The big picture: Governments worldwide are employing several strategies to track the spread of Covid-19, and the US too has started using anonymized location data from mobile ads to get a clear picture of the pandemic's evolution. The pretext of using surveillance to plan an appropriate response to the virus has also raised some questions about the persistence of these measures once the situation is under control.

Earlier this month, there were reports that talked about the US government's intention to work with tech firms on tracking the coronavirus pandemic. This meant that authorities could use everyone's phone location data in studying the spread of the virus, which naturally raised a lot of privacy concerns.

According to a new report from The Wall Street Journal, the actual focus of the project is to track Americans' movements using location data collected from mobile ads, instead of relying on data from carriers. The efforts are also coordinated by academics at universities like Harvard, Princeton, and Johns Hopkins.

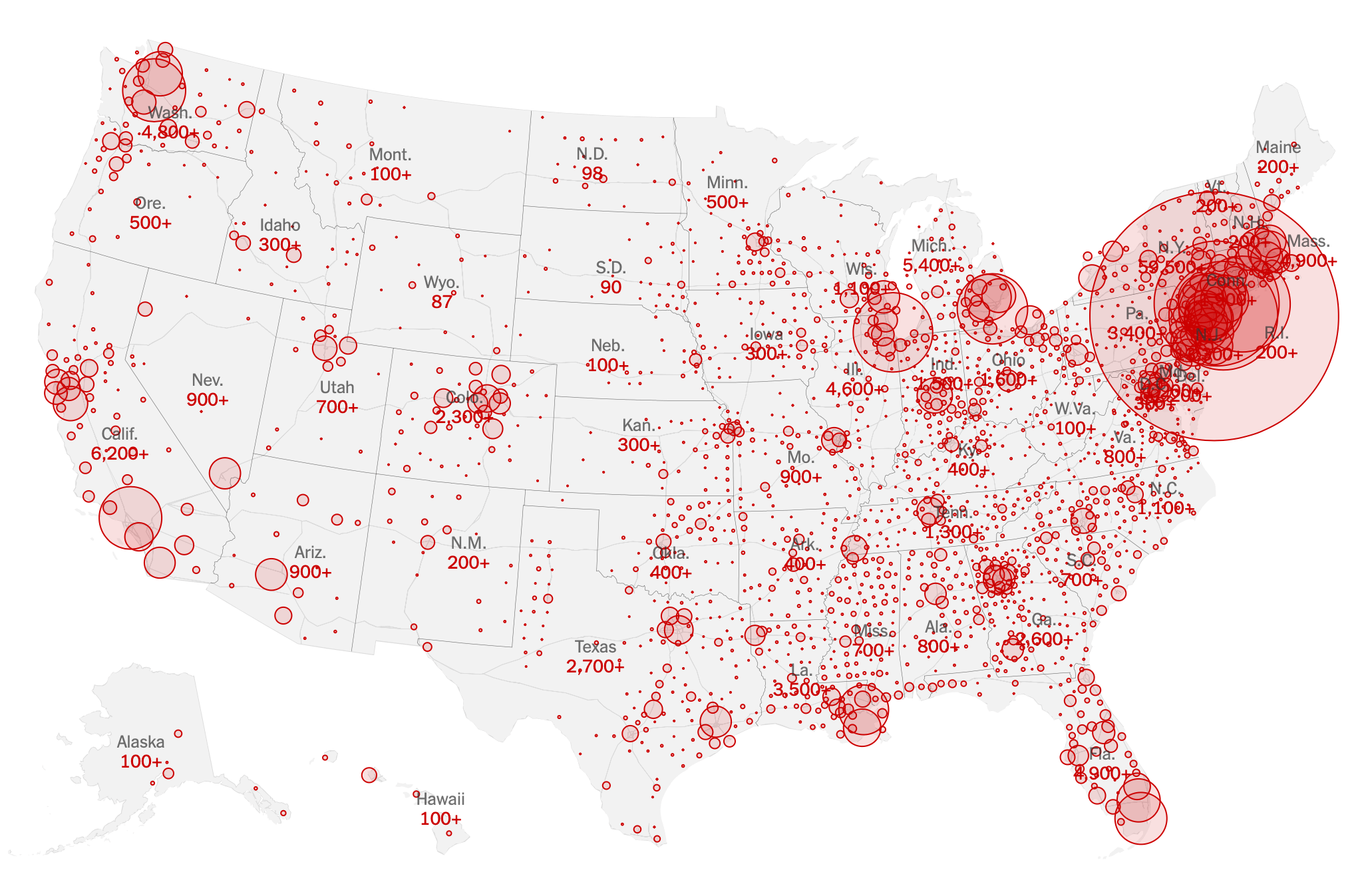

Specifically, federal officials along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are working with the mobile ad industry and they're looking to gather data about people from regions of "geographic interest." The end goal would be to create a government portal that would provide a heat map of how citizens are complying with stay-at-home orders in 500 American cities.

Want to see the true potential impact of ignoring social distancing? Through a partnership with @xmodesocial, we analyzed secondary locations of anonymized mobile devices that were active at a single Ft. Lauderdale beach during spring break. This is where they went across the US: pic.twitter.com/3A3ePn9Vin

--- Tectonix GEO (@TectonixGEO) March 25, 2020

The government has already received some data from the Covid-19 Mobility Data Network that shows, for example, that New Yorkers are still flocking to some parks despite the lockdown orders given by local authorities.

Another goal of the data collection is to generate economic metrics for measuring the impact of the pandemic on various sectors of the economy such as retail and transportation.

While researchers will no doubt use the data to better understand what we're dealing with, privacy advocates are right to be concerned. During the last few weeks, several countries have introduced new surveillance measures under the pretext of the pandemic.

For instance, China gives citizens a color code that represents how much of a contagion risk they pose to others, and every time they scan their health code their location is logged and sent to authorities. In addition to all that, those under a 14-day quarantine have their doors monitored by CCTV cameras, and drones warn people who don't use a mask to wear one as soon as possible.

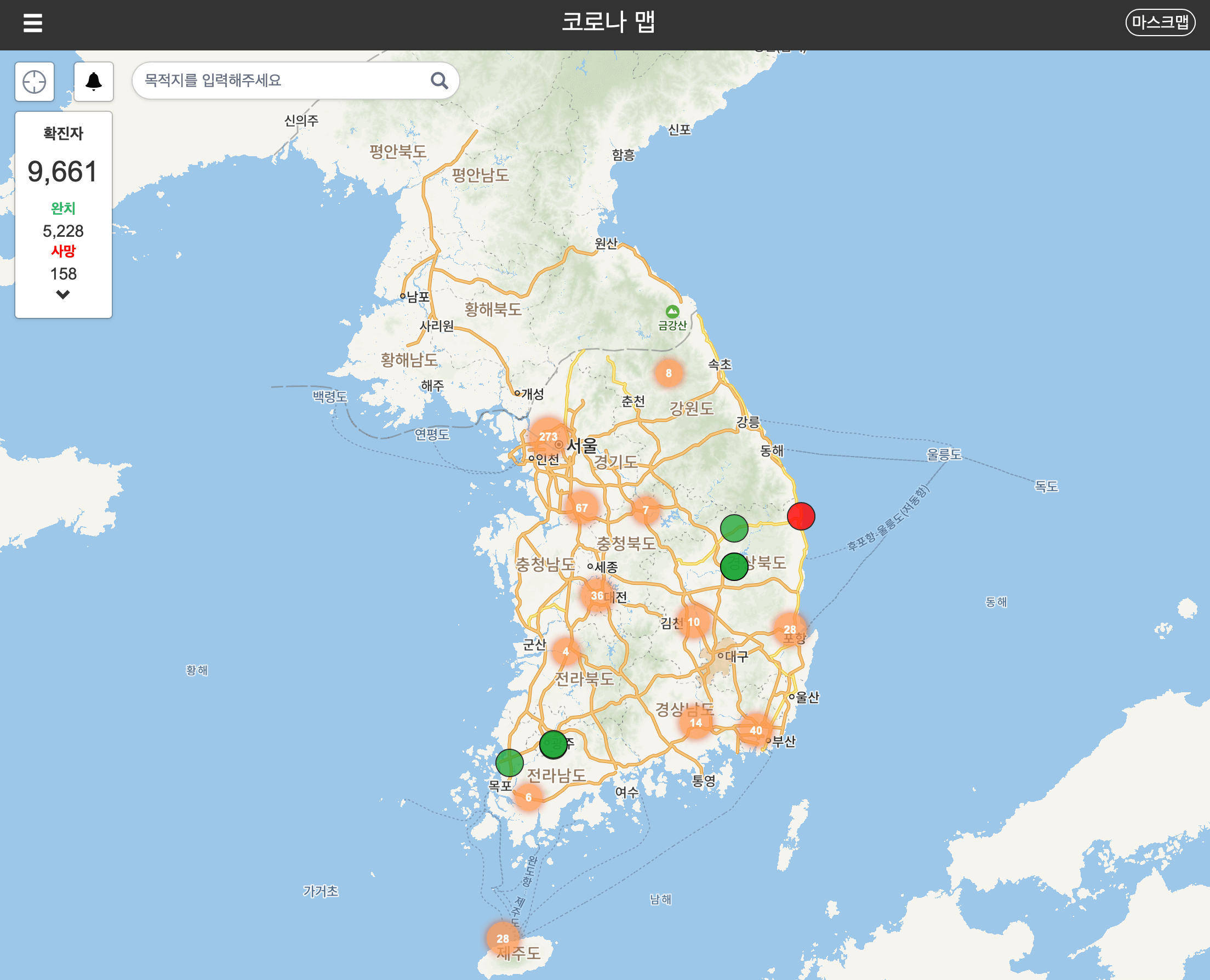

South Korea uses CCTV cameras too, and tracks credit card transactions, smartphone location data, and conversations of all people who are confirmed cases of coronavirus infection or otherwise asymptomatic carriers. This makes it possible to map the hot spots so people can be aware that they've probably been near someone that has the virus.

In Singapore, the government made an app that uses Bluetooth signals to achieve the same goal. In Hong Kong, citizens were asked to wear a wristband that's linked to a smartphone app and is able to alert authorities if someone left quarantine.

Israel's security experts are using phone location data to track their movements in near-real time so they can monitor the spread of the coronavirus and assess the need for tighter quarantine and lockdown measures. Interestingly, Israel's Shin Bet has been secretly gathering smartphone location data for years to combat terrorism, but now that it has shifted that focus towards a more practical purpose (saving lives), citizens seem tolerant about the invasion of their privacy.

Taiwan employs an "Electronic Fence" system that is supposed to alert authorities every time a quarantined person wanders too far from their home for too long. This allows the country to quickly dispatch police forces where people break the rules, with the average response time being around 15 minutes.

India has recently entered a lockdown, and is using a combination of phone call records, surveillance camera footage in big cities, and phone location data to track people that are known to have been in contact with patients diagnosed with Covid-19 and people who arrive at airports or train stations.

In Europe, several telecom companies like Deutsche Telekom and Vodafone have committed to a plan where they share data with health officials in Italy, Austria, Germany, and the UK to monitor people's movements and potential hotspots. However, due to stringent privacy regulations, they're only using anonymized data to give authorities a good idea on the overall effectiveness of social distancing and compliance with lockdown orders.

Spain even employs drones that scold people who don't stay indoors, hoping that people will understand the importance of flattening the curve of infections. In Australia, companies have unveiled drones that are able to detect people with Covid-19 and other respiratory syndromes, which are pending approval for deployment around the country.

Russia has been relatively reserved about its methods to contain the spread of the coronavirus inside its borders, but it too has now started tracking people using phone geolocation data. Just a week ago, the government ordered the creation of an alert system that offers instructions via SMS to people that have been in close proximity to Covid-19 patients or possible carriers of the virus, telling them to self-isolate in their homes. Moscow officials are even discussing the possibility of using facial recognition systems to aid the efforts.

There is a real possibility that some of these surveillance systems will persist until after the pandemic is over, and might not even get scaled down after governments get used to them. The biggest worry should be the difficulty of keeping all this data truly anonymous, and the fact that governments are quiet about implementing any safeguards to prevent abuse or leaks.

Hackers are also ramping up their attack and phishing operations to hit companies with employees that have been allowed to work from home, as well as attempts to get into the treasure troves of personal information that governments are now collecting to fight the pandemic. So far, carries told The Wall Street Journal that the US government hasn't requested any metadata from them, but in the EU they do so while still complying with GDPR.

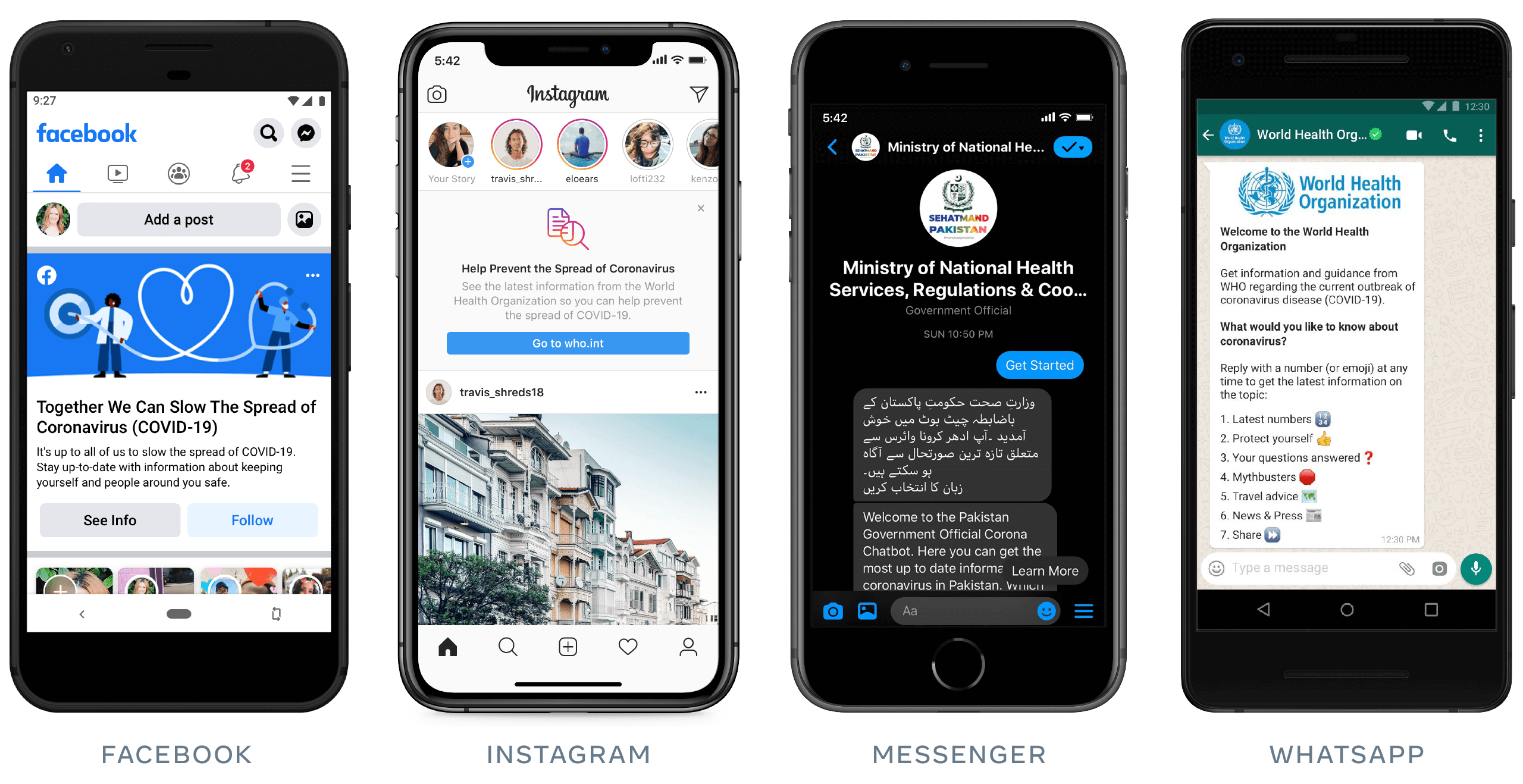

The problem of surveillance extends to companies like Facebook and Google. The rumor mill churned reports of the government supposedly asking the two companies to share users' phone location data. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg promptly denied the claims, noting "I don't think it would make sense to share people's data in a way where they didn't have the opportunity to opt in to do that."

It's worth noting that Facebook does have a disease mapping tool that it says is using anonymized data to offer a view of general trends for the spread of diseases, including Covid-19. The company is currently working with the World Bank, the IMF, and the Inter-American Development Bank in a new partnership that seeks to help countries assess the spread of the disease and decide where to focus testing, prevention, response, and recovery efforts. This will also help with the distribution of a vaccine once it becomes available.

The takeaway is that there's a clear need to balance surveillance efforts that track Covid-19 with appropriate privacy protections. The Electronic Frontier Foundation says there's no evidence of the effectiveness of these tools so far, and that transparency should be exercised at all times by authorities who want to use them.

Self-screening apps and websites could be a solution. Another option is the Private Kit: Safe Paths app developed by MIT, which tracks your movements and shares that data with other users in a way that is anonymous.

As the name suggests, the app will help you see if you've recently crossed paths with someone that might be carrying the coronavirus. If need be, you can also choose to share that information with health officials and make it public. The obvious disadvantage of these approaches is that they need to garner a lot of users to be effective. Giving people a false sense of security due to incomplete or inaccurate data could make the situation worse for everyone.