Sean Murray, lead developer of the planetary exploration game No Man's Sky, doesn't want to dwell on negativity, tempting as it is when chatting for an interview about any game with a huge, vocal playerbase.

Sean Murray, lead developer of the planetary exploration game No Man's Sky, doesn't want to dwell on negativity, tempting as it is when chatting for an interview about any game with a huge, vocal playerbase.

"The story often is the narrative of the bad community, the toxicity, and it really annoys me that [it] commands so much of the narrative in games," he recently told me, as we chatted in a room in the Chelsea Piers fitness and entertainment complex on the western edge of Manhattan.

"You know, for two years I turned down any talk that was a talk about toxicity in gaming. I could have been the poster child for that, and we've never really talked about how bad things got at launch or whatever. I just think whilst it's interesting and a good headline and stuff like that, I just think it commands too much of the discussion around games."

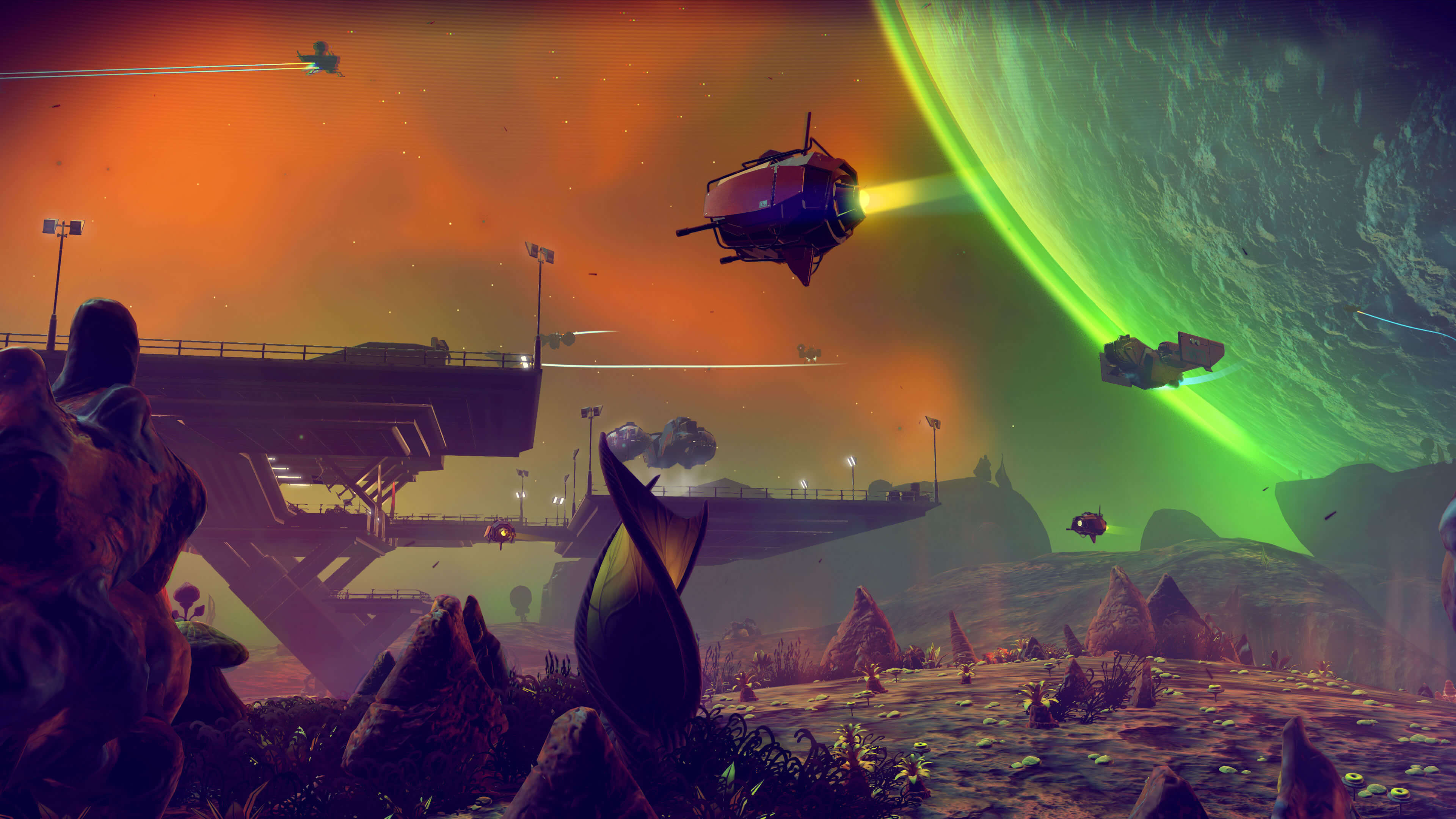

Instead, he wanted to point out something that excites him about No Man's Sky, two and half years after its rocky debut and the subsequent updates that won so many critics and fans over.

"I think what gets lost---and that Gita does a really good job of highlighting---is the nice things people do in games," he said, name-checking our own Gita Jackson, who has covered player-run governments and other fan creations and experiments in No Man's Sky for the past couple of years.

"No Man's Sky has been amazing for that: weird things that people do that you can't predict. This is lovely and really meaningful to make games in a time when people are connected enough that they can do that."

Murray: "I think what gets lost...is the nice things people do in games."

Murray has seen the best and worst of it since No Man's Sky first appeared with an incredible trailer during the 2013 Spike gaming awards. He participated in the hype leading up to its summer 2016 release, notoriously promised a multiplayer feature on national television that wasn't in the game, got scorched by fans upset with what his team at Hello Games originally launched and then slowly, surely, saw the reputation of No Man's Sky change as years of post-release updates transformed and improved it.

"I think we learned lessons, right?" he said, making one of several cheerful understatements as we chatted for a half hour.

No Man's Sky has flourished in recent years, rising in regard through the 2017 Atlas Rises update and 2018's No Man's Sky Next. While he won't release sales figures, Murray said that "last year we sold the kind of numbers a AAA game would be happy with at launch," using the industry jargon for big budget games.

"I'd love to say it's because we had this great plan and blah blah blah, but I did not think that would be the case," he said. "You know, Atlas Rises was the version we released after a year, that did really well. Each update has sold commercially more than the one before. I sat down with the team for Next and I was like, 'We should be prepared that this obviously isn't going to sell as well as the things we've done before. It's two years since launch and we went a year without doing an update, which is supposed to be death for a games-as-a-service game."

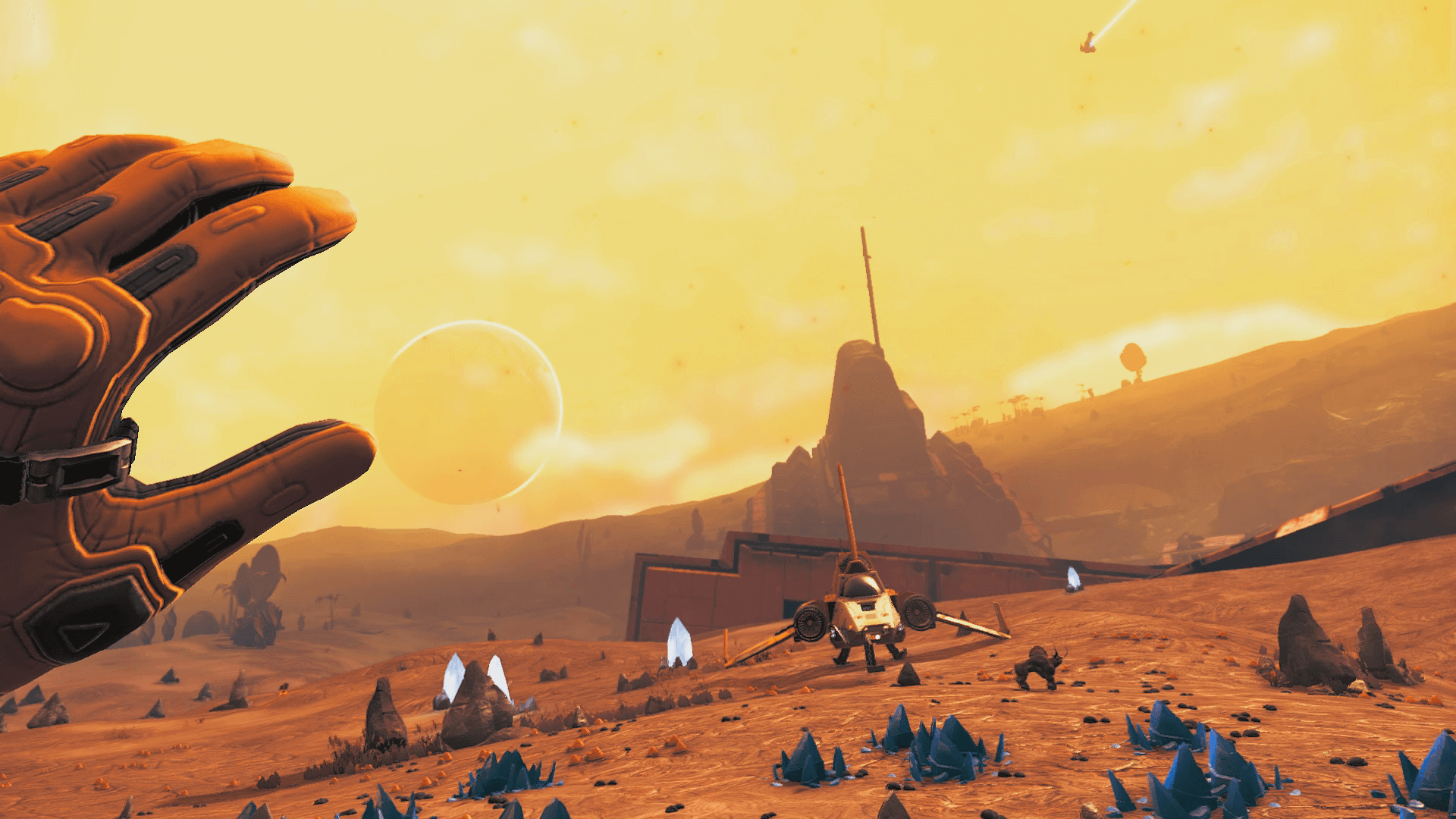

The game's next update, Beyond, includes an optional virtual reality mode, a new online "experience" and a mysterious third element Murray doesn't want to mention yet. They were going to be smaller updates, but the work on them ballooned, and it became obvious to the developers that they should bundle them. Murray figured it would help if some people, perhaps the media, could try the VR part in advance, which led him to feeling the need to show some of it earlier than he'd like.

"I wish that we weren't showing this off, if I am honest," he said as I tried the game's VR mode and he talked me through it just safely outside of the reach of my swinging arms. "I wish we could have just come out of nowhere and shown the game a couple of weeks before launch."

Talking to Murray is to experience a mix of ebullience---he is clearly proud of his game and his team---and the caution of a developer who's stepped in it before. So cautious is Murray now about not overhyping things that when I asked him if the game could ever come to Switch, he groaned and then said, "So it's not something we're talking about at the moment, you know what I mean? You must know this. We've learned the hard way to not encourage guesswork and whatever."

This caution is why part of Beyond is still secret and why Murray feels like he's been more worried about telling people what Beyond is not ("not a subscription, not an MMO") than what it is.

It would be safer and perhaps wiser for No Man's Sky to skip the hype cycle in the wake of the game's launch, during which Murray became a poster child for promises gone undelivered---almost a spiritual successor to Peter Molyneux. After that rocky release, Murray and his team decided not to move straight to their next project but instead to stick with No Man's Sky, delivering upon all of their launch promises and much, much more. He maintains that the core fantasy of exploring a new planet was there from the get-go, but the game didn't look or run quite was well as it did in trailers and plenty of fans said they didn't get what they expected.

"When it launched I think two things really motivated us," he said. "One was that we could see people were playing. The general narrative is that they weren't, that it's a dead game, which is so common, but the numbers for us were still very impressive. The average play time was 25 hours at launch across many millions of people." He said some were playing for just an hour and bailing, others for hundreds.

Murray: "I made bad decisions at times for sure but it really hurt me for the team to have that legacy. They worked so hard."

The other motivation was to improve the reputation of the team. "The narrative around the game---for all of these games that comes out and act as a lightning rod---is that the team, they were lazy or they made bad decisions or they were dishonest or something like that." He laughed. "I made bad decisions at times for sure but it really hurt me for the team to have that legacy. They worked so hard." For most of the game's development, he said, there were only about six developers on it, somehow putting out this huge game.

These days there are fewer skeptics and more fans of Hello Games, more people appreciative of a team that has proven to be dedicated to improving their work and meeting those original expectations of the game's hype-heated launch.

The team at Hello has grown to about 25 people, Murray estimates. They're split across No Man's Sky, a different mystery project, and a smaller game called The Last Campfire that Murray hopes will help some of his developers experience the scrappy learning process a smaller Hello Games had when building 2010's motorcycle stunt game Joe Danger. He believes that experience gave Hello's early developers the skills to make the grander No Man's Sky. "We're losing that in the studio if we don't keep doing that sort of thing," he said of making the smaller games. "I don't want a load of people who haven't had that experience."

The Hello team is also relishing the positivity emerging from their big hit. They keep an internal website, Murray said, "where we put all the nice things and the way the game has impacted people." They hear from people who say the game is meditative and helps them relax. "And so you get a lot of people say it's helped them through tough times." They hear from fans who've logged 3,000 hours or more and need help fixing their save files or even building a new one. "I don't want to encourage this as a service we provide but we've done things where people will tell us, 'I had this, this and this on a save and I've played so long and I've lost it for whatever reason.' They broke up with their partner or whatever and we'll just do some debug things to try to rebuild some part of it."

"I didn't think it was a game you would actually play for a thousand hours," he said. "Two years out, people still care. People still want to sit down and talk about it and play it. That's a big deal for me. That's a nice thing for that team."