Forward-looking: Although precision medicine has advanced rapidly in recent years, many cancer patients still undergo standard treatments that may not work for everyone. Research underway on the International Space Station offers a glimpse of future care, where doctors map out each course of therapy using a detailed simulation of the patient's cancer.

In a laboratory more than 249 miles above Earth, a new generation of cancer research is unfolding. A biotech startup is harnessing the microgravity environment of the International Space Station to study how real patient tumors grow and respond to anti-cancer drugs – work that may one day lead to more precise, personalized treatments on Earth.

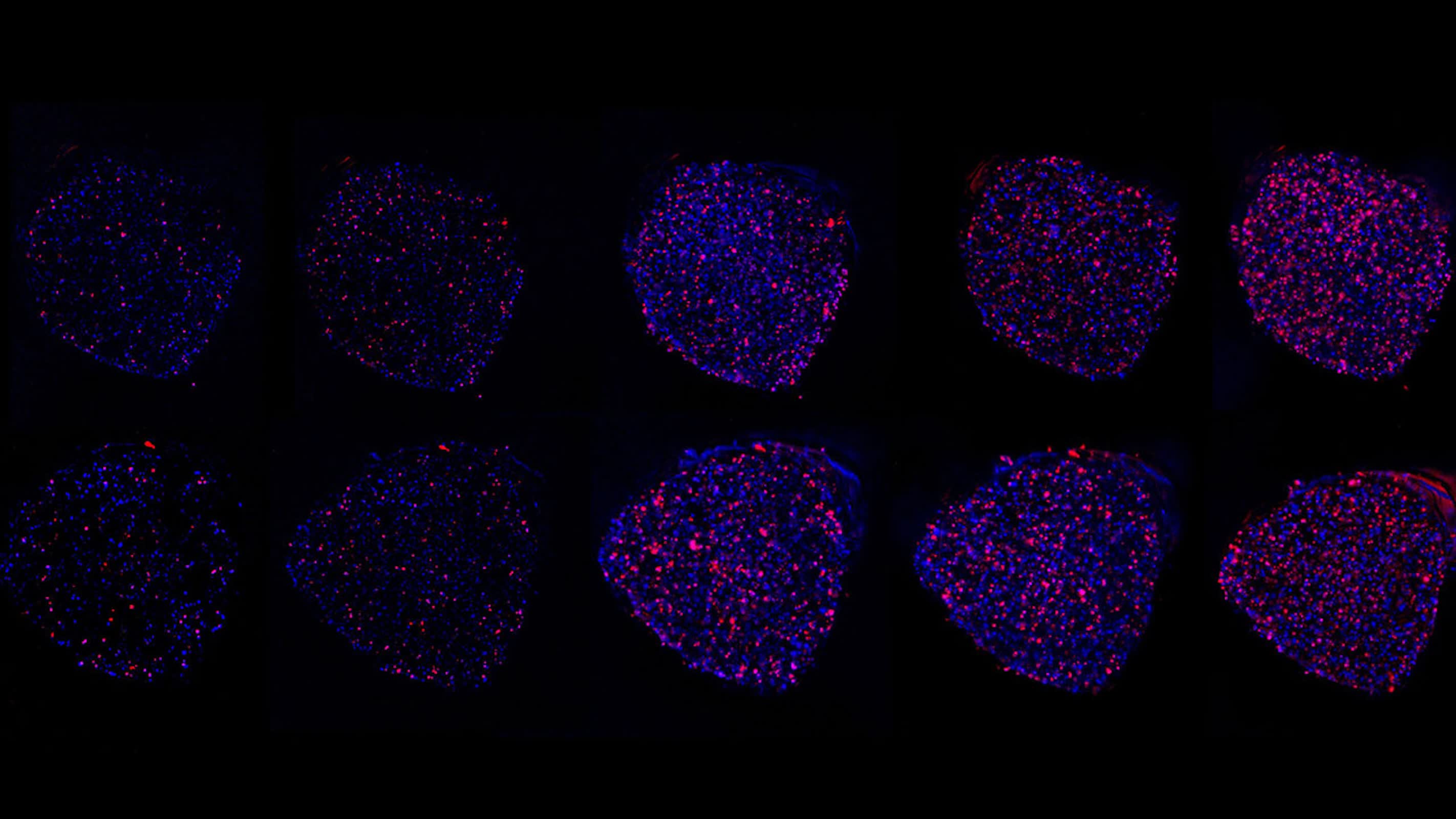

At the heart of this effort is a system developed by Encapsulate, a biotechnology company founded by cancer researchers. Their technology allows living tumor samples, collected from patient biopsies, to be grown into small, three-dimensional tumors. Unlike conventional cell cultures, these microtumors mimic the complexity of human cancer more closely, especially in the unique conditions of space.

Microgravity – the near-weightless state experienced in orbit – changes how cells interact and organize. On Earth, gravity pulls cells downward, often limiting how they assemble in a petri dish. But in space, tumors can develop in ways that scientists say may better reflect how they behave in the human body. The Encapsulate team is using the ISS's stable microgravity environment as a laboratory, sending their tumor-on-a-chip devices to orbit in small, self-sustaining labs and monitoring them remotely.

Part of NASA's In Space Production Applications program, Encapsulate's research recently gained new momentum through substantial grants. The company received $3.63 million from NASA and another $1.25 million from the US National Science Foundation. These investments are fueling both technical development and a larger clinical study in partnership with multiple prominent cancer centers in the United States.

The clinical study, now underway, brings together UConn Health, Moffitt Cancer Center, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and other medical institutions. The research will use Encapsulate's chips to analyze tumor tissue from up to 200 patients with colorectal and pancreatic cancers. The hope is that by observing tumors' reactions to chemotherapy in orbit, the study can highlight which drugs work best for each patient.

Early results have been promising, according to researchers involved. The experiments have revealed that tumors may behave differently in space than on Earth, sometimes responding to treatments with reactions not seen in ground-based labs. These differences hint at possible new markers for predicting how cancers might spread or resist certain drugs.

Encapsulate's system is fully automated for use in space, requiring only minimal action from astronauts – essentially plugging in a pre-programmed device. Investigators on the ground then monitor the miniature tumors' growth and drug response, gathering data that could change how clinical oncologists approach treatment choices.

Partners in the clinical trials say the ultimate goal is to eliminate much of the guesswork in selecting cancer therapies. By testing patient-derived tumors in a realistic three-dimensional model before administering any drugs to the patient, clinicians could avoid ineffective treatments and move more quickly to options tailored for each case.