Editor's take: Researchers have figured out a way to take pictures with the ambient light sensors on most mobile devices and laptops. The study has spawned more than a few fear-mongers and clickbait headlines. While the findings are fascinating and prove a potential for abuse by bad actors, its viability as an attack vector is severely limited using current technology.

Researchers at MIT's Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) have developed a method of capturing images using only the ambient light sensor found on most mobile devices and many laptops. The study "Imaging Privacy Threats From an Ambient Light Sensor" suggests a potential security threat since, unlike the selfie camera, there are no settings to turn off the component. Apps also do not have to gain a user's permission to use them.

"People are aware of selfie cameras on laptops and tablets and sometimes use physical blockers to cover them," says CSAIL PhD student Yang Liu, who co-authored the research article published in January's Science Advances. "But for the ambient light sensor, people don't even know that an app is using that data at all. And this sensor is always on."

Typically, not many apps use the light sensor as it only provides data about how much light reaches it, which limits its usefulness. Its primary function is to provide ambient light data to the operating system for automatic screen brightness adjustment, but it does have an API. So developers can access and use it. For example, the app could use the API to turn on a low-light mode. The camera apps on most devices do this.

Capturing an image is much more complicated since it is essentially a single pixel sensor with no lens measuring luminance at about five "frames" per second. To overcome this disability, the researchers sacrificed temporal resolution for spatial resolution, which allowed them to reconstruct a single image from minimal data.

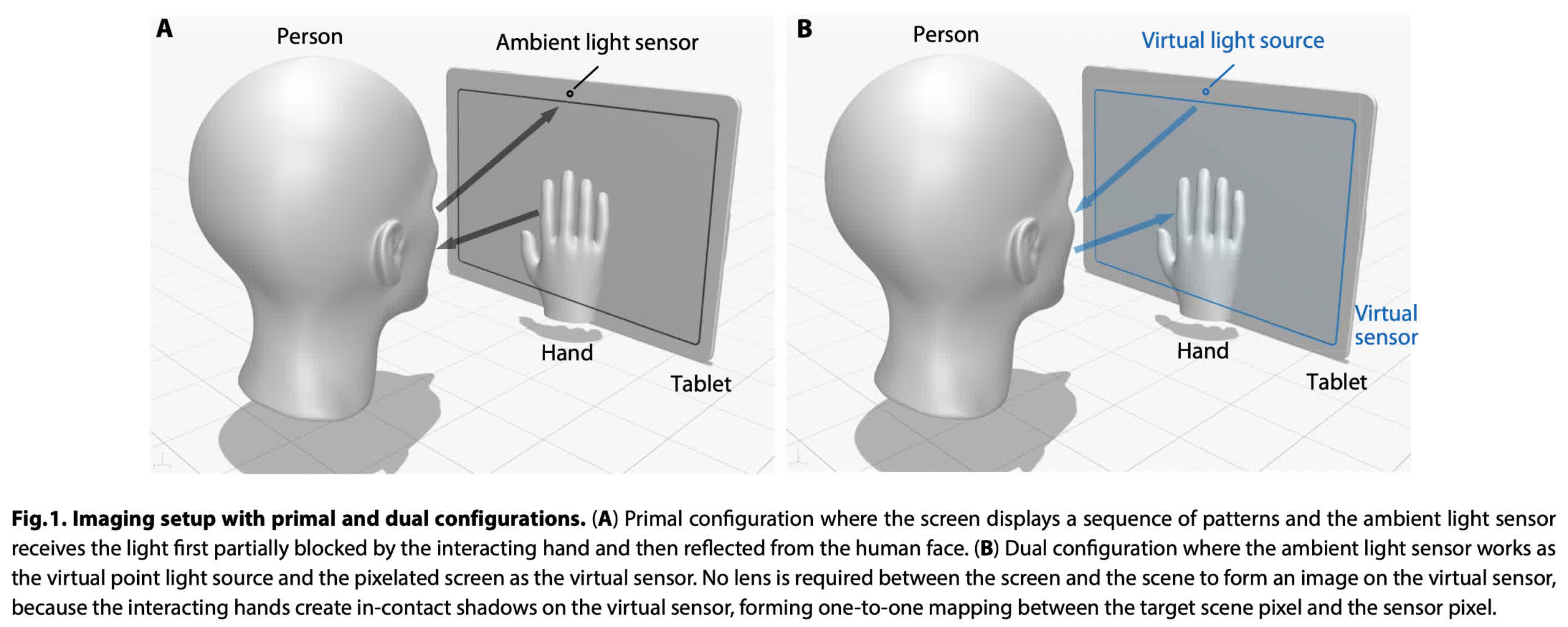

The process uses a physics principle called Helmholtz reciprocity. This concept states that the reflections, refractions, and absorptions experienced in a light ray's path are the same if the ray took the same route in reverse. Simply put, computer algorithms reverse the sensor data (inversion) to create an image from the light source's (display's) point of view, e.g., a shadow above the screen.

The researchers demonstrated this using a new, unmodified Samsung Galaxy View2 tablet with a 17-inch display. They placed the tablet before a mannequin head and used cardboard cutouts and actual human hands to simulate gestures.

Lighting has to be specific for the trick to work reliably. Remember, the algorithms use reverse path tracing from the sensor to the light source, which is the display. So, the researchers had to light specific portions of the screen to get a readable image. Since this would create a very unusual behavior that a user could find suspicious, they also replicated the process using a modified Tom and Jerry cartoon to achieve the proper illumination patterns.

This dual photography method created low-resolution images (32x32) that were clear enough to show gestures like two-finger scrolling or three-finger pinching. Because of the minimal resolution, the technique only works with larger displays like tablets and laptops. Mobile phone screens are far too small.

Its biggest drawback is its speed. The sensor can only record one pixel at a time, so it takes 1024 passes (less than five per second) to create one 32x32 image. Practically speaking, this means it takes 3.3 minutes to generate an image using a static black-and-white pattern. Using the modified video method takes 68 minutes.

Fortunately for consumers, this level of sluggishness is too "cumbersome" to be an attractive attack vector for hackers. Waiting three minutes to an hour to process one image is far too inefficient for the method to be useful for anything more than a proof of concept. Attackers would need an exponentially faster sensor for this method to be viable enough to gain beneficial information.

"The acquisition time in minutes is too cumbersome to launch simple and general privacy attacks on a mass scale," independent security researcher and consultant Lukasz Olejnik told IEEE Spectrum. "However, I would not rule out the significance of targeted collections for tailored operations against chosen targets."

Even still, without a way to capture several hand positions in short succession, it would be impossible to gain anything useful, like a PIN or password.