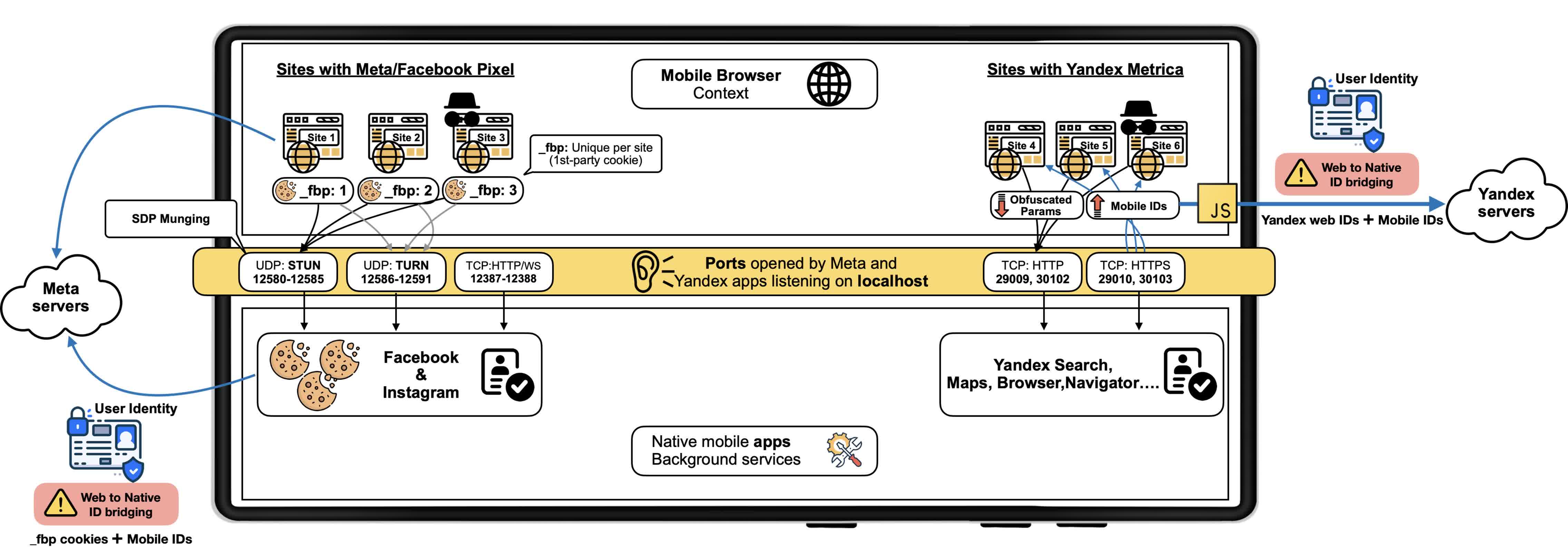

A hot potato: For years, the privacy of Android users browsing the web has been quietly compromised by a sophisticated tracking method employed by two of the world's largest tech companies: Meta and Yandex. According to recent research, both companies have exploited legitimate browser-to-app communication protocols to covertly link anonymous web activity with the identities of users logged into native apps like Facebook, Instagram, and various Yandex services on Android devices.

The research, extensively analyzed by Ars Technica, focuses on the widespread use of analytics scripts such as Meta Pixel and Yandex Metrica. These tools are embedded across millions of websites, ostensibly to help advertisers track campaign performance. However, behind the scenes, they enable a process that circumvents the privacy protections built into Android and major web browsers.

At the core of the issue is the exploitation of Android's permissive local port communication. While Android's sandboxing and browser storage partitioning are intended to keep web and app data siloed, Meta and Yandex have discovered methods to bypass these safeguards, effectively enabling cross-app tracking.

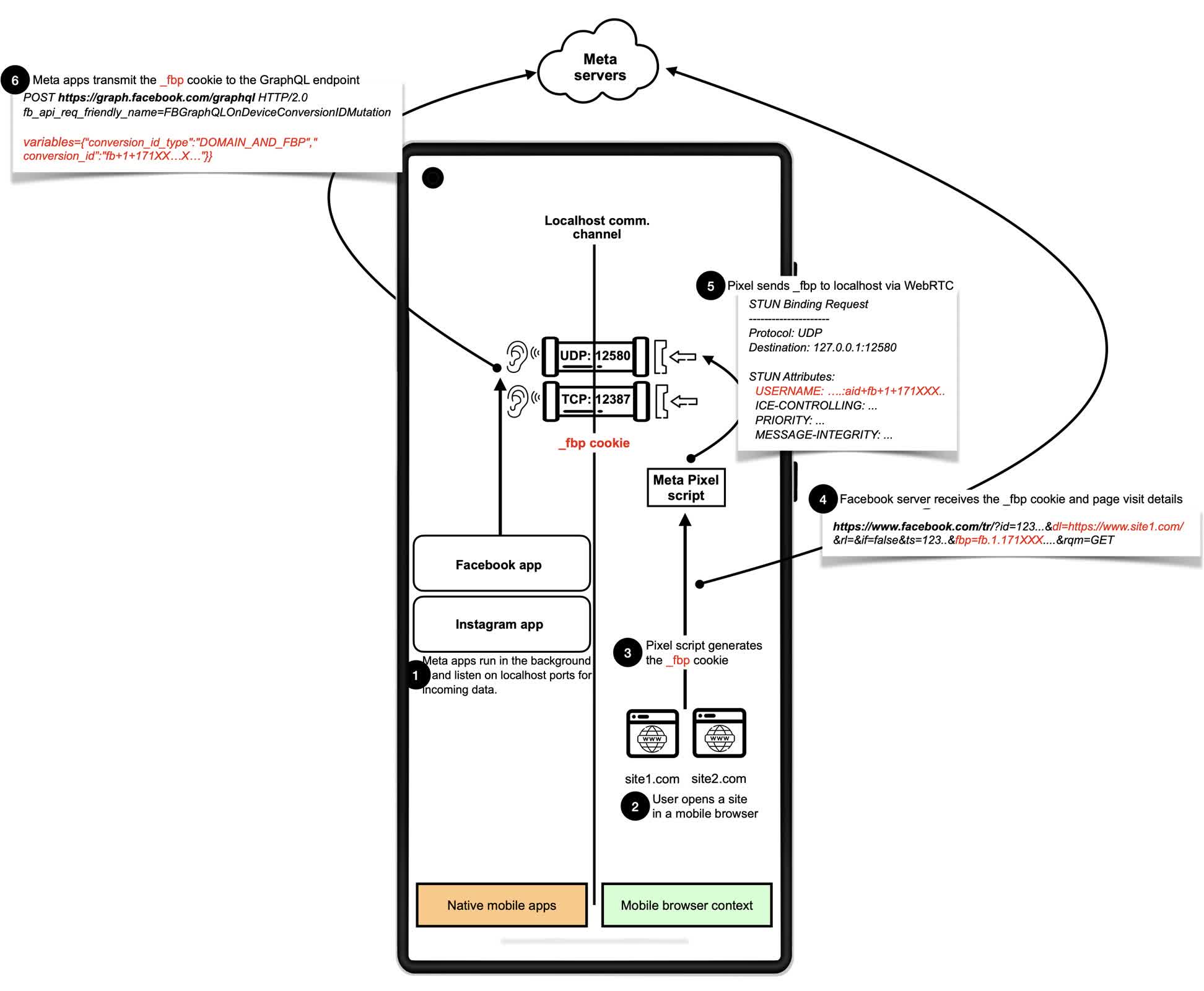

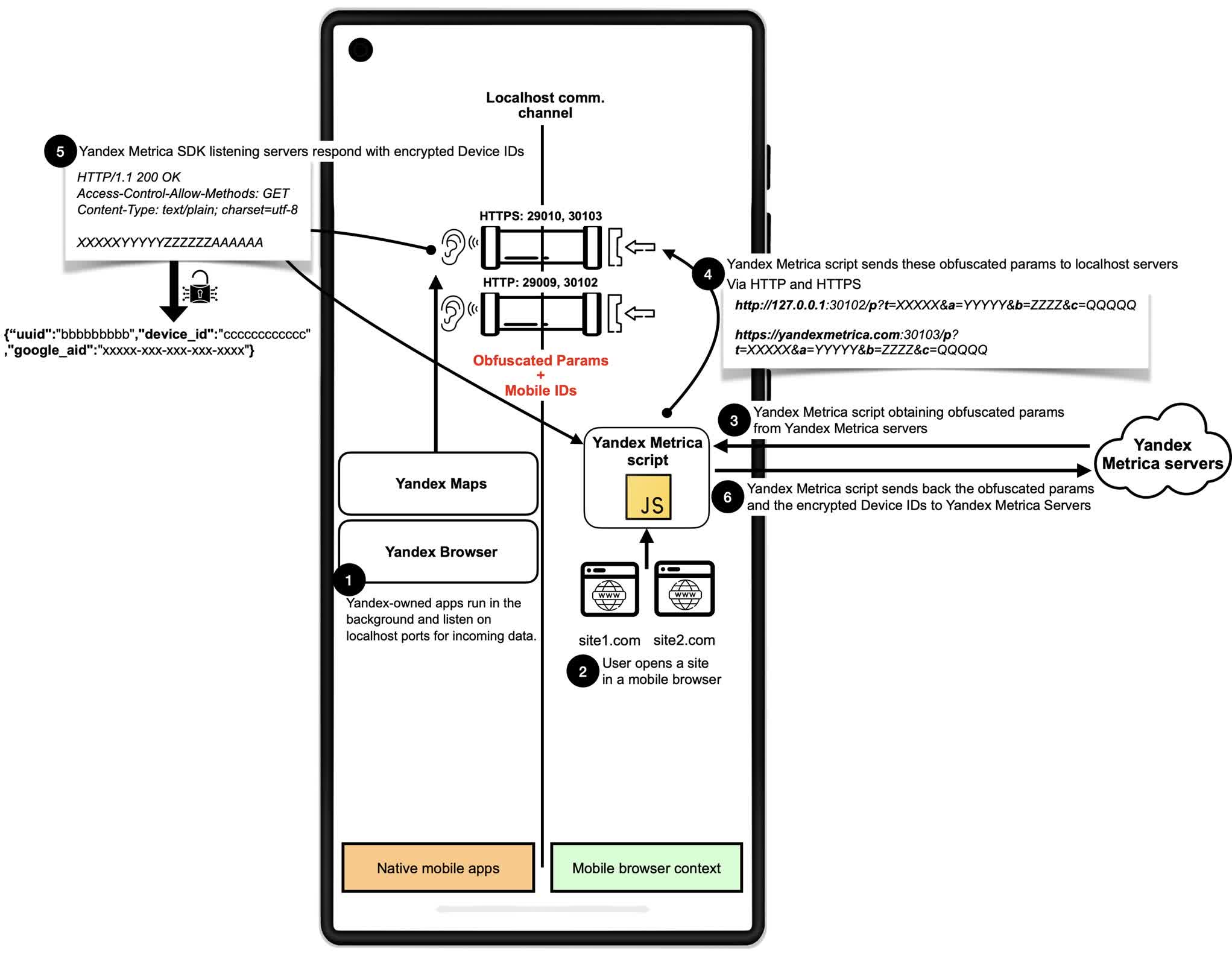

The trackers send unique web identifiers – such as cookies – through local ports monitored by their corresponding apps. This allows Meta and Yandex to link a user's browsing history directly to their app account, even when users are browsing in private or incognito modes.

"What this attack vector allows is to break the sandbox that exists between the mobile context and the web context," Narseo Vallina-Rodriguez, one of the researchers who uncovered the practice, told Ars Technica. "The channel that exists allowed the Android system to communicate what happens in the browser with the identity running in the mobile app."

The technical implementation is complex but revealing. Meta Pixel, for instance, has employed a variety of methods since September of last year. Initially, it sent HTTP requests to port 12387; it later transitioned to using the WebSocket protocol over the same port.

Later, Meta adopted WebRTC, a protocol typically used for real-time communications like video calls. By manipulating Session Description Protocol SDP data through a technique known as SDP munging, Meta Pixel was able to embed tracking cookies into fields intended for connection information. This data was then sent as part of a STUN request to the local host, where the Facebook or Instagram app could intercept it and associate the activity with a specific user identity.

Yandex Metrica has employed similar tactics since at least 2017, sending HTTP and HTTPS requests to designated local ports monitored by its apps. Both Meta Pixel and Yandex Metrica are estimated to be embedded on millions of websites, with Meta Pixel alone found on approximately 5.8 million.

Google, the steward of Android, has acknowledged the abuse, stating that it violates both Play Store policies and user privacy expectations. "The developers in this report are using capabilities present in many browsers across iOS and Android in unintended ways that blatantly violate our security and privacy principles," a Google spokesperson said. The company has implemented some mitigations and is investigating further.

Meta, for its part, has paused the feature and is currently in discussions with Google. "We are in discussions with Google to address a potential miscommunication regarding the application of their policies. Upon becoming aware of the concerns, we decided to pause the feature while we work with Google to resolve the issue," according to a statement by the company.

Yandex has also stated that it is discontinuing the practice. The company claims it does not de-anonymize user data and insists the feature was intended solely to improve personalization within its apps.

Some browsers have taken proactive measures. DuckDuckGo and Brave, for instance, have blocked the abusive JavaScript and associated domains, preventing identifiers from being sent to Meta and Yandex.

Vivaldi, another Chromium-based browser, still forwards identifiers to local ports unless tracker blocking is enabled. Chrome and Firefox have rolled out targeted fixes, though researchers warn these are only partial solutions that could be bypassed with minor modifications to the trackers' code.

Gunes Acar, the researcher who first discovered Meta Pixel's local port access, emphasized that the dynamic between browser developers and trackers remains fluid. He described efforts to block these techniques as an ongoing struggle.

"Any browser doing blocklisting will likely enter into a constant arms race, and it's just a partial solution. Creating effective blocklists is hard, and browser makers will need to constantly monitor the use of this type of capability to detect other hostnames potentially abusing localhost channels and then updating their blocklists accordingly."