First-generation virtual reality platforms from major players like HTC and Oculus VR have finally delivered on the promise of consumer-grade virtual reality albeit with some significant limitations.

As they stand today, the HTC Vive and the Oculus Rift must be tethered to a reasonably fast PC to drive the experience. Fortunately, there’s a small army of researchers, engineers and developers tirelessly working to both reduce the sheer amount of processing power required to drive flagship-class VR platforms and perhaps more importantly, cut the cord.

HTC just the other day announced an add-on device for the Vive called the TPCAST, a platform-specific third-party accessory that’s available on a very limited basis.

Researchers from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), meanwhile, have been working on a solution of their own that’ll transform any tethered headset into a wireless solution.

Dubbed “MoVR,” the prototype system utilizes high-frequency millimeter waves, a much-ballyhooed technology with several potential applications. Its major shortcoming, however, is the fact that they don’t play nice with physical obstructions like walls. Even in an open room, you’d need perfect line-of-sight between a transmitter and receiver to support the sustained data rates necessary for virtual reality. Something as trivial as moving your hand in front of an equipped headset could disrupt the flow of data.

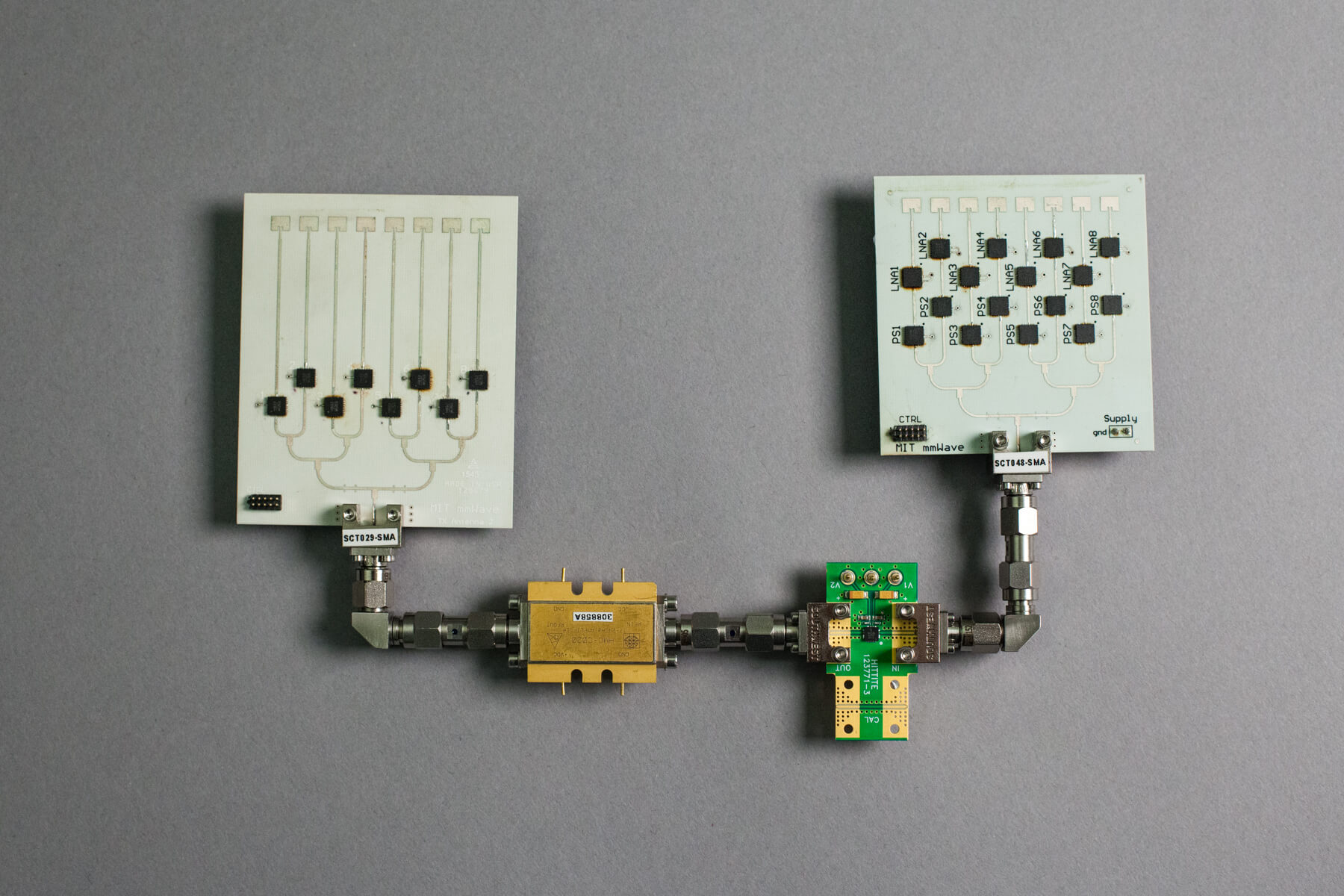

To overcome this downside, the team at MIT developed MoVR to act as a programmable mirror capable of detecting the direction of incoming millimeter waves and reconfiguring itself to reflect the waves toward the receiver on a headset. The team says its solution can learn the correct signal direction to within two degrees, allowing it to correctly configure its angles.

The current iteration consists of two directional antennas, each of which being less than half the size of a credit card, that utilize phased arrays to focus signals into narrow beams that can be “electronically steered.”

PhD candidate Omid Abari, who co-wrote a paper on the topic, says future revisions could be as small as a smartphone, thus allowing users to place several devices in a single room and enable local VR multiplayer.

https://www.techspot.com/news/67037-mit-using-millimeter-wave-technology-make-vr-headsets.html