AMD's Fall

There is no single event responsible for ousting AMD from its lofty position in early 2006. The company's decline is inextricably linked to its own mismanagement, some bad predictions, its own success, as well as the fortunes and misdeeds of Intel. The last factor seems a good place to start.

The Netburst architecture Intel employed with ever-decreasing effect gave way to a major design shift emphasizing low power and less reliance on high clock speeds for performance – a change that many deemed an overreaction to Netburst's shortcomings.

Regardless of the reasoning, Intel scratched plans and turned to its older Pentium Pro/Pentium M CPU architecture to build a successor for the Pentium 4. The initiative resulted in Intel's Conroe architecture (and every other since). Intel's move to a mobile-based chip design wound up being ideally suited to evolving markets. Overnight, AMD went from king of the hill to king of the foothill.

The other side of this particular coin is that AMD was the victim of its own success. While Intel was busy marketing the Core 2 Duo and its new 965/975X chipsets, AMD had to try selling AM2 socket boards to owners of the already superlative Socket 939. The fact that the newer components were only marginally better than those they were succeeding did little to support AMD's profit line.

Intel's move to a mobile-based chip design wound up being ideally suited to evolving markets. Overnight, AMD went from king of the hill to king of the foothill.

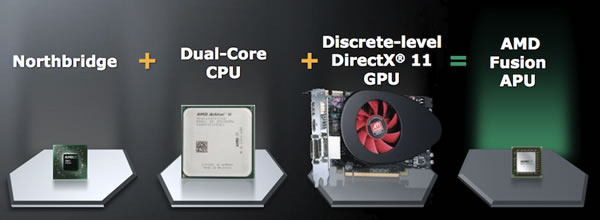

Three days before Intel launched Conroe, AMD managed to sucker punch itself. On July 24, 2006, AMD announced that it intended to acquire ATI in a deal worth $5.4 billion, comprising $4.3 billion in cash and $1.1 billion raised from 58 million shares. The deal was a huge financial gamble, representing 50% of AMD's market capitalization at the time, and while the purchase made sense, the price did not.

ATI was grossly overvalued, a conclusion AMD eventually acknowledged when it absorbed $2.65 billion in write-downs due to overestimating ATI's goodwill valuation. To compound the lack of management foresight, Imageon, the handheld graphics division of ATI, was sold for relative peanuts to Qualcomm in a $65 million deal (now named Adreno, an anagram of "Radeon" and an integral component of the Snapdragon SoC), while Xilleon, a 32-bit SoC for Digital TV and TV cable boxes, was sold to Broadcom for $192.8 million.

On the day that AMD announced the finalized acquisition of ATI, October 25, 2006, the company also formally unveiled its Fusion initiative, which took over five years to hit shelves as Brazos and Llano – a fine example of the product delays that have troubled AMD since moving on from K6-K8.

Two weeks after Conroe's (Core 2 Duo) launch, AMD's CEO Dirk Meyer announced the finalization of AMD's quad-core Barcelona PROCESSOR. But instead of stealing Intel's thunder, the party officially halted with the discovery of a bug that in rare circumstances could result in lockups when involving nested cache writes. Rare or not, the TLB bug put a stop to AMD's K10 production, while in the meantime a BIOS patch that cured the problem on outgoing processors would do so at the expense of ~10% performance. By the time the revised 'B3 stepping' CPUs shipped, the damage had been done, both for sales and reputation.

A conscious effort to abstain from advertising and a near total absence from the software side of the business makes for a curious example of how to deliberately handicap yourself in the semiconductor trade.

Interwoven with AMD's woes, especially of late, have been slow transitions to smaller process nodes, partially to gain the maximum return on investment for each successive process tooling. The poor execution of GlobalFoundries (previously AMD's manufacturing foundry division which was sold in March 2009) initiated a slow and problematic ramp of the 32nm process and caused an interminable delay in getting Llano and Bulldozer parts to market in quantity – notably the top parts of both lineups (the A8-3850 and FX-8150).

No review of this era in AMD's history would be complete without taking into consideration Intel's nefarious deeds. At this juncture, AMD was not only fighting Intel's chips, but also the company's monopolistic activities, which included paying OEMs large sums of money – billions in total – to actively keep AMD CPUs out of new computers.

In the first quarter of 2007, Intel paid Dell $723 million to remain the sole provider of its processors and chipsets (accounting for 76% of the system builder's total operating income of $949 million). AMD would later win a $1.25 billion settlement in the matter, which is surprisingly low on the surface, but probably exacerbated by the fact that at the time of Intel's shenanigans, AMD itself couldn't supply enough CPUs to its existing customers.

The last seemingly ever-present factor in AMD's decline pertains to management, or the lack thereof. A conscious effort to abstain from advertising and a near total absence from the software side of the business makes for a curious example of how to deliberately handicap yourself in the semiconductor trade. This, allied with an enduring lack of strategic planning and an apathetic (at best) leadership seem to be the abiding portrait of a company run as a conglomeration of fiefdoms.

So, if AMD had managed to avoid all those pitfalls, would it be in a dominant position today? No. Not only would AMD have needed to execute perfectly, but they would have also required significant slippage in Intel's own product cycles, which has not happened.

Unlike AMD, Intel has rigid long-term goal setting, greater product and IP diversity, huge budgets for marketing, R&D, and software, as well as foundries tailored to its products and timetable.

Intel's business philosophy seems to guard against that eventuality. Unlike AMD, Intel has rigid long-term goal setting, greater product and IP diversity, huge budgets for marketing, R&D, and software, as well as foundries tailored to its products and timetable. Those factors would have ensured AMD struggled for market share.

That doesn't mean that AMD couldn't have flourished compared to its current position. The $2.5 billion overpayment for ATI (and the attendant loan interest) could have undoubtedly been better allocated, not least of which would have been increased R&D funding to improve products and hasten their release. Such decisions would have also placed AMD in a stronger bargaining position with Intel over the antitrust settlement, instead of settling for Intel's lowball $1.25 billion offer to service debts falling due.