In brief: NASA has developed a pair of fixes designed to ensure its Voyager probes continue operating in interstellar space for as long as possible. One issue the team targeted involves the thrusters on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, which are used to help keep the craft's antennas pointed at Earth.

As propellant flows, it passes through inlet tubes that are 25 times narrower than external fuel lines. Over decades, propellant residue has gradually accumulated within the narrow tubes, reaching a noticeable level.

To slow the rate of buildup, NASA has started letting each spacecraft rotate slightly more – about one degree farther in each direction – than in the past. They're also performing fewer, longer thruster firings that should prolong the crafts' lifespan.

"This far into the mission, the engineering team is being faced with a lot of challenges for which we just don't have a playbook," said Linda Spilker, project scientist for the mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. "But they continue to come up with creative solutions."

It's unclear exactly when the inlet tubes will become too clogged to function, but NASA believes it shouldn't happen for at least another five years and possibly much longer.

NASA is also working a separate issue involving an unusual bug on Voyager. In 2022, Voyager 1's onboard computer started sending back garbled status reports. Months of debugging pointed to an issue with the attitude articulation and control system (AACS), which was writing commands into memory instead of processing them.

NASA determined that the AACS had found its way into an incorrect mode, but wasn't sure what caused it or if it could happen again. To give the Voyager mission the best chance of continued success, NASA developed a software patch that should prevent the issue from resurfacing.

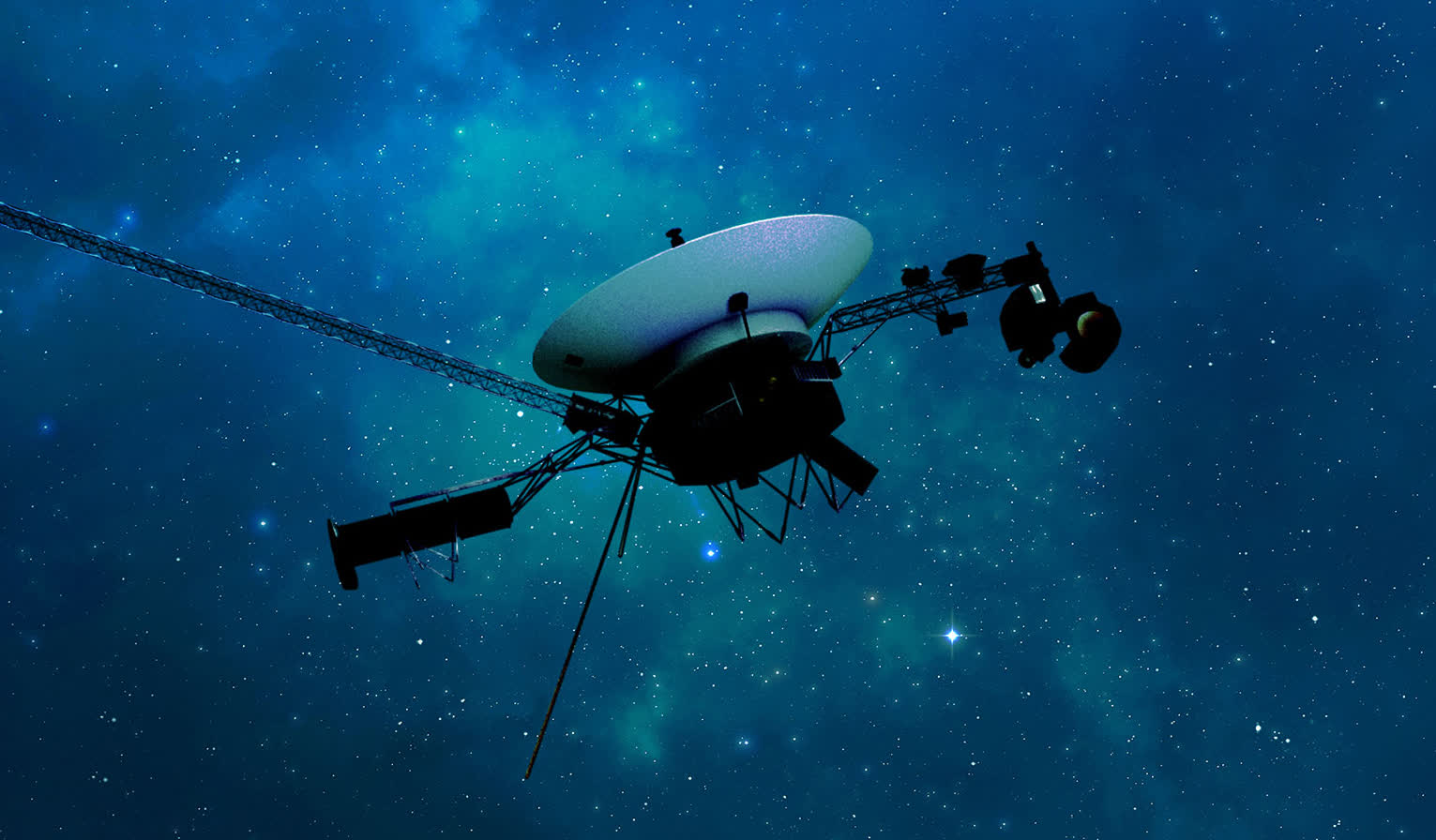

NASA's Voyager 2 probe launched in 1977 along with its twin, Voyager 1. The craft took off 16 days before Voyager 1 and was originally commissioned as a five year mission to study Jupiter and Saturn. The probe eventually conducted flybys of Uranus and Neptune, entered interstellar space in 2018 (Voyager 1 did so in 2012), and is still providing useful data all these years later.