In a nutshell: A team of Stanford Medicine researchers has developed a new blood test that can estimate the biological age of major organs, shedding light on why some people age faster than others and offering a powerful new tool for predicting disease risk and longevity. The findings suggest that the biological age of an individual's organs – especially the brain – may be a more accurate predictor of health outcomes than chronological age.

While most people mark their age by the number of birthdays they've celebrated, scientists have long known that the body's organs do not all age at the same rate. "We've developed a blood-based indicator of the age of your organs," said Tony Wyss-Coray, professor of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford and senior author of the study, which was published in Nature Medicine. This new indicator, he explained, allows researchers to "assess the age of an organ today and predict the odds of you getting a disease associated with that organ 10 years later."

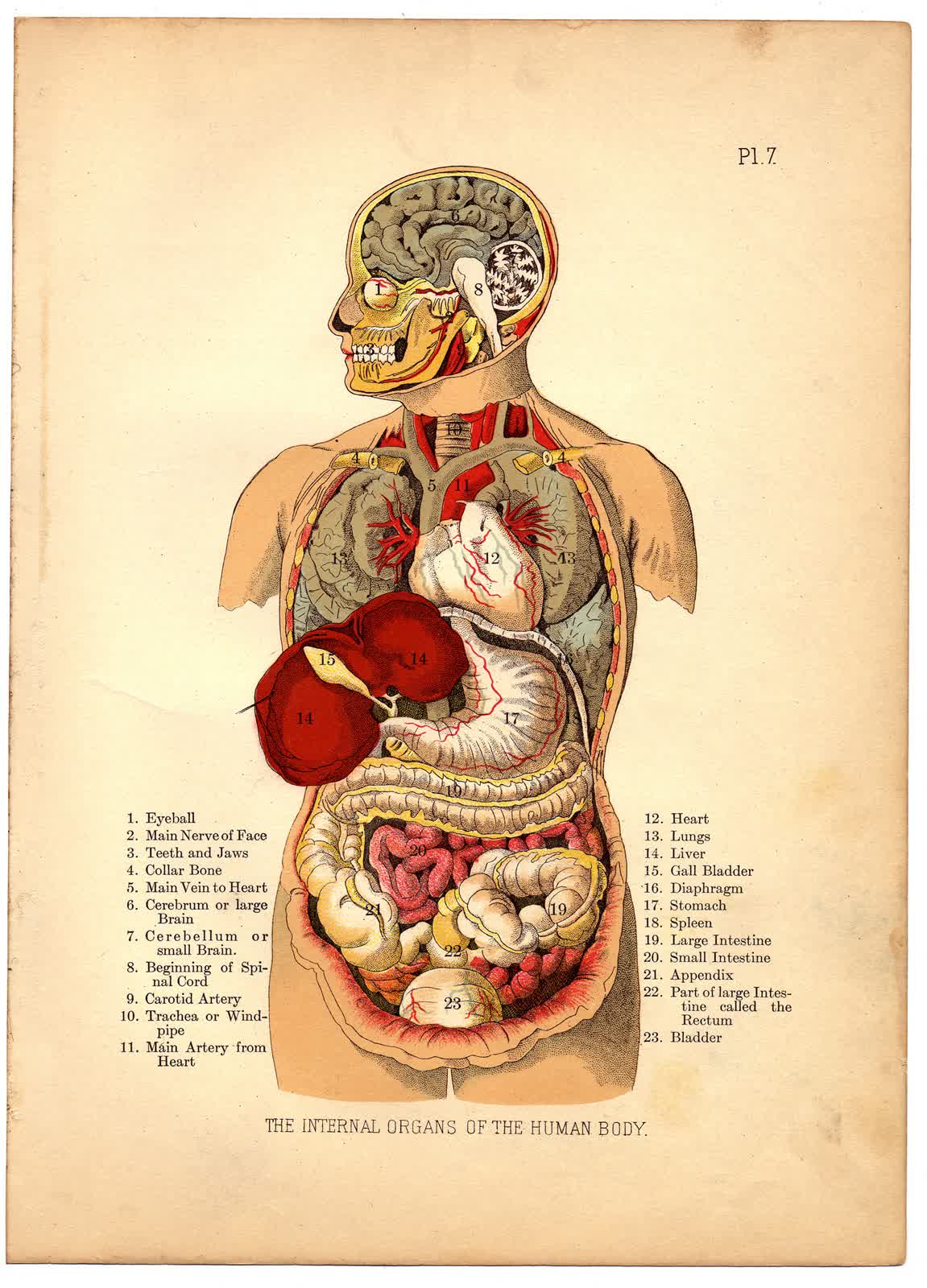

The research team analyzed blood samples from 44,498 participants, aged 40 to 70, enrolled in the UK Biobank, a large-scale biomedical database. Using a laboratory technology capable of measuring nearly 3,000 proteins in the blood, the scientists focused on proteins linked to 11 organ systems: brain, muscle, heart, lung, arteries, liver, kidneys, pancreas, immune system, intestine, and fat.

By comparing each person's protein levels to age-adjusted averages, the researchers developed an algorithm that assigns a biological age to each organ system. If an organ's protein signature deviated by more than 1.5 standard deviations from the average, it was classified as "extremely aged" or "extremely youthful." About one-third of participants had at least one organ in these extreme categories, and one in four had multiple organs that were either especially old or young.

The study found that the biological age of specific organs strongly predicted the risk of developing diseases associated with those organs. For instance, an "extremely aged" heart increased the likelihood of atrial fibrillation or heart failure, while aged lungs predicted a higher risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The most striking results came from the brain: people with an extremely aged brain were 3.1 times more likely to develop Alzheimer's disease than those with a normally aging brain. Conversely, those with an extremely youthful brain had only about a quarter of the risk.

"The brain is the gatekeeper of longevity. If you've got an old brain, you have an increased likelihood of mortality," Wyss-Coray said. "If you've got a young brain, you're probably going to live longer." The data showed that an extremely aged brain increased the risk of death by 182% over 15 years, while an extremely youthful brain reduced the risk by 40%.

The ability to estimate the biological age of organs could transform how doctors approach aging and disease. "This approach could lead to human experiments testing new longevity interventions for their effects on the biological ages of individual organs in individual people," Wyss-Coray said. He envisions a future where doctors intervene before symptoms appear, using organ age as an early warning system.

The test is currently available for research purposes, but Wyss-Coray, who is a co-founder of two biotechnology companies, hopes to commercialize it within the next few years. He believes that as the technology improves and focuses on key organs like the brain, heart, and immune system, the cost will decrease and the test's predictive power will increase.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Milky Way Foundation, the Knight Initiative for Brain Resilience, and the Stanford Alzheimer's Disease Research Center. As research continues, scientists hope to use organ-age assessments to better understand how lifestyle, diet, and medications influence aging – and to develop new strategies for keeping organs youthful and healthy for longer.