In context: This past decade or so has been one of significant technological advancement, across several different industries. We've seen the rise of the modern smartphone (and tablets alongside it), a new generation of gaming consoles, medical AI innovations, and increasingly efficient and powerful computer hardware. Now, we're seeing another major leap forward in the optical lens industry, thanks to a breakthrough discovered by a team of Harvard SEAS researchers.

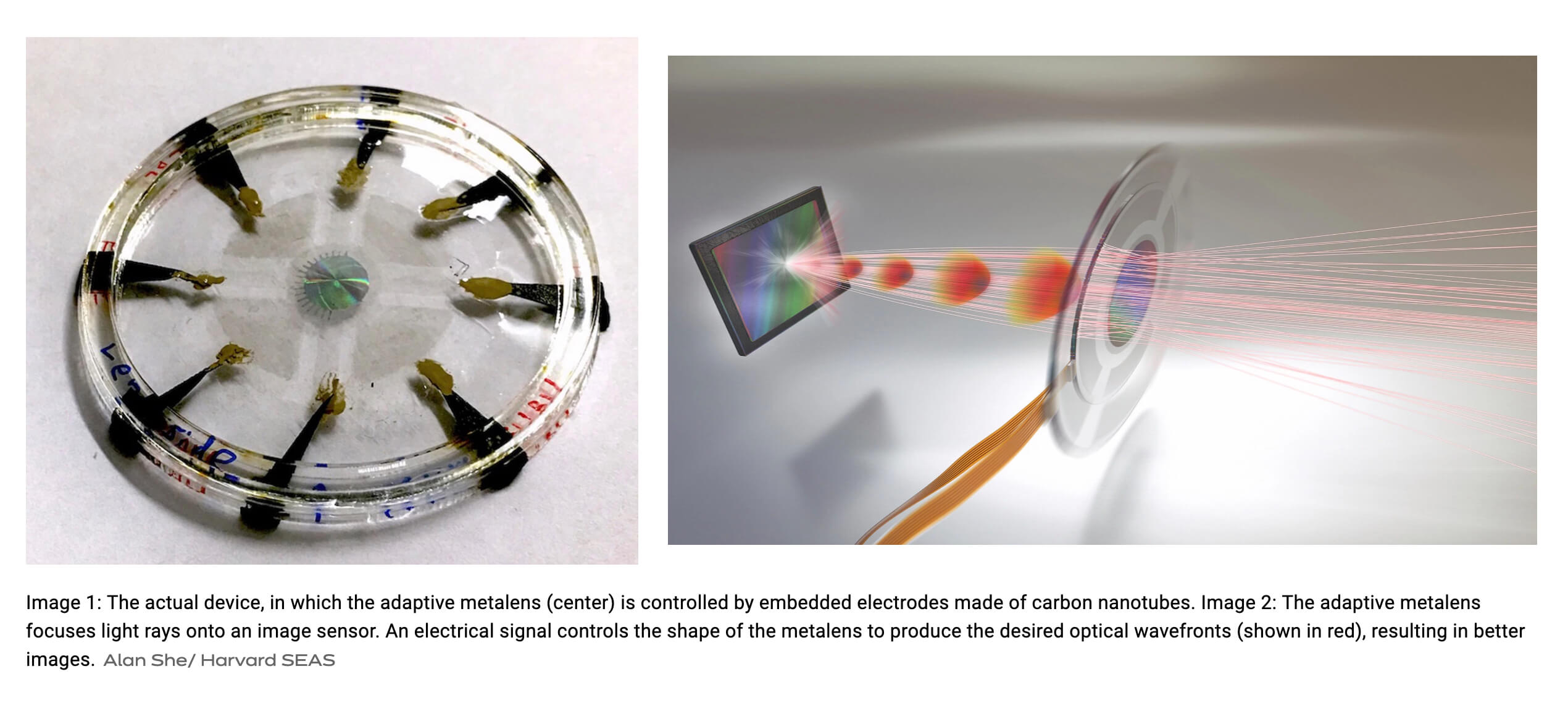

The team in question has developed an "adaptive metalens," that can adjust its focus in real-time, as the human eye can – but with some added improvements that allow it to outperform what even the best human eyes are capable of.

The metalens, according to researcher Alan She, can not only change its focus, but it can also dynamically correct for "aberrations" such as astigmatism (a condition that causes blurred vision) and "image shift." As you can imagine, such a lens would be tremendously useful for consumers: it could be built-in to high-tech eyewear, installed in cameras, or used in microscopes.

Apparently, researchers have managed to combine two industries: semiconductor manufacturing and lens-making. "This research provides the possibility of unifying two industries, semiconductor manufacturing and lens-making," said researcher Federico Capasso. "whereby the same technology used to make computer chips will be used to make metasurface-based optical components, such as lenses."

"This research provides the possibility of unifying two industries, semiconductor manufacturing and lens-making, whereby the same technology used to make computer chips will be used to make metasurface-based optical components, such as lenses."

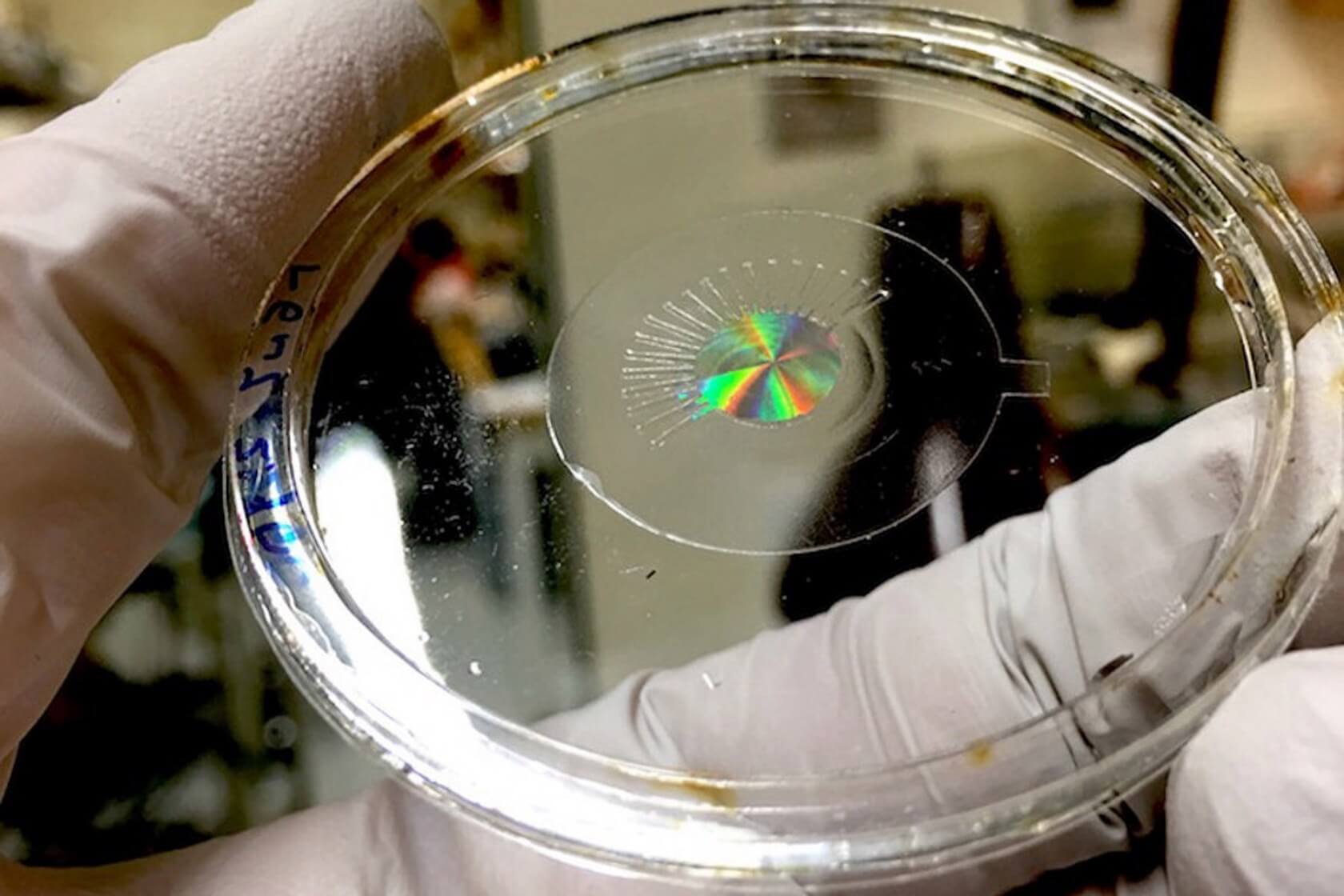

The team's metalens is comprised of many tiny "nanostructures," embedded electrodes, and dielectric "elastomers" (artificial muscles), which can shrink or stretch based on the voltage applied to them. The idea was to emulate a healthy human eye, which uses surrounding ciliary muscle to change the shape of its "lens," and then build upon it.

Combined, the metalens and its corresponding elastomers only come in at about 30 microns thick, but they can be up to several millimeters (or more) in diameter. Compared to the research team's previous metalens projects (which only resulted in lenses about the size of a piece of glitter) this new lens could prove far more efficient and practical for consumer gadgets and eyewear.