Why it matters: After spending 45 years in space, the Voyager 2 mission is still going strong. Energy supply isn't what it used to be, though, so NASA is working on new "tricks" that can extend the mission of the everlasting space probe even further.

Launched on August 20, 1977, just 16 days before its twin Voyager 1, the Voyager 2 space probe is now cruising outside the protective bubble of the Solar System in a region known as the heliosphere. The exploration mission lasted way longer than NASA planned, and it could even continue for many more years to come if a new "power strategy" implemented by the space agency turns out to be successful.

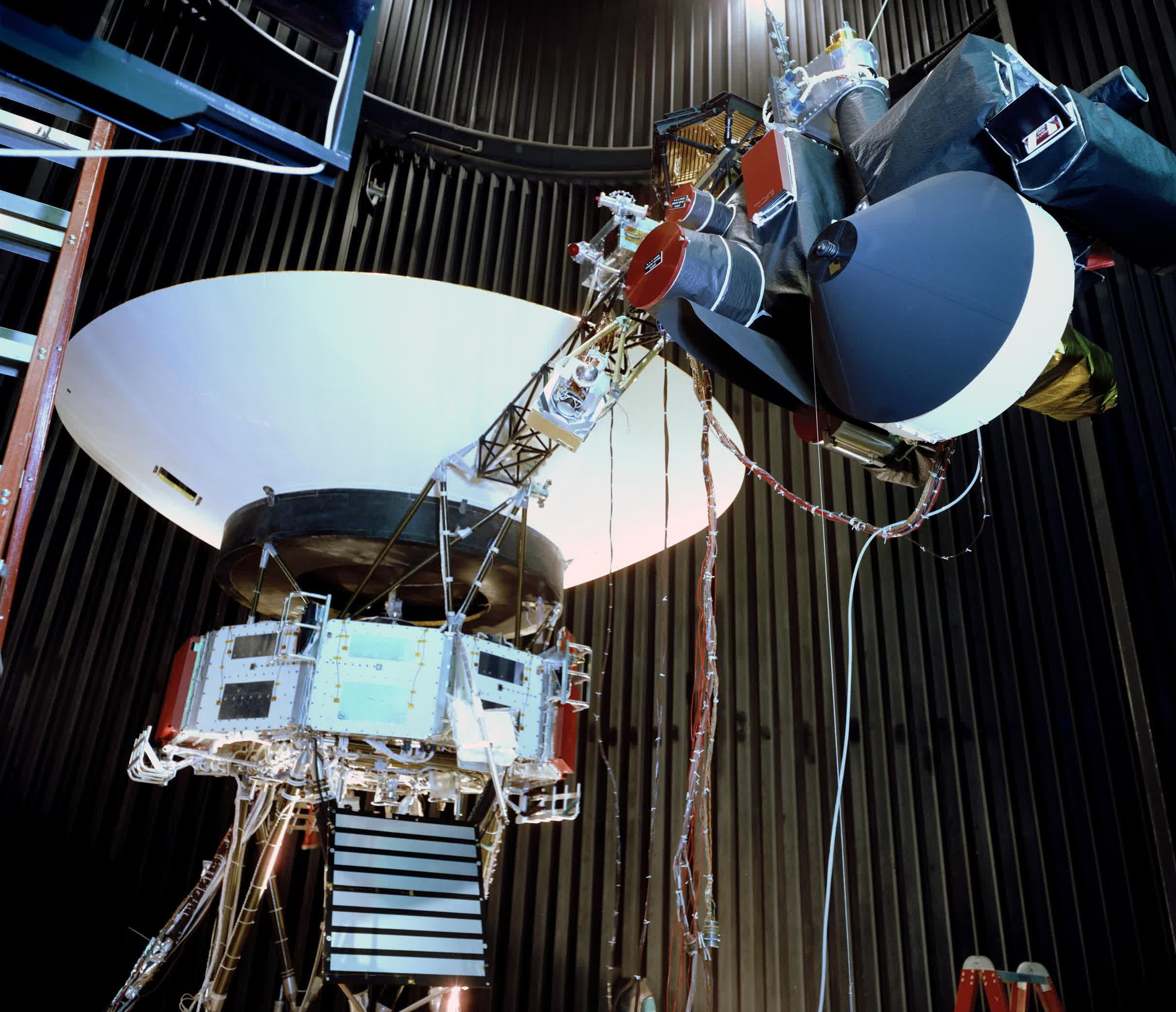

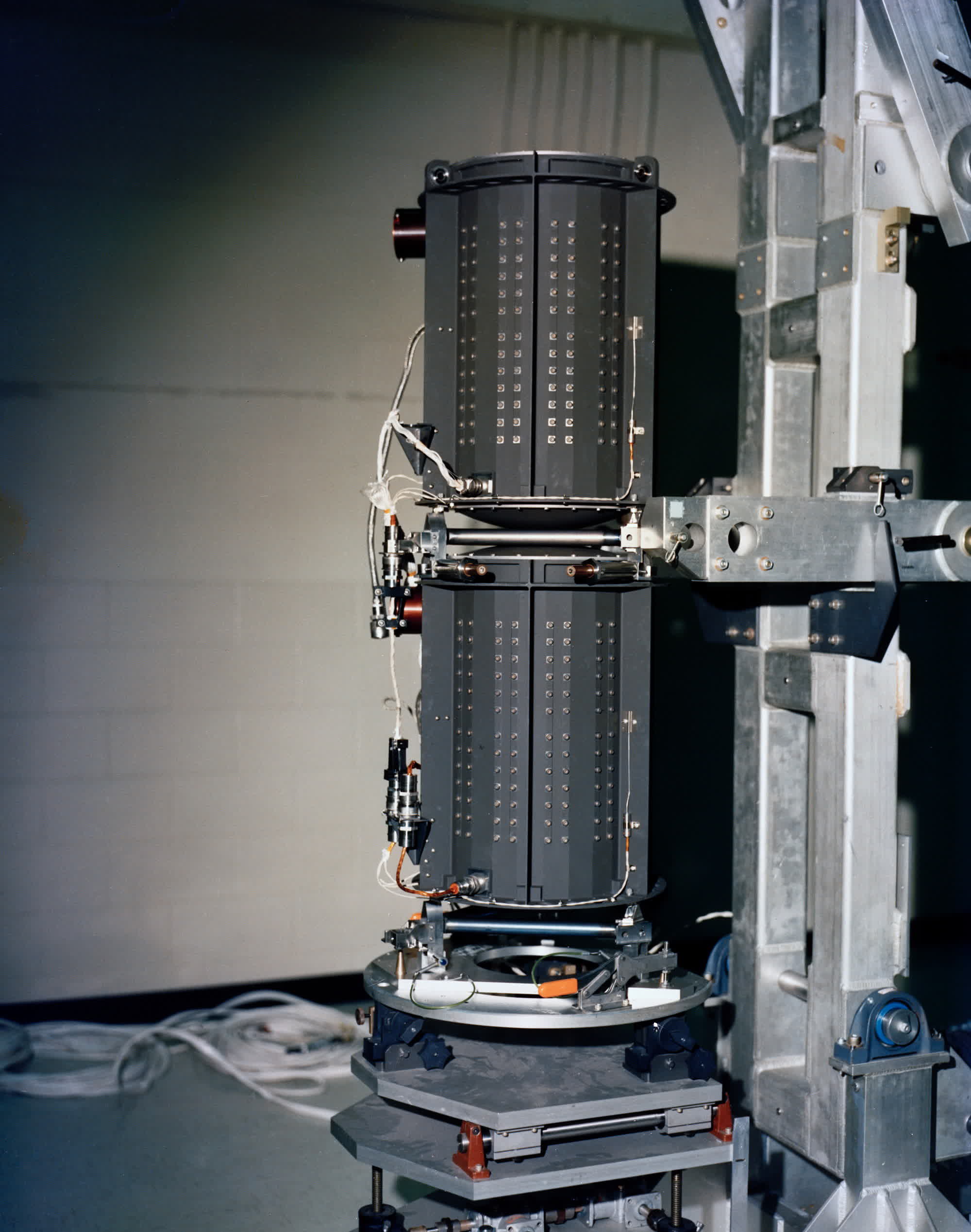

Right now, Voyager 2 is employing five different science instruments to study the interstellar space outside the heliosphere's magnetic bubble. The probe is powered by a set of three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTG), which are essentially nuclear generators that convert heat from decaying plutonium-238 atoms into electricity.

After 45 years, the nuclear generators of Voyager 2 cannot possibly produce the same amount of energy as before. NASA was considering shutting down one of the instruments to keep the other four in working order, but the agency ultimately decided to try an alternative solution that could keep all the five instruments running until at least 2026.

NASA engineers have already turned off heaters and other "non-essential" components of the Voyager 2 mission. Now, to avoid shutting one of the probe's science instruments down, the agency has decided to use a small amount of backup power from the RTG reserved to avoid potentially dangerous voltage fluctuations.

Voyager 2 is equipped with a voltage regulator which triggers the backup circuit if a fluctuation in voltage is detected, NASA explains, protecting the instruments from damage. Even after more than 45 years of flight, the electrical systems on both Voyager probes have remained relatively stable, so NASA thinks that a tighter voltage regulation is not essential anymore.

"Variable voltages pose a risk to the instruments," Voyager's project manager at JPL Suzanne Dodd explains, but NASA has determined that it's a small risk worth taking with the big reward of "being able to keep the science instruments turned on longer." JPL has been monitoring the spacecraft flight for a few weeks, and the new approach to power consumption seems to be working as expected. The team will keep monitoring electric voltage to eventually respond if it fluctuates too much.

The Voyager mission was originally designed to last only four years, sending the twin probes beyond gas giants Saturn and Jupiter. NASA extended the mission to make Voyager 2 visit Neptune and Uranus, then extended the mission a second time in 1990 to send the probes outside the heliosphere. Voyager 1 reached the outermost border of our Solar System's magnetic influence in 2012, while Voyager 2 got there (traveling in a different direction with a lower cruising speed) six years later in 2018.