In context: New research reveals that South Africa's land is rising not due to deep-earth forces but because of severe water loss from droughts and groundwater depletion. This discovery presents a powerful new approach to monitoring water scarcity and informing resource management in an era of growing climate uncertainty.

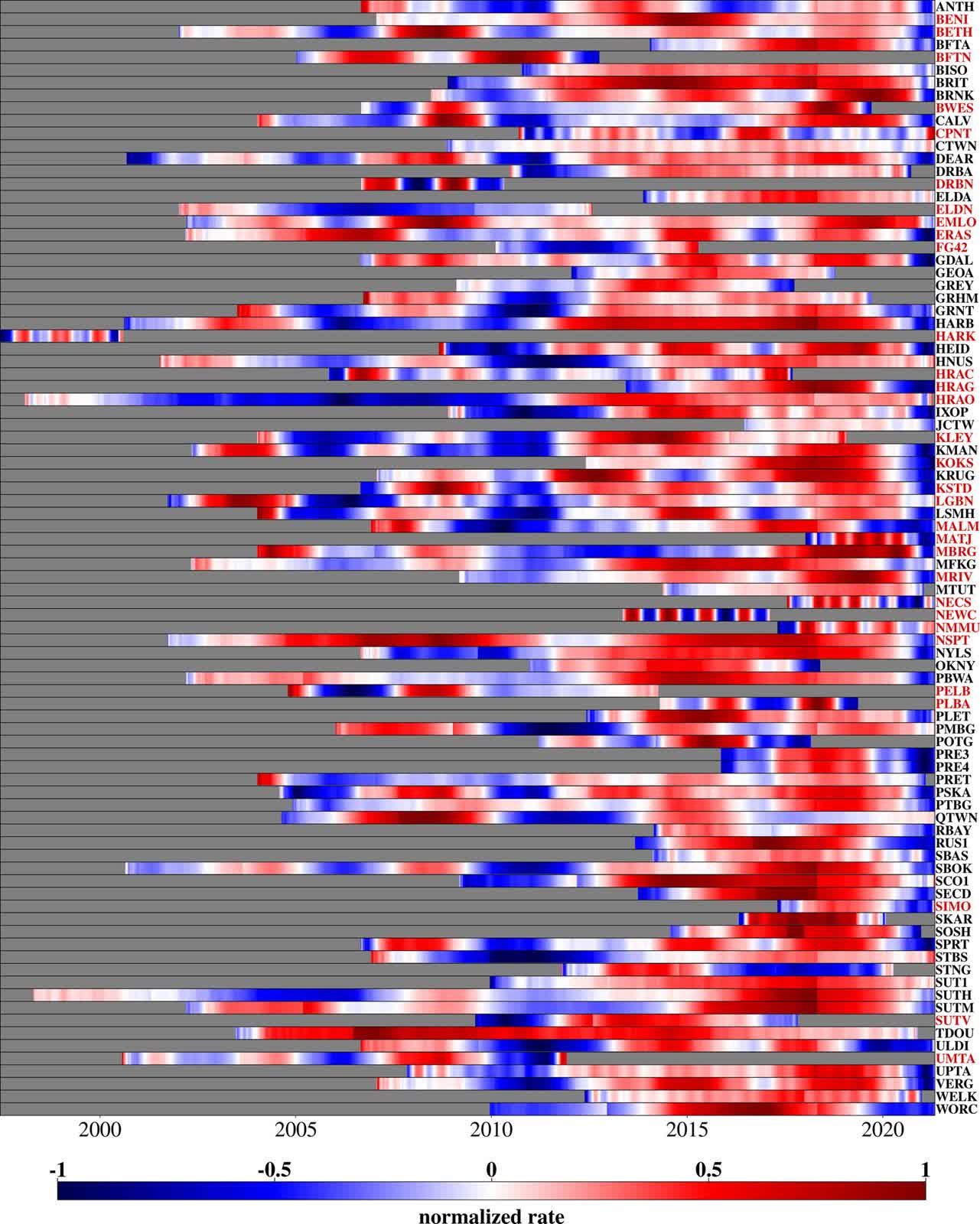

Over the past decade, parts of South Africa have risen by as much as six millimeters – a subtle but measurable shift detected by a network of high-precision Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) receivers. These instruments, which track millimeter-scale changes, revealed a pattern that overturns long-held geological assumptions: vanishing groundwater, not ancient tectonic forces, is pushing the land upward.

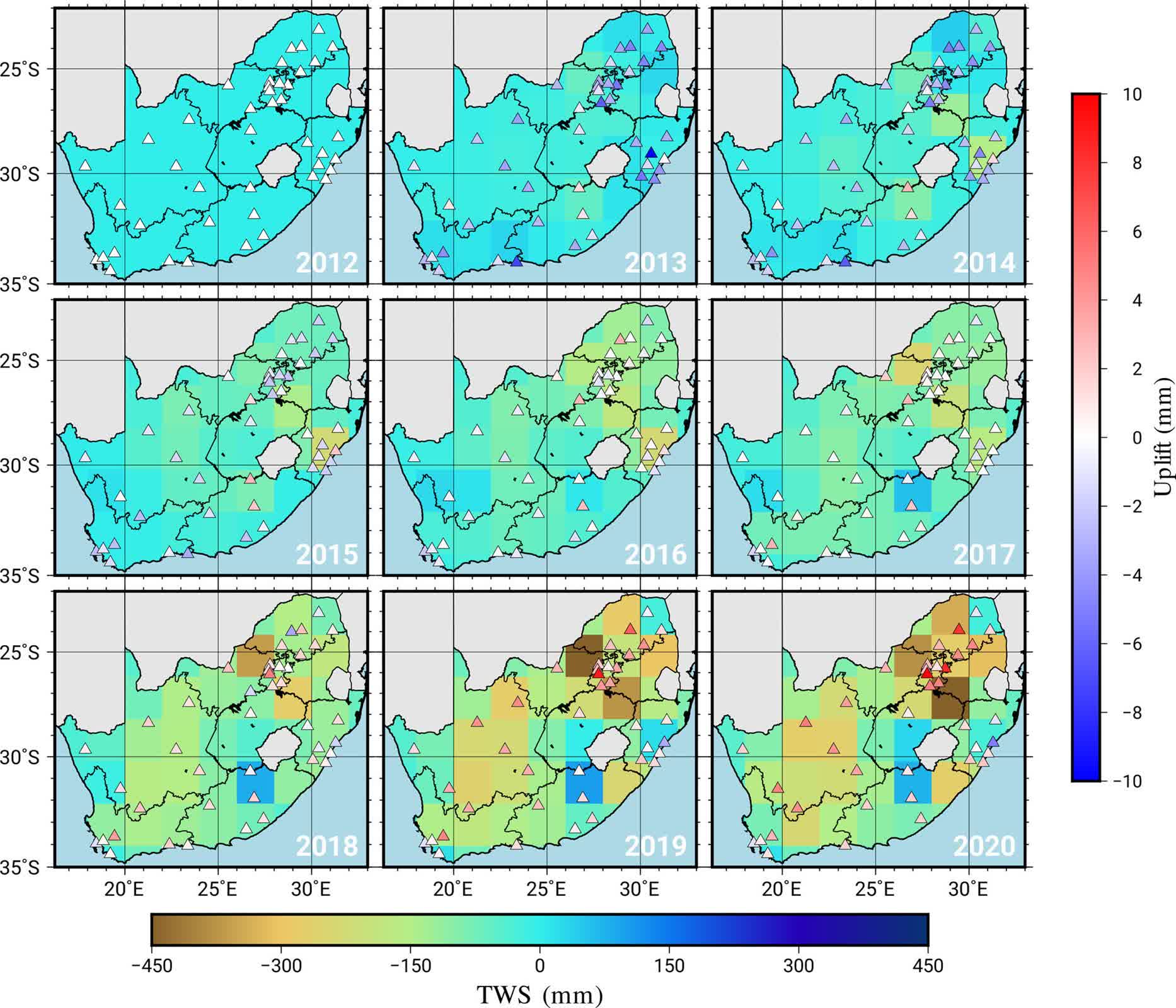

For years, scientists linked the phenomenon to mantle plumes – columns of molten rock rising from deep within Earth. However, a collaborative study led by the University of Bonn's Dr. Makan Karegar, Christian Mielke, Dr. Helena Gerdener, and Dr. Jürgen Kusche tells a different story. The researchers found a direct correlation between severe droughts and land uplift by combining GNSS data with satellite measurements from NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE). Areas that suffered the worst water losses showed the most pronounced elevations.

While revolutionary for mapping large-scale water mass changes, the University of Bonn notes that the GRACE satellites offered only coarse regional snapshots with resolutions spanning hundreds of kilometers. Researchers turned to hydrological models that simulated water cycles at far finer scales to fill the gaps. These models confirmed what field data suggested: as reservoirs emptied, soils parched, and groundwater dwindled, the Earth's crust rebounded like a foam ball released from a clenched fist.

These models confirmed what field data suggested: as reservoirs emptied, soils parched, and groundwater dwindled, the Earth's crust rebounded – like a foam ball released from a clenched fist. This elastic response isn't merely academic. Nearly half of South Africa's freshwater reserves lie underground, tapped relentlessly for agriculture, industry, and drinking water.

The 2015-2019 drought, which brought Cape Town to the brink of "Day Zero" – when taps would have run dry – exposed the fragility of these reserves. Now, the same GNSS stations that detected the uplift could become early-warning systems, as scientists can estimate groundwater loss by measuring how the land lifts. This data could help guide decisions on when to ration water before crises strike.

The implications extend beyond national borders. As climate change disrupts rainfall patterns worldwide, this method provides a low-cost tool for monitoring groundwater in regions from California to the Indus Basin. South Africa's experience could serve as a prototype for water-stressed areas across the globe.