Editor's take: Broadcom was once a leading semiconductor company, and then it started buying enterprise software companies. The finance people recognize Broadcom for it is, and while the technology people recognize it as well, they just do not want to accept it. And we cannot blame them for that sentiment.

Broadcom began its existence as a spin-off of a spin-off. Twenty years or so ago, Hewlett Packard began its process of miniaturization. First spinning off Agilent which contained a hodgepodge of businesses that were not related to PCs or printers. Agilent in turn split itself into several more pieces, one of which was HP's one-time internal chip business, rechristened as Avago. We followed Avago closely for many years as sell-side analysts. Buried deep inside HP, we knew it sold filters that went into mobile phones and would occasionally provide some really interesting, but obscure piece of information. Then the spin-off happened.

Editor's Note:

Guest author Jonathan Goldberg is the founder of D2D Advisory, a multi-functional consulting firm. Jonathan has developed growth strategies and alliances for companies in the mobile, networking, gaming, and software industries.

Avago came to life through private equity ownership, and as far as origin stories go, this was the key clue to what would happen next. Avago CEO Hock Tan realized something early on that most other semiconductor CEOs did not - semis had stopped being a growth industry.

The go-go days of the 80's and 90's were over, and now semis were intensely competitive, heavily cyclical and poorly margined. So Avago went on a buying spree, buying more companies than we can count, and driving the stock up 3,000% (three thousand percent) in a decade and half.

The secret to this success was a fairly straightforward playbook. Buy companies which had leading positions in markets with few competitors. Then shed segments that sold into competitive sectors, slash management and corporate overhead, and drive cash flow - which allowed for more leverage and thus firepower for the next acquisition. And repeat.

The company was wildly successful at this, and effectively catalyzed a thorough consolidation of the US semiconductor industry, which went from something like 2,000 companies twenty years ago to around 200 today.

For companies that got acquired the integration process was bracing. The new management team would eliminate every expense they could find - no more company swag, no more free coffee, famously no corporate IT department. For junior managers that survived the cuts this was fantastic. They were given autonomy, the elimination of bureaucracy, fat option packages and a crushing workload.

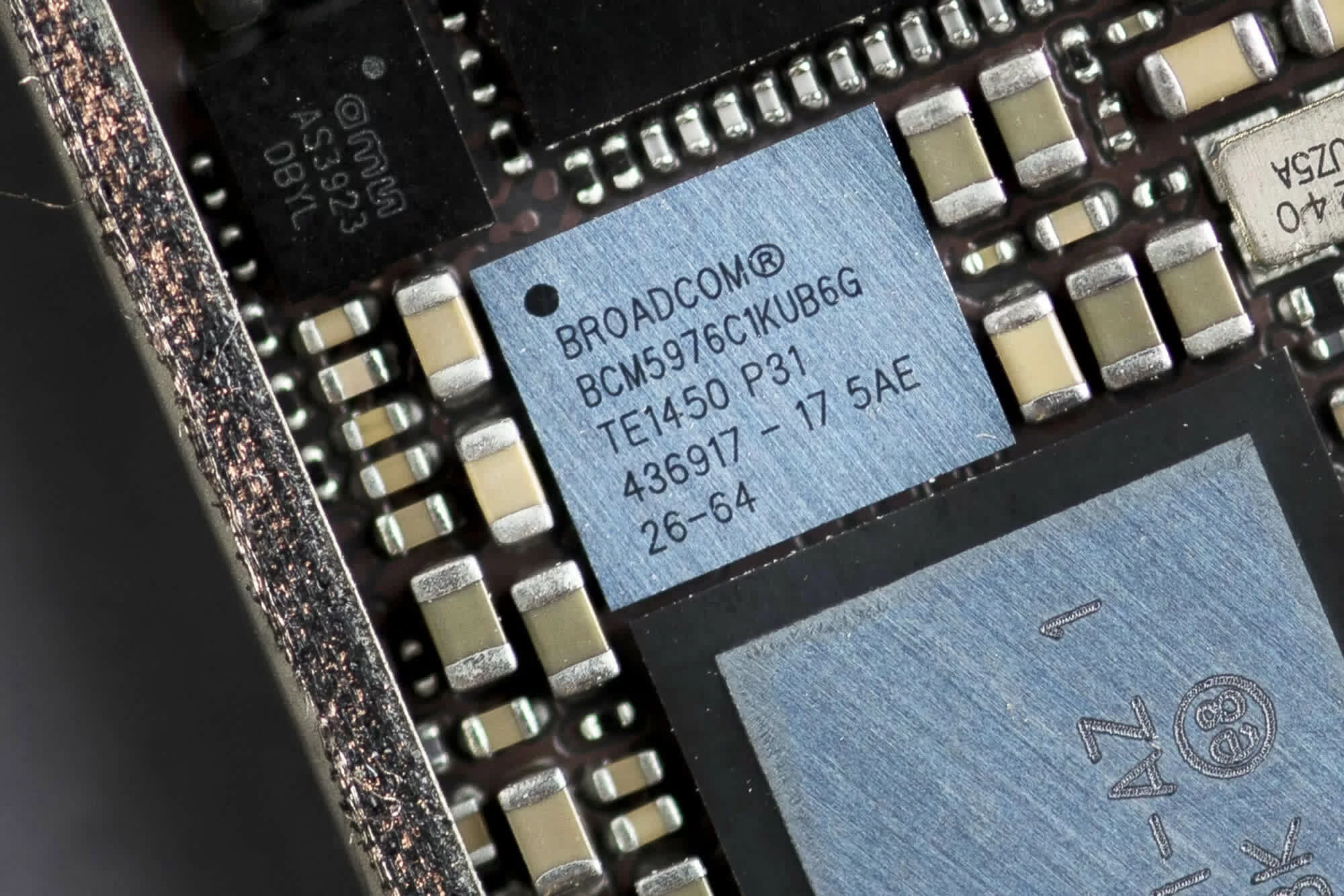

Over time, another trend became apparent as well - the company would dramatically lower R&D, a topic we will return to below. Another important skill Avago had was that its CEO and deal team became experts and finding the non-financial tools that would convince the board of targets to sell. Sometimes that meant retirement deals for outgoing executives, an office and title for a founder, or the preservation of a company's name. So when they acquired Broadcom in 2015, Avago changed their name because that is what it took to get the deal done.

The story goes that when Alexander the Great reached the Indus River he sobbed, lamenting the fact that there were no more lands left to conquer. Broadcom reached their Indus in 2019 when they failed to acquire Qualcomm, due to a hazy last-minute CFIUS order from the US government. Like all other successful roll-up stories, Broadcom needed to keep acquiring bigger businesses to keep the machine moving. By 2019, there were really only two companies large enough to move the needle for Broadcom - Qualcomm and Intel. Qualcomm was out of bounds, and Intel was too big (then) to contemplate.

And so Broadcom turned to software companies. There are plenty of large targets in this space. These companies do not necessarily have dominant positions in markets the way Broadcom's semis targets did, but they do have very sticky relationships with customers who are locked into long-term contracts and multiple IT dependencies. This means steady cash flows.

The truth is Broadcom is not a semiconductor company. Nor is it a software company. It is a private equity fund, maximizing cash flow from an endless series of acquisitions. This is disheartening to many in the semis industry and probably confusing to those in software. It is certainly proving to be a challenge for sell-side semis analysts who now have to master SaaS metrics. But for shareholders, it remains a compelling model.

One thing we have learned about Broadcom over the years is that they are constantly looking for new deals. So we can say from experience that the day the VMWare acquisition closes the bankers will get calls asking "What is next?"

How long can this go on? Roll-ups have a few big problems. One is the constant quest for new deals we mentioned above. The second is integration. At some point these organizations get so large, they start to trip over themselves. Broadcom has largely avoided this problem by pushing so much autonomy down to individual units, but at some point this has to just bog down. especially when everything is under the umbrella of a single public company.

The other problem is that the whole model is dependent on steady cash flows from the underlying businesses. This is the reason that private equity firms avoided technology for so long, there is technology risk embedded in these companies that does not necessarily exist in the more traditional companies the private equity funds typically favor. And this is why we keep an eye on Broadcom's semis businesses R&D. There are no gaping flaws today - they remain incredibly strong in the networking space and are the dominant party in the duopoly around BAW RF filters for mobile phones.

That being said, we hear more and more from people in the networking business that they are disappointed in the pace of development at Broadcom. New chips and features take longer and longer to arrive, opening the door to start-ups and internal solutions within the hyperscalers. And in RF, there is a real possibility of technological disruption to at least some portion of the BAW filter market, Qualcomm and Murata, seem to feel pretty strongly about that.

Admittedly, the team at Broadcom are very savvy. If any of their businesses start to show signs of peaking, they will sell or spin them off without a backwards glance. Of course, most buyers are probably aware of this, and so far Broadcom has not generated a single exit from its portfolio, other than the occasional post-merger sale of an unwanted business line.

As it stands now, Broadcom can probably keep this model going for a long time still. There is an ocean of software targets out there, and they all got much cheaper this month. Our best guess is that the only thing could slow Broadcom down is the executive team's energy level. Hock Tan is now about 70 years old, and our guess is that he has no interest in retiring to grow wine in Napa Valley any time soon.