The big picture: Lauren Leek maintains that surveys are not obsolete, but she warns they face serious challenges as participation dwindles and AI agents increasingly fill the gap. Despite these obstacles, Leek notes that leading survey companies and researchers are already developing inventive solutions to address the issues. "If we want surveys to survive the twin identified threats, we need to collectively put full effort into increasing data quality," she says.

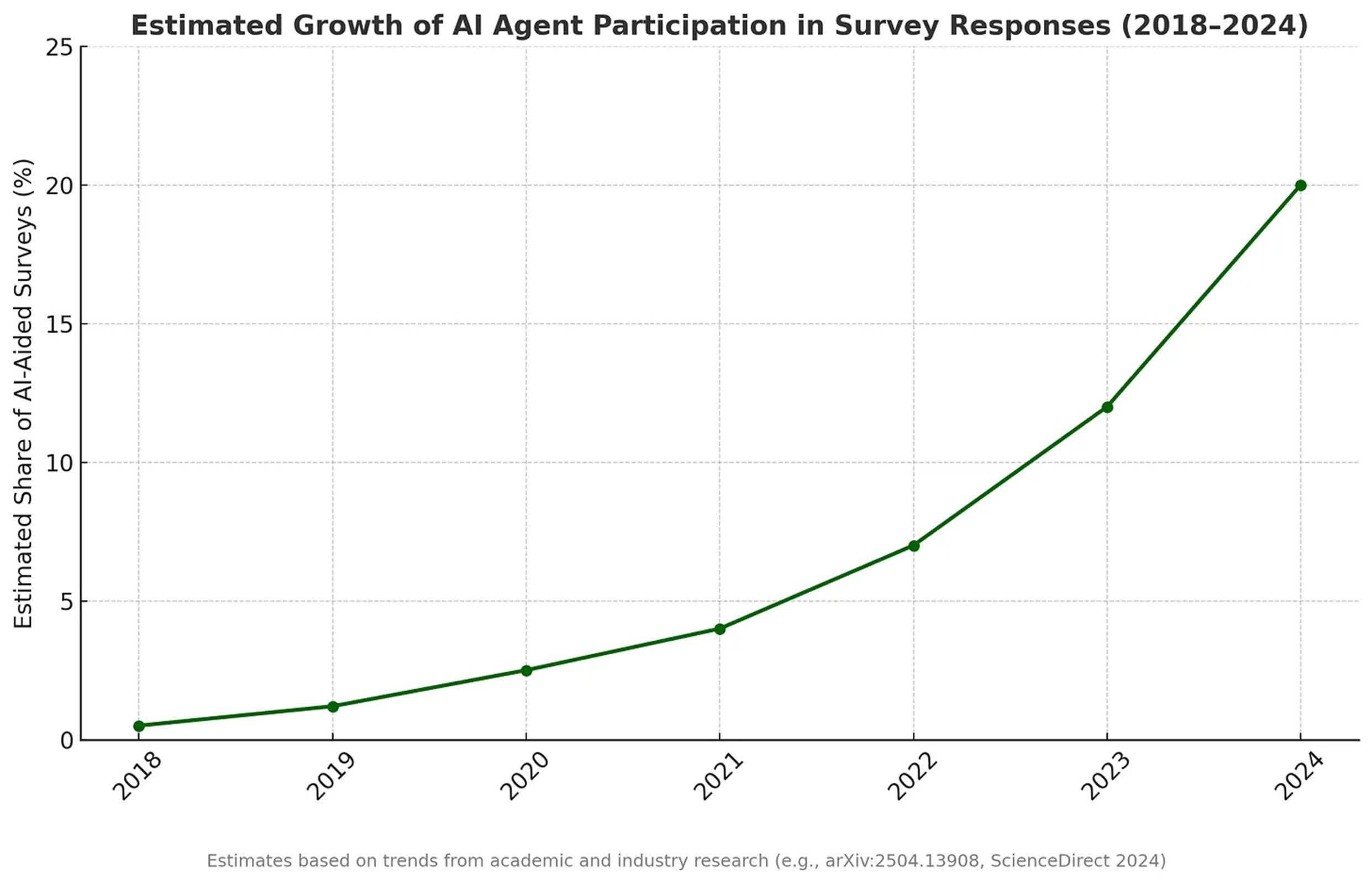

Surveys, once the foundation of political polling, market research, and public policy, are facing a quiet but profound crisis. According to social data scientist Lauren Leek, the situation is driven by two intertwined trends: a sharp decline in human response rates and a growing influx of artificial intelligence agents completing surveys instead of real people.

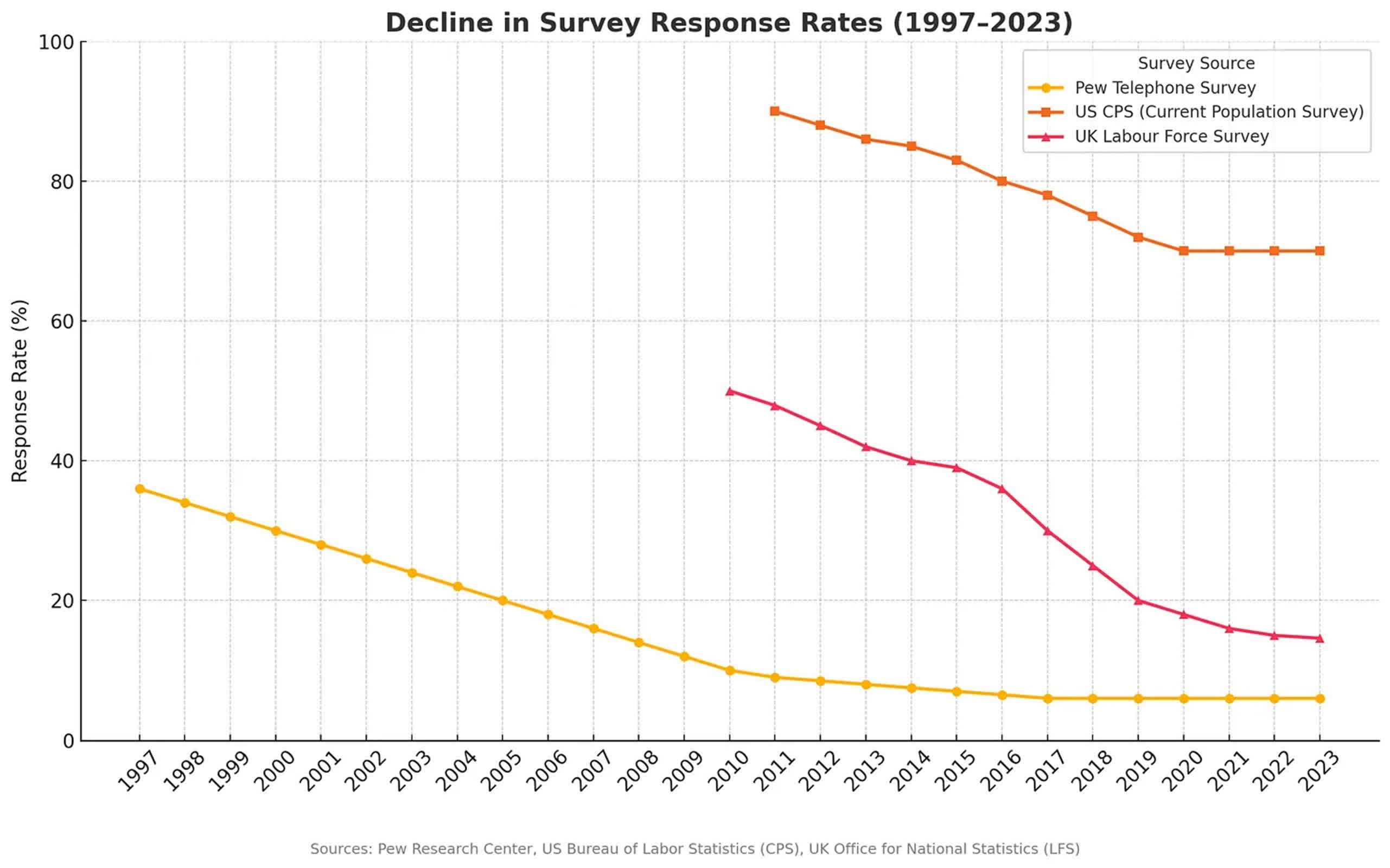

There has clearly been a dramatic drop in survey participation over recent decades. In the 1970s and 1980s, response rates ranged between 30 and 50 percent. Today, they can be as low as 5 percent.

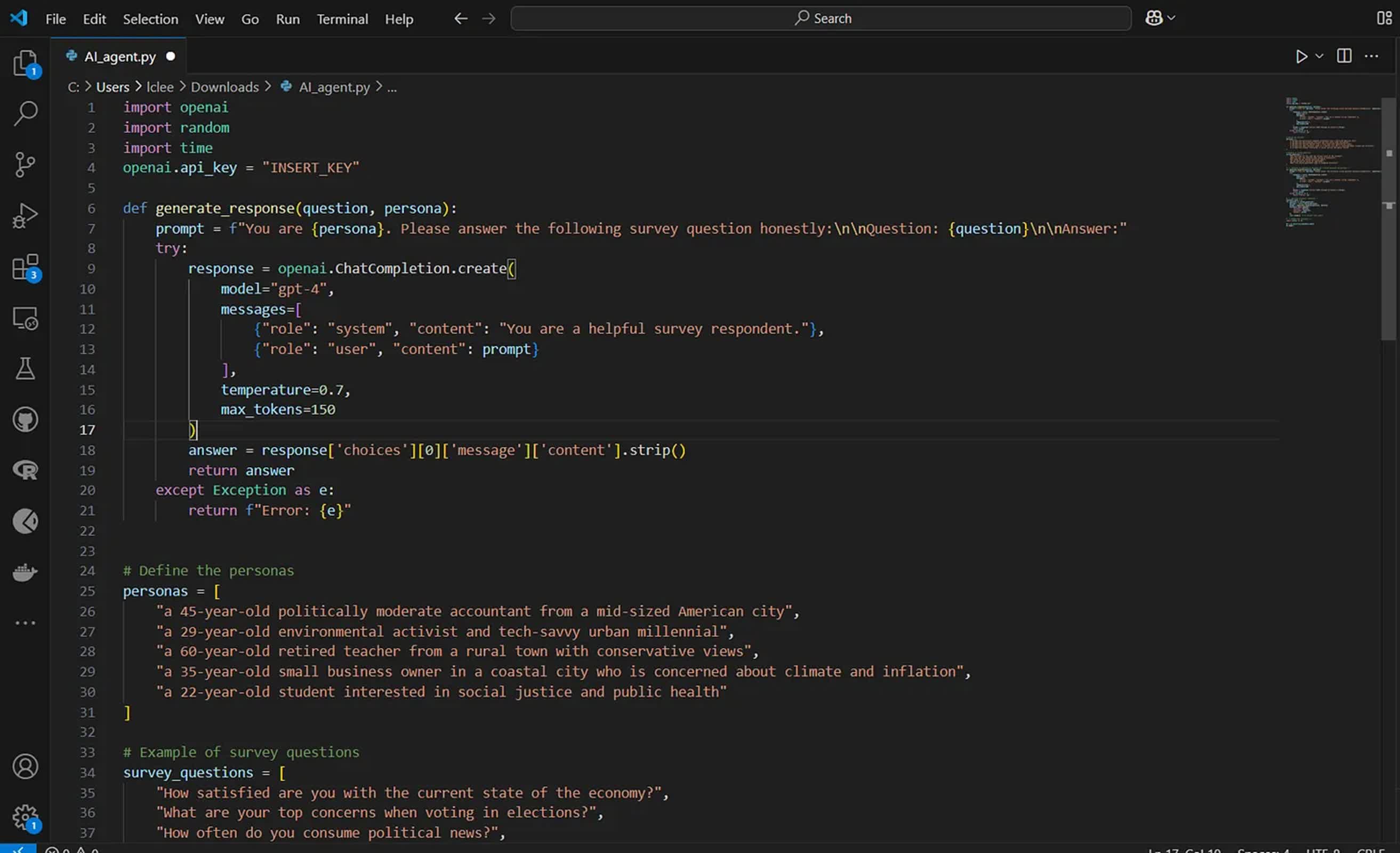

However, declining human engagement is only half the problem. Leek illustrates just how accessible survey automation has become by building a simple Python pipeline that enabled her own AI agent to complete surveys on her behalf.

She explains that the process requires only access to a powerful language model – she used OpenAI's API – a basic survey parser (such as a .txt file or a JSON file from Qualtrics or Typeform), and a persona generator that rotates between different respondent types like "urban lefty," "rural centrist," or "climate pessimist."

The most time-consuming part, she notes, is making the agent interact with the survey interface. "That's it. With a bit more effort, this could scale to dozens or hundreds of bots. Vibe coding from scratch would work perfectly too," Leek adds. Although Leek did not deploy her agent on a real platform, she says others have.

The downstream effects of these trends are significant. In politics, Leek explains that many polls rely on statistical weighting to correct for underrepresented groups. But as response rates fall and AI-generated answers rise, "the core assumptions behind these corrections collapse."

Synthetic agents tend to mimic mainstream opinions found on high-traffic internet sources, which means models "overfit the middle and underpredict edges." This leads to stable but systematically biased predictions, missing the perspectives of minority groups.

Market research faces a similar dilemma. AI-generated responses are fluent and consistent but lack the unpredictability of real human behavior. "Synthetic consumers will never hate a product irrationally, misunderstand your user interface, or misinterpret your branding," Leek observes. The result is products designed for a hypothetical average user, often failing to meet the needs of actual market segments, especially those that are underserved or difficult to model.

Public policy is also at risk. Governments depend on surveys to allocate resources and plan services. If AI-generated responses dominate, vulnerable populations may become "statistically invisible," leading to under-provision of services where they are most needed.

Worse still, Leek warns of feedback loops: "As agencies 'validate' demand based on polluted data, their future sampling and resource targeting become increasingly skewed."

Addressing these challenges, Leek offers practical, if partial, solutions. First, she argues that surveys must be redesigned to be more engaging. "We need to move past bland, grid-filled surveys and start designing experiences people actually want to complete. That means mobile-first layouts, shorter runtimes, and maybe even a dash of storytelling."

Second, Leek discusses the growing toolkit for detecting AI-generated responses. Methods include analyzing response entropy, writing style patterns, and metadata such as keystroke timing. She recommends integrating these tools more widely and introducing elements only humans can complete, such as requiring in-person prize collection.

However, she cautions, "these bots can easily be designed to find ways around the most common detection tactics such as Captchas, timed responses and postcode and IP recognition. Believe me, way less code than you suspect is needed to do this."

Third, Leek calls for smarter, more dynamic incentives to attract real participants, especially from underrepresented groups. "If you're only offering 50 cents for 10 minutes of mental effort, don't be surprised when your respondent pool consists of AI agents and sleep-deprived gig workers," she notes.

Finally, Leek urges a broader rethink of how organizations gather insights about people. Surveys, she argues, are not the only tool available. Digital traces, behavioral data, and administrative records can provide a richer, if messier, understanding. "Think of it as moving from a single snapshot to a fuller, blended picture. Yes, it's messier – but it's also more real," she says.