games like Niohand Bloodborne.

The Razer Raiju PS4 controller has several similarities to the Scuf, even as it tries some new ideas. It too has a hair-trigger mechanism, though you can toggle it simply by pressing a combination of buttons. It's also got a collection of function buttons hanging between the grips, which let you hop between two saved presets. That's a significant advantage over the Scuf, which forces you to remap buttons through an annoying process of holding a magnet under the controller while carefully pressing remappings (seriously) with no savable presets.

In placing their alternate buttons, Razer also takes a different approach from Scuf. Instead of paddles, they've placed two small triggers under the controller, as well as two additional buttons inside of the shoulder buttons on the controller's trigger-side. It's an interesting idea, though sometimes the extra shoulder buttons can lead me to accidentally hit the main shoulder button. While the Raiju has some ease-of-use advantages over the Scuf, I generally prefer the Scuf's feel.

I use the Microsoft Xbox Elite controller on PC and have grown to really like it. It's easier to customize in every respect than either of the other two controllers thanks to its included Windows/Xbox software. If you want longer sticks or a different D-pad cover, you can just pop magnetic replacements in and out, and the hair-trigger can be activated with a simple switch next to each trigger. The four under-paddles are placed such that I can easily rest my middle and ring fingers on them and press them at will. They're pretty sensitive and it's easy to accidentally press them, something that all three designers I spoke with, even Ledbetter, acknowledged could be an issue depending on the player.

Most of the time I actually like how easy it is to press the paddles, and love how I can use the included software to save a ton of game-specific presets. As much as I like the other two controllers, I've half a mind to buy one of those USB adapters that'll let me use the Elite on PS4.

"A lot of gamers just want a standard [controller] that's simple and easy to use right out of the box." - Microsoft's Carl Ledbetter

The more I've played with each of those three controllers, the more I've found myself taking advantage of the extra buttons at my disposal. I'm actually no longer sure I could comfortably go back to a standard controller. I use them for more than just first-person shooters like Destiny and Titanfall: In third-person action games like Bloodborne and Nioh, I assign my attack and dodge to the Scuf's paddles. In Final Fantasy XII, I assign the mini-map and X buttons to the Raiju's extra buttons, which actually makes a bigger difference than I thought it would. I use the Xbox Elite paddles on almost every PC game I play, from The Witcher 3 to No Man's Sky.

Ironmonger says his Scuf controllers are beginning to draw attention beyond the shooter crowd. "[FPS] was a natural place to start, as we've evolved out, we find a lot of people using it for Destiny, Halo, Gears of War... I actually just came back from Berlin for the FIFA finals [in May], a lot of people using it for sports games now. Madden, NBA, FIFA. and I think that what you'll see is, as the different games become more competitive, you're gonna see more people look for equipment that's gonna give them that edge."

Beyond just getting a competitive advantage, I've noticed that these controllers can be helpful for reducing repetitive stress and even for letting gamers who might not have full access to both of their hands use a controller more easily. I've recently found that remapping the left thumbstick "run" command to a paddle takes a lot of strain off of my left hand, and Mitchell confirmed that the thumbstick is one of the most commonly remapped buttons among Razer users. He said that they're always looking at how their controllers might help disabled gamers. "If you can make a controller that a person with certain physical challenges can play with, then you have a controller that anybody can play with."

The wide world of controller patents

Patents are a necessary part of any tech sub-industry, where people constantly have new ideas and subsequently attempt to legally protect those ideas as their own. Scuf in particular seems hard-nosed about protecting their patents; Ironmonger spent a big chunk of his introductory spiel with me discussing the many patents they've been granted over the years. The Scuf website has an entire page dedicated to the matter. The company is actually involved in lawsuits against rival controller manufacturers Valve and Collective Minds, both for allegedly infringing on Scuf's paddle design.

The Scuf workshop in Suwanee, GA.

"I'm a realist [enough] to know that people aren't respectful of people's ideas and their [intellectual property]," Ironmonger told me. "Having patents was an essential part of our controller, and that's been proven if you look now. If we hadn't patented and protected our controller then obviously, Microsoft wouldn't have partnered and paid us a royalty. I think the proof is in the pudding. But the protection for small companies when it comes to IP is an essential part of protecting what is effectively the innovation [they do]."

(Ledbetter was tight-lipped when I asked about the Scuf-Microsoft partnership: "We don't disclose partnership details but what I can say is that we really value our partnership with Scuf.")

Razer's Mitchell said that he believes that while patents can be innovation-inhibiting in some respects, in the area of game controllers, it's actually not too bad. "We all win..." he laughed and caught himself. "Well, at least the end user wins whenever there's competition. And there's a healthy competition across the board."

"It's fair to say that [patents] are a pain and they're very expensive," said Ironmonger, "[but] they're an essential component to protect your company from the big boys out there who, when they see a good idea, they're just gonna lap it up, and their marketing budgets are far greater than anything we could ever push through."

It's hard to even know what works

Each of these controllers tries something different with its swappable buttons and its paddle- and button-placement, and they're trying plenty of other less obvious new ideas as well. Each one offers some variation on a "hair-trigger" mechanism, where you can tweak the triggers to respond on a much lighter press. The Scuf and Xbox controllers offer a variety of thumbstick lengths and surfaces, along with different D-pad covers for fighting game aficionados.

Razer's Mitchell said that the biggest challenge in designing controllers is the fact that "nobody knows what they want, and everybody wants something different." He continued: "And so, it's just a lot of iteration. Also it's hard to get an opinion like, a theoretical opinion. You ask a pro player or casual player, where would you like the buttons to be placed? They cannot tell you until they hold it, and they cannot tell you if this is the perfect placement until it isn't the perfect placement. So, there's a lot of just trial and error, a lot of iteration and prototyping and doing it over and over again, and just refining it. So no one's gonna get it right on the first try.

"You ask 10 people and you get 15 opinions on what is the perfect controller." - Razer's Chris Mitchell

"A lot of people will not be able to sit there and say, the reason it's not comfortable is because the curvature of this has to be rounder, or whatever it is, right?" he said. "They sit there and say, ah, 'This is not comfortable.' Or, 'I don't like this.'"

He rattled off a list of variables he and his team had to contend with when designing the Raiju: How tall should a thumbstick be? How much should the edges on the controller shoulder be curved off? How do you design for a multitude of hand-shapes and sizes? Should you put ridges on the side of the controller for extra texture, or will it be uncomfortable? How thick should the shaft of the thumbstick be, and how wide should its radial motion be? And how do you make sure that what feels great during the first hour will still feel great after a 10-hour gaming marathon?

"That's also why competition is so very very useful," he said. "Because everyone is experimenting with new things, and then we see what is well-received, what isn't well-received, and that makes it into every controller like half a year or a year later. And then we keep going."

Each of the controllers I've tried has conclusively demonstrated that the existing game controller paradigm can be improved, even if none of them answered the question of precisely how. Scuf, Microsoft and Razer will continue to iterate on their best ideas. All the while, other technology companies like Oculus, Valve, and Nintendo will make immersive VR hand-simulators, oddball trackpad PC controllers, and funky detachable motion controls that continually suggest new ways to play.

In a few years, you might not have to shell out an exorbitant amount of money for a fancy custom controller with buttons on the bottom. There could be buttons on the bottom of the controller that comes with your console, and your unused fingers will finally have something to do. By then, of course, the people at the forefront of controller innovation will be on to some new big idea.

My money's on a foam controller that responds to how you throw it. Let's make it happen, people.

Masthead art by Sam Woolley