A big topic in semiconductors today is the recognition that the real market opportunity for AI silicon is going to be the market for AI inference. We think this makes sense, but we are starting to wonder whether anyone is going to make any money from this.

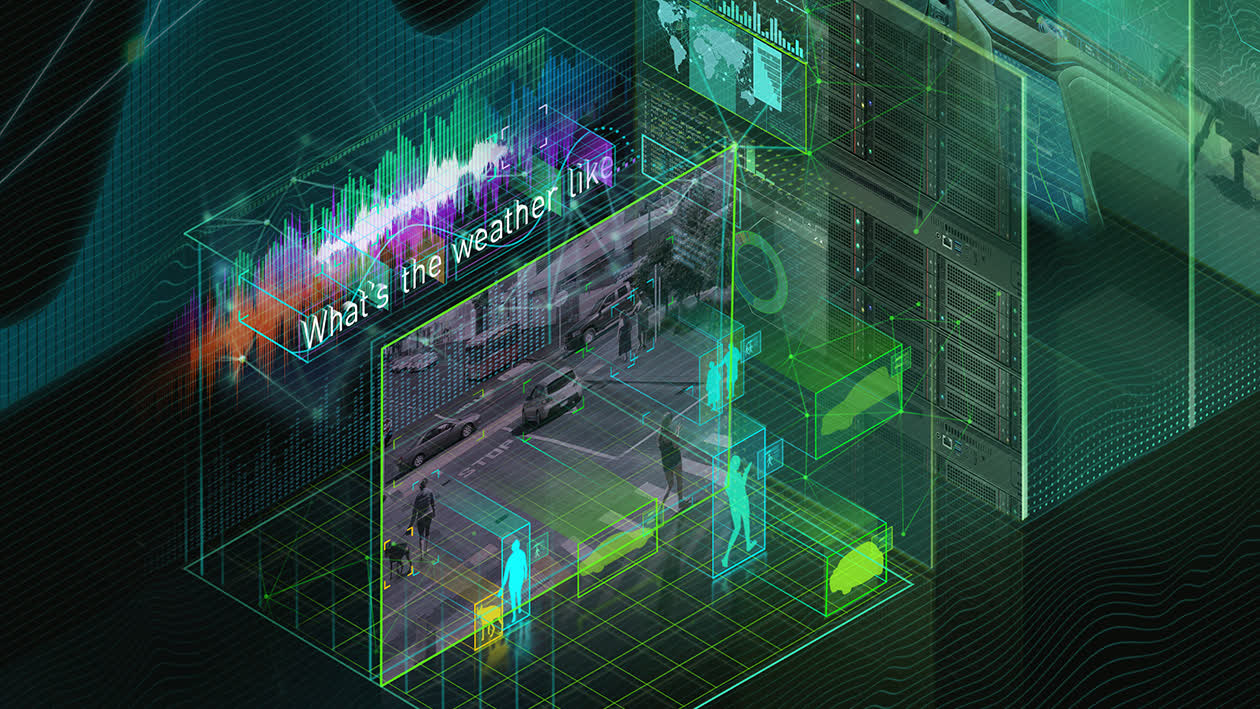

The market for AI inference is important for two reasons. First, Nvidia seems to have a lock on AI training. True, AMD and Intel have offerings in this space, but let's classify those as "aspirational" for now. For the time being, this is Nvidia's market. Second, the market for AI inference is likely to be much larger than the training market. Intel's CEO Pat Gelsinger has a good analogy for this – weather models. Only a few entities need to create weather prediction models (NASA, NOAA, etc), but everyone wants to check the weather.

Editor's Note:

Guest author Jonathan Goldberg is the founder of D2D Advisory, a multi-functional consulting firm. Jonathan has developed growth strategies and alliances for companies in the mobile, networking, gaming, and software industries.

The same holds for AI, the utility of models will be derived by the ability of end-users to make use of them. As a result, the importance of the inference market has been a consistent theme in all the analyst and investor events we have attended recently, and even Nvidia has shifted their positioning lately to talk a lot more about inference.

Of course, there are two pieces of the inference market – cloud and edge. Cloud inference takes place in the data center and edge inference takes place on the device. We have heard people debate the definition of these two recently, the boundaries can get a bit blurry. But we think the breakdown is fairly straightforward, if the company operating the model pays for the capex that is cloud inference, if the end user pays the capex (by buying a phone or PC) that is edge inference.

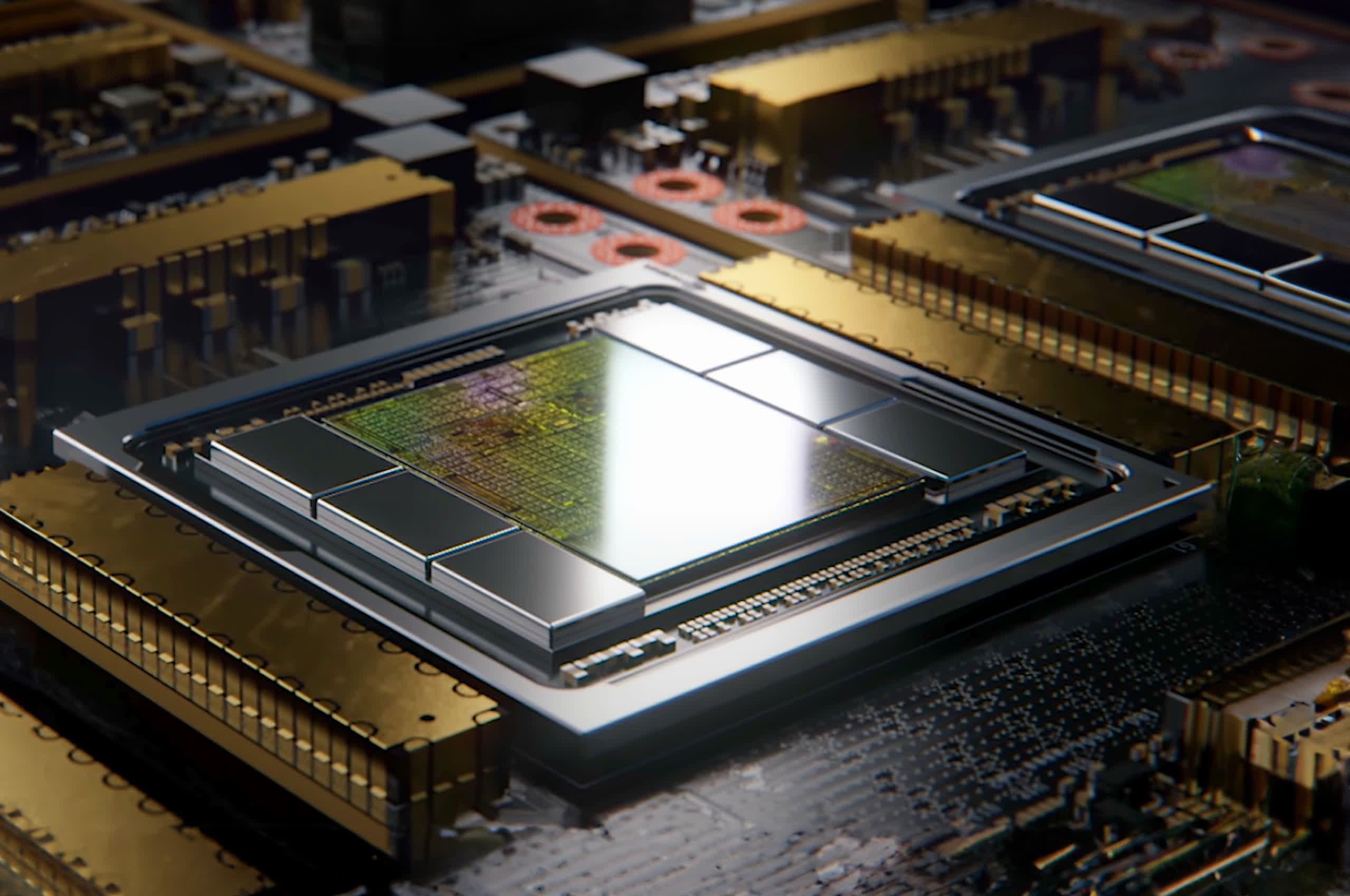

Cloud inference is likely to be the most interesting contest to watch. Nvidia has articulated a very strong case for why they will transfer their dominance in training to inference. Put simply, there is a lot of overlap and Nvidia has Cuda and other software tools to make the connection between the two very easy. We suspect this will appeal to many customers, we are in an era of "You don't get fired for buying Nvidia", and the company has a lot to offer here.

On the other hand, their big competitors are going to push very hard for their share of this market. Moreover, the hyperscalers who will likely consume the majority of inference silicon have the ability to break the reliance on Nvidia whether by designing their own silicon or making full use of the competition. We expect this to be the center of a lot of attention in coming years.

The market for edge inference is a much more open question. For starters, no one really knows how much AI models will rely on the edge. The companies that are operating these models (especially the hyperscalers) would really like for edge inference to predominate. This will greatly reduce the amount of money they have to spend building all those cloud inference data centers. We suspect that the economics of AI may not pencil out if this is not possible.

The reality is that we do not know what consumers would be willing to pay because we do not really know what AI will do for consumers.

That being said, this vision comes with a significant caveat – will consumers actually be willing to pay for AI? Today, if we asked the average consumer how much they would pay to run ChatGPT on their own computer we suspect the answer would be $0. Yes, they are willing to pay $20 a month to use ChatGPT, but would they be willing to pay more to get it to run locally. The benefit of this is not entirely clear, maybe they could get answers more quickly but ChatGPT is already fairly fast when delivered from the cloud. And if consumers are not willing to pay more for PCs or phones with "AI capabilities" then the chip makers will not be able to charge premiums for silicon with those capabilities. We mentioned that Qualcomm faces this problem in smartphones, but the same applies to Intel and AMD for PCs.

We have asked everyone about this and have yet to get a clear answer. The reality is that we do not know what consumers would be willing to pay because we do not really know what AI will do for consumers. When pressed, the semis executives we spoke with all tend to default to some version of "We have seen some incredible demos, coming soon" or "We think Microsoft is working on some incredible things". These are fair answers, we are not (yet) full-blown AI skeptics, and we imagine there are some incredible projects in the works.

This reliance on software begs the question as to how much value there is for semis makers in AI. If the value of those AI PCs depends on software companies (especially Microsoft) then it is likely to assume that Microsoft will capture the bulk of the value for consumer AI services. Microsoft is kind of an expert at this. There is a very real possibility that the only boost that comes from AI semis will be that they spark a one-time device refresh. That will be good for a year or two, but is much smaller than the massive opportunity some companies are making AI out to be.