Why it matters: Hospitals have a constant need for donated blood. Approximately 30,000 units per day are used to treat accident victims and people with blood ailments like sickle cell anemia. Hospitals often suffer shortages when they receive a high number of trauma patients. But what if we could duplicate a typical donation in a lab and give it a longer shelf life?

National Health Service (NHS) scientists in the United Kingdom, with help from Bristol and Cambridge universities, have successfully transfused two humans with blood grown in a lab. The BBC notes that this world's first is part of a continuing study to determine how lab-grown blood performs in the body.

As of Monday's announcement, both subjects have had no ill effects. It is worth noting that for safety, only a small amount of blood is transfused in these trials (about one or two teaspoons). The testing will continue with eight more healthy volunteers.

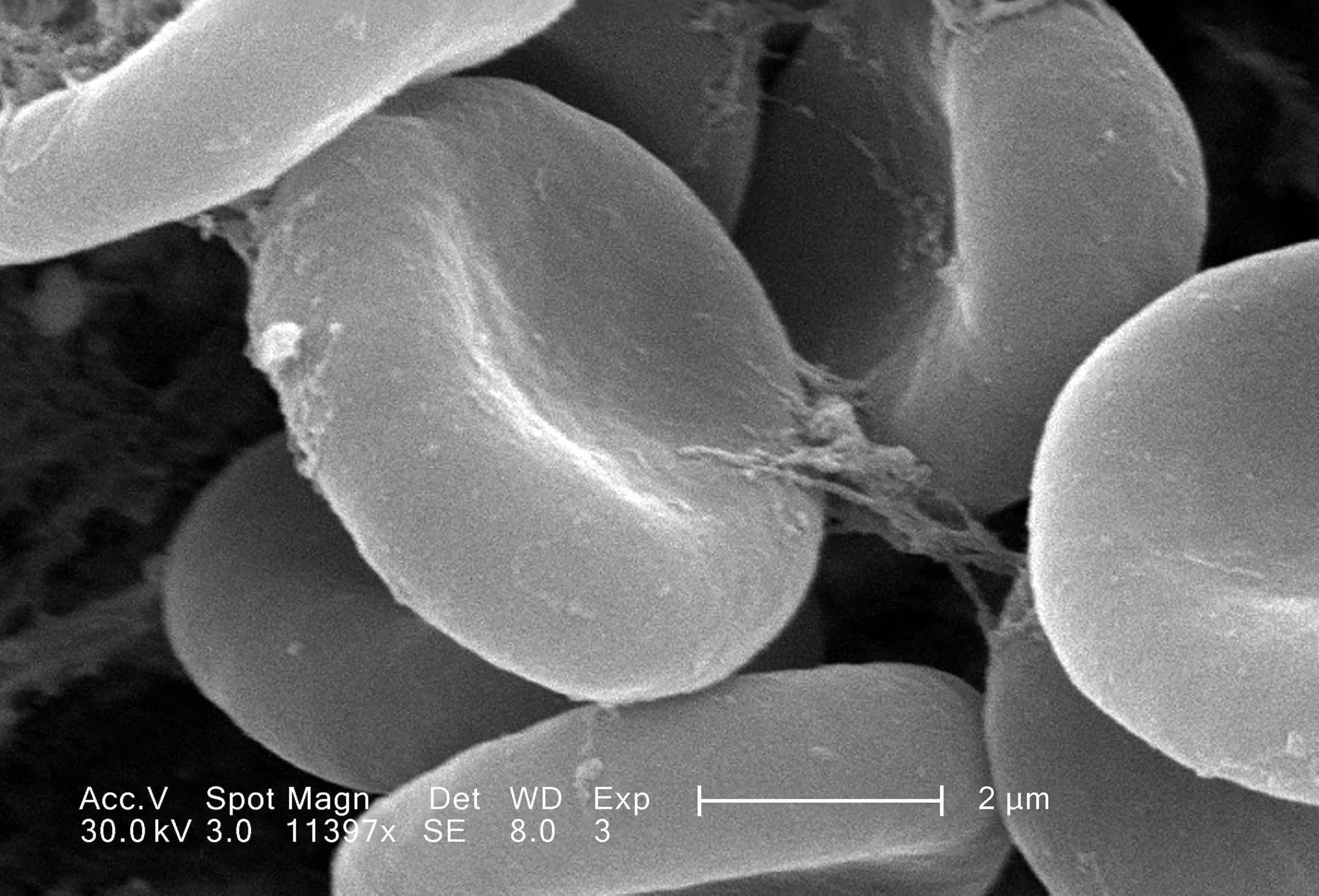

The synthesized blood cells are produced by isolating stem cells in a regular pint of blood using magnetic beads. The scientists "guide" a sample of about 500,000 stem cells to produce 50 billion red blood cells. That sample is then filtered to harvest only the ones suitable for transfusing (about 15 billion cells).

The scientists hope to accomplish a couple of things. The main goal is to have the ability the synthesize and supplement hospitals, clinics, and blood banks with usable rare blood types. Type AB-negative is the rarest ABO type, with only one percent of the population having it. More importantly, people with O-negative are known as universal donors because their blood is compatible with all types. However, only seven percent of the population has O-negative, so it is in high demand.

There are even rarer types, such as Hh, also known as the Bombay blood group. This type only occurs in 0.0004 percent of the world's population (0.01 percent in Mumbai, where it was discovered). Like O-negative, anyone can receive Hh without complications, but people in this group are not compatible with any ABO types, including the universal O-negative, and must receive Hh blood.

"We want to make as much blood as possible in the future, so the vision in my head is a room full of machines producing it continually from a normal blood donation," University of Bristol Professor Ashley Toye told the BBC.

A secondary goal of the study is to see if synthesized blood has a longer "lifespan." Our bodies continually produce red blood cells. Typically, each lasts about 120 days. However, the shelf life in a blood bank is far shorter because cells of varying ages are all mixed. The thought is that since lab-grown blood is uniformly "young," it should theoretically last the full 120 days before needing to be replaced.

To track this theory, the researchers inject subjects with a normal sample and and then a synthetic at least four months later. Each is tagged with a radioactive isotope so they can tell how long each cell circulates in the bloodstream. If correct, the lab-grown blood should remain in the test subject longer.

If the trials are successful, blood banks and hospitals should have far fewer shortages of needed blood types, but the technology does have a substantial cost. Regular donations cost around £130 ($150 US) to collect, bag, and store. Producing it in a lab is "vastly" more expensive, although the researchers were tight-lipped about precise figures.

There are also some limitations in how many stem cells clinicians can harvest. Regardless of the expense and obstacles, the researchers are optimistic about the benefits of their work.

"This world-leading research lays the groundwork for the manufacture of red blood cells that can safely be used to transfuse people with disorders like sickle cell," said NHS Blood and Transplant Medical Director of Transfusion Dr. Farrukh Shah. "The potential for this work to benefit hard to transfuse patients is very significant."