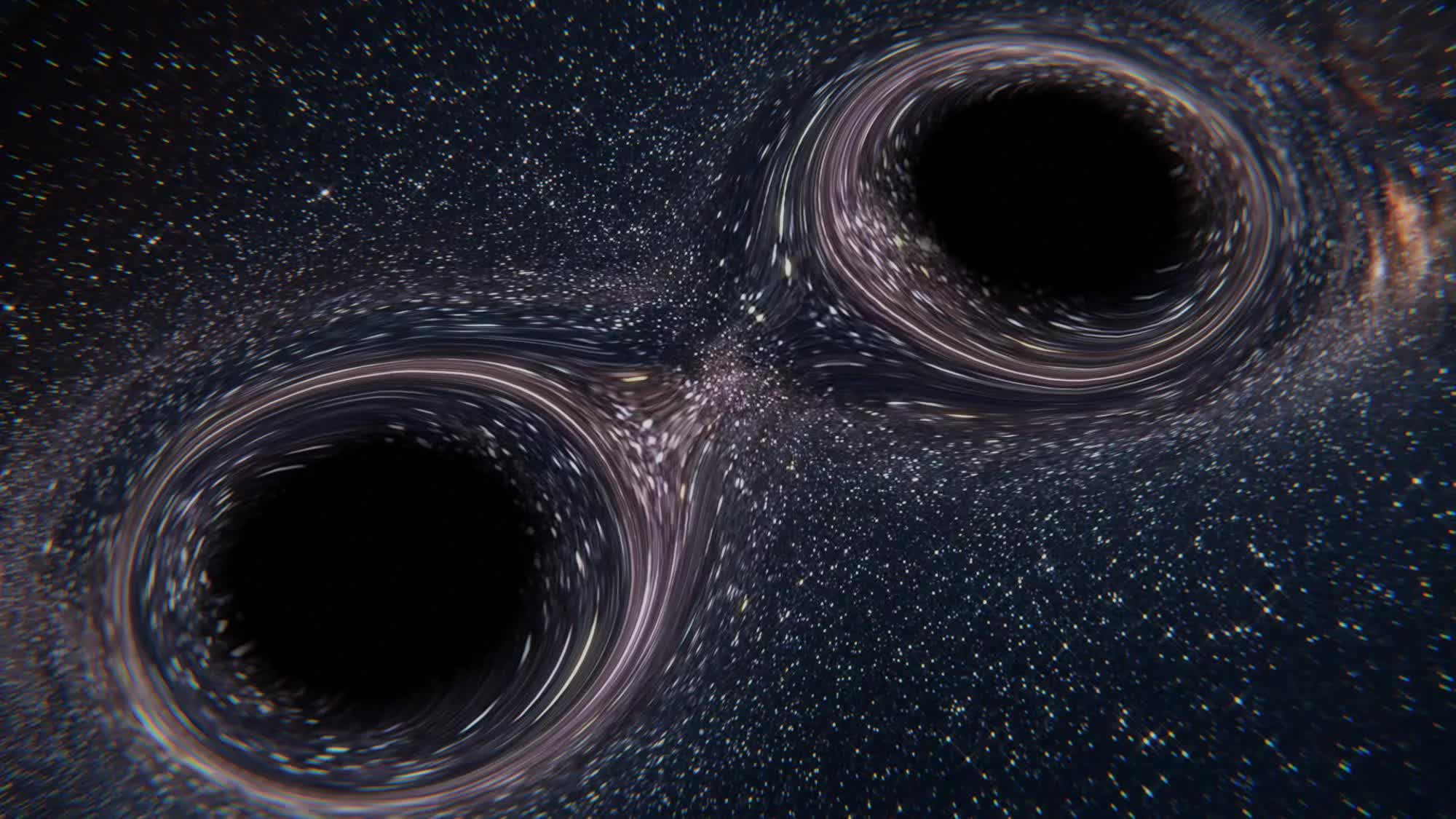

What just happened? A few years after making history with the first detection of gravitational waves, LIGO has observed a new, unprecedented cosmic event: the most massive black hole merger ever recorded. This extraordinary discovery challenges existing models of physics and astrophysics, prompting scientists to launch long-term investigations into the newly captured data.

The LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK) collaboration has announced a groundbreaking discovery in the field of gravitational wave astronomy. The international research team has detected the most massive merger of two distinct black holes ever recorded. The event, designated GW231123, resulted in the formation of a new black hole with a mass 225 times that of the Sun.

The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) first made history in 2016 when it confirmed the existence of gravitational waves, providing strong evidence for Einstein's general theory of relativity. Gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of space-time that travel at the speed of light and can only be detected using instruments of extreme precision, such as those operated by LIGO.

Originally funded by the National Science Foundation and operated by Caltech and MIT, LIGO now works in tandem with two additional observatories: Virgo in Italy and KAGRA in Japan. These detectors form the LVK collaboration. Their latest observing run, conducted in November 2023, led to the detection of GW231123.

The two black holes involved in GW231123 had estimated masses of approximately 100 and 140 times that of the Sun, making them the most massive ever detected in LIGO's history. Before this event, the record-holder was GW190521 – discovered in 2021 – with a combined mass of 140 solar masses.

What makes GW231123 even more extraordinary is that both black holes were rapidly spinning, near the theoretical limits imposed by Einstein's general relativity. According to LVK researcher Charlie Hoy, such high rotational speeds shouldn't be possible under standard models of stellar evolution, making the discovery difficult to explain with current astrophysical theories.

One leading hypothesis is that these black holes themselves originated from earlier mergers. In this scenario, smaller black holes formed a binary system that eventually merged again, resulting in the enormous and fast-spinning pair seen in GW231123.

LVK member Gregorio Carullo notes that it may take years for scientists to fully unravel the implications of this event. The findings are being officially presented at the 24th International Conference on General Relativity and Gravitation in Glasgow, Scotland.