Didn't the shuttle do the same thing? Throttled engines back during Max Q. Is there some sort of acceleration issue? The dragon capsule has already shown it's launch escape capability, which if I remember right can be used all the way up to 160,000ft. B ut it doesn't matter Musk already said they arn't using heavy for lunar missions. I could see them using the heavy to put a transport vehicle into LEO then shuttling people up with the Falcon 9.

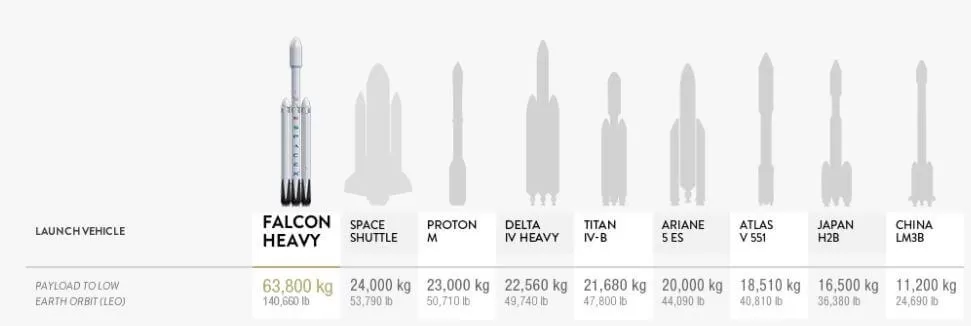

Block 1 SLS can do 70 metric tons to LEO current Falcon heavy is 63, from there NASA says moon payload, SpaceX says mars payload, they have different goals it would seem

. By the time they get block 1B running or block 2, there should be a upgraded falcon 9 and falcon heavy and BFR should be doing initial testing.

The shuttle waited to throttle its engines up until after max-Q. The SRBs provided most of the life through max-Q, and the Shuttle engines were ignited on the pad out of an abundance of caution. The SRBs stayed at full "throttle", given that they can only be "throttled" by playing with grain structure and mixture during manufacturing and fuel loading. But they're a solid fuel, once lit, they are going to stay lit.

Escaping a failing launch isn't just an acceleration issue, its punching through the shockwaves of supersonic and transonic flow, and then surviving the deceleration as you pass back into subsonic territory - all while something is going catastrophically wrong. But its not the act of escaping that NASA will be worried about, but the likelihood of needing to escape. Throttling down and then back up with liquid fueled engines will spook them enough when evaluating it for manned launches. What if they don't throttle dow? What if they don't throttle back up? what is they don't stop throttling back up? What if they throttle up too soon, too late, too quickly, too slowly? What if the throttling breaks something? These are all questions NASA and the FAA are going to want answers to. They are going to pay it very close attention to performance, over these next few launches - and SpaceX has handicapped themselves by re-using their rockets. With the SLS, one-and-done, they is no rocket to inspect for damage and begin to asses MTFBs. With The Falcon line, there are. SpaceX is going to have to separate what is expected wear and tear for an average F9 flight, and what is caused by the larger forces of a F9 booster being put into an FH configuration.

Meanwhile, the SLS will show up on the scene pretty much already cleared for human launch. EM-1 will be unmanned, but EM-2 will almost certainly be manned. If FH and Dragon get cleared for human launches before SLS and Orion, I'll be stunned. I also wouldn't be surprised if Musk does the math and just decides to skip getting the FH cleared for manned missions and go straight to getting BFR cleared, since the FH will have better returns on payload missions. Who is paying to send men to the moon, and are they paying enough to warrant all the expensive of getting it cleared for human missions - when BFR will be a more capable platform with (likely) few risks to have to explain and justify to NASA and the FAA?

Once you get out of Earth's gravitational pull, a given rocket will have 'similar' payload capacities to most destinations - depending on velocity. So its not surprising that they have similar launch capacities, but going towards different stated definitions. Boeing states the Moon to be conservative, SpaceX states Mars to be aspirational. In reality, they both probably lift similar amounts to the same destinations. Going in towards the sun is a different story; always more expensive kg-for-kg than going away from the sun. They might begin to differ in payload capacity and capability if someone wants to use them for a Venus, Mercury, or Sol mission.