It's no secret that Apple and other multinational corporations have found countless loopholes to avoid paying taxes in the United States. Offshore accounts and subsidiaries in tax havens like Ireland and the Caribbean have become the favorite among tax savvy executives looking to help their bottom line. Government regulation in this area is also a bit of a gray line with what effectively amounts to an honor system of self-assessment. Everyone knows it happens, but there hasn't been much change.

A new Bloomberg report follows the global journey Apple's profits take. Products developed in California are sold worldwide, with most of the overseas profits, around $216 billion, being stashed in a subsidiary in Cork, Ireland. A financial haven for corporations seeking to avoid paying US taxes, 9 of the top 10 wealthiest US companies have subsidiaries based in Ireland. This topic has been well publicized, but the article goes on to further outline what Apple does with these earnings.

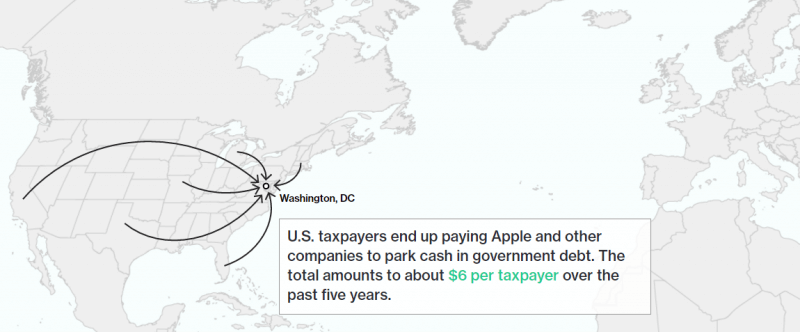

Braeburn Capital, is Apple's owned Reno, Nevada-based investment firm that manages the company's money and has been increasingly buying US treasuries. These treasury investments are then held and controlled by New York banks. The US Government has an obligation to pay interest on these purchases, which has done to the tune of $600 million in the past few years. Bloomberg estimates this total amounts to around $6 per US taxpayer over the last five years.

Ethics aside, Apple clearly knows what they are doing and has a very efficient machine set up to manage their finances. In short, University of Michigan law professor Reuven Avi-Yonah described it as paying someone to borrow a bike that you already own.

Image credit: Bloomberg

The strategy sounds like the plot from a financial themed movie drama, but it's not all that bad. Interest rates are low so this maneuver isn't currently a big money maker for Apple. They are effectively buying US debt which helps to finance government spending. In addition, the interest earned from buying this debt is also taxable.

In the wake of the 2016 election, the issue of what to do about offshore corporate accounts has come up again. Donald Trump has promised to help bring back some of the $2.6 trillion held overseas with a repatriation tax of 10%. It won't be easy and companies will do all they can to avoid paying any more than they have to, but this has historically been an issue both Democrats and Republicans can agree on.