In brief: Researchers at University College London (UCL) and Cambridge discovered a new form of ice. It is not naturally created on Earth but may exist on the icy moons of gas giants. It is just one of 23 types of H2O ice scientists have discovered and has properties that fundamentally change our understanding of water's "solid" state.

Although water is a fundamental building block of life and covers over 70 percent of Earth's surface, it has many anomalous properties that even modern science has not reconciled. For example, under immense pressure, water becomes easier to compress. This property is inverse to any other substance.

"Water is the foundation of all life," said University College London (UCL) Chemistry Professor Christoph Salzmann. "Our existence depends on it, we launch space missions searching for it, yet from a scientific point of view it is poorly understood."

After all, another strange property of water is that as it cools, it becomes dense. This increased density causes cold water to sink below its warmer molecules. Both of these characteristics are normal. However, water reaches peak density at only 4 degrees Centigrade, just above freezing. Then as it nears 0C and begins to form ice crystals, it becomes less dense and rises, which is why ice floats. This trait is unique to water, which is why scientists are so interested in its solid forms.

The study of water's solid phase has led to scientists discovering over 20 types of ice. There are 20 crystalline forms and two amorphous types --- high-density (HDA) and low-density (LDA). Scientists discovered LDA in the 1930s when they exposed water vapor to a steel sheet chilled to -100C. Fifty years later, they found they could create HDA by compressing ice at nearly -200C.

Both of these forms of water are found in space because there is not enough thermal activity to form crystalline ice. The closest they exist on Earth is in the upper atmosphere. The gap in density suggests there should be a middle ground, but scientific consensus chalked it up to just another weird property of water.

"There is a huge density gap between [high-density and low-density amorphous ice], and the accepted wisdom has been that no ice exists within that density gap," said Salzmann.

However, Salzmann, Dr Alexander Rosu-Finsen, and a team of other scientists from UCL and Cambridge created a new form of amorphous ice in the lab that resides in the gap between HDA and LDA. They call it "medium-density amorphous ice," or MDA.

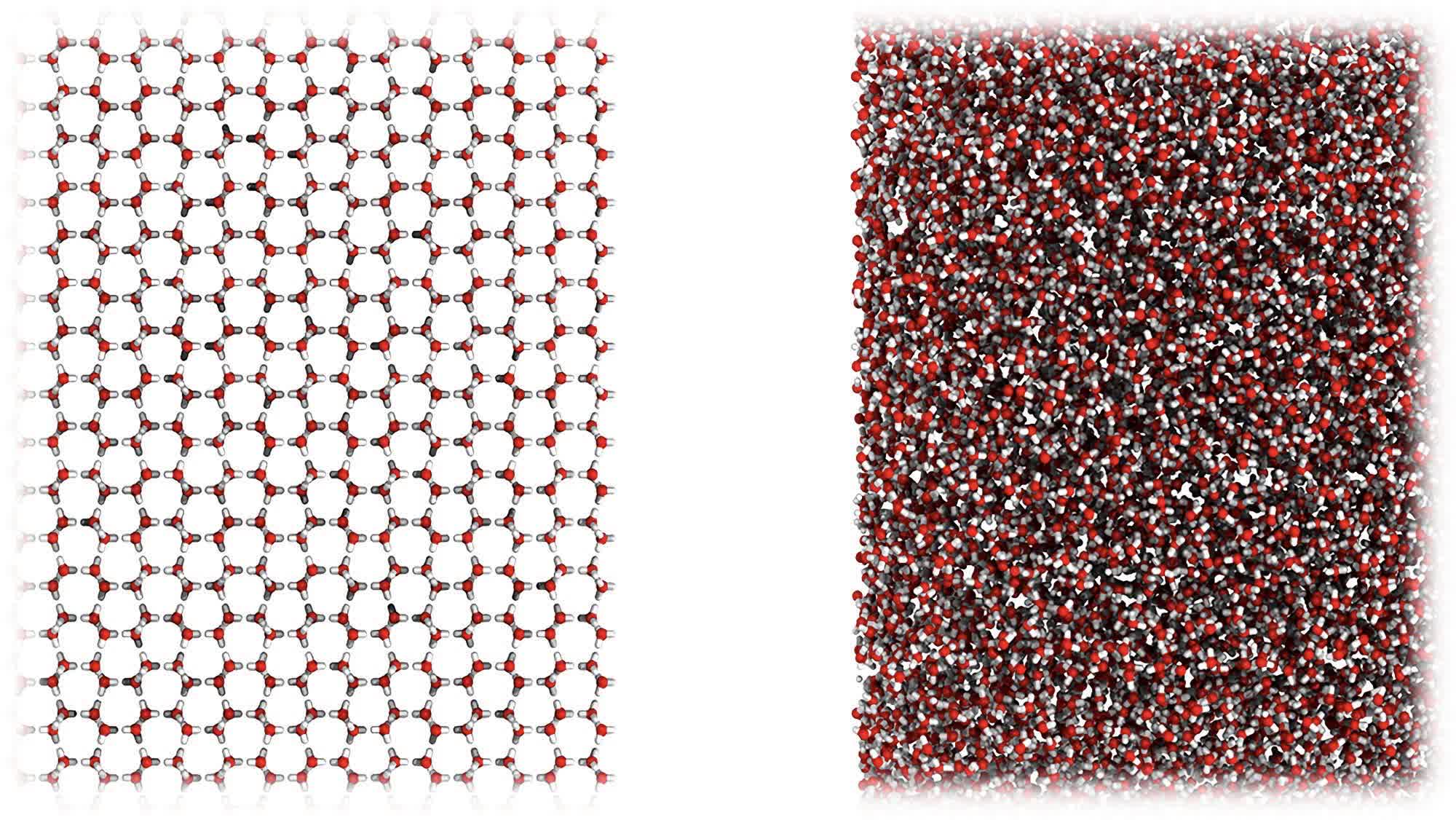

The researchers found it somewhat accidentally when they put regular ice through a ball milling process at -200C just to see what would happen (above). The result was an entirely new H2O phase that looks more like water than ice at the molecular level (below). The white powdery substance will move to the touch, like water, but is dense enough to hold its shape, like ice. It actually has the same density as water without being liquid.

Dr Rosu-Finsen explains that the ball milling process pulverized the ice crystals, transforming them into an amorphous mass.

"We shook the ice like crazy for a long time and destroyed the crystal structure," he said. "Rather than ending up with smaller pieces of ice, we realized that we had come up with an entirely new kind of thing, with some remarkable properties."

Co-author of the study, Professor Andrea Sella, added, "We have shown it is possible to create what looks like a stop-motion kind of water. This is an unexpected and quite amazing finding."

One of the more interesting anomalous properties of MDA is that as it "thaws," it reforms into crystalline ice --- a process that releases an "extraordinary" amount of heat. The researchers theorize that this could be what causes "icequakes" on Jupiter's moon Ganymede.

The team published its research in the February 2 issue of Science. The MDA discovery will undoubtedly lead to more study of this peculiar form of ice.