Why it matters: Twitter is finally testing a feature it announced earlier this year: the ability to limit how many people reply to a tweet. It might be a welcome addition for most people, but it could pose legal problems for public officials who regularly use the service, including President Trump.

Back in January, Twitter said it would be introducing a new tool that would allow users to select who can reply to their tweets. Now, the company is testing the feature with a "limited group of people globally" on Android, iOS, and the web app.

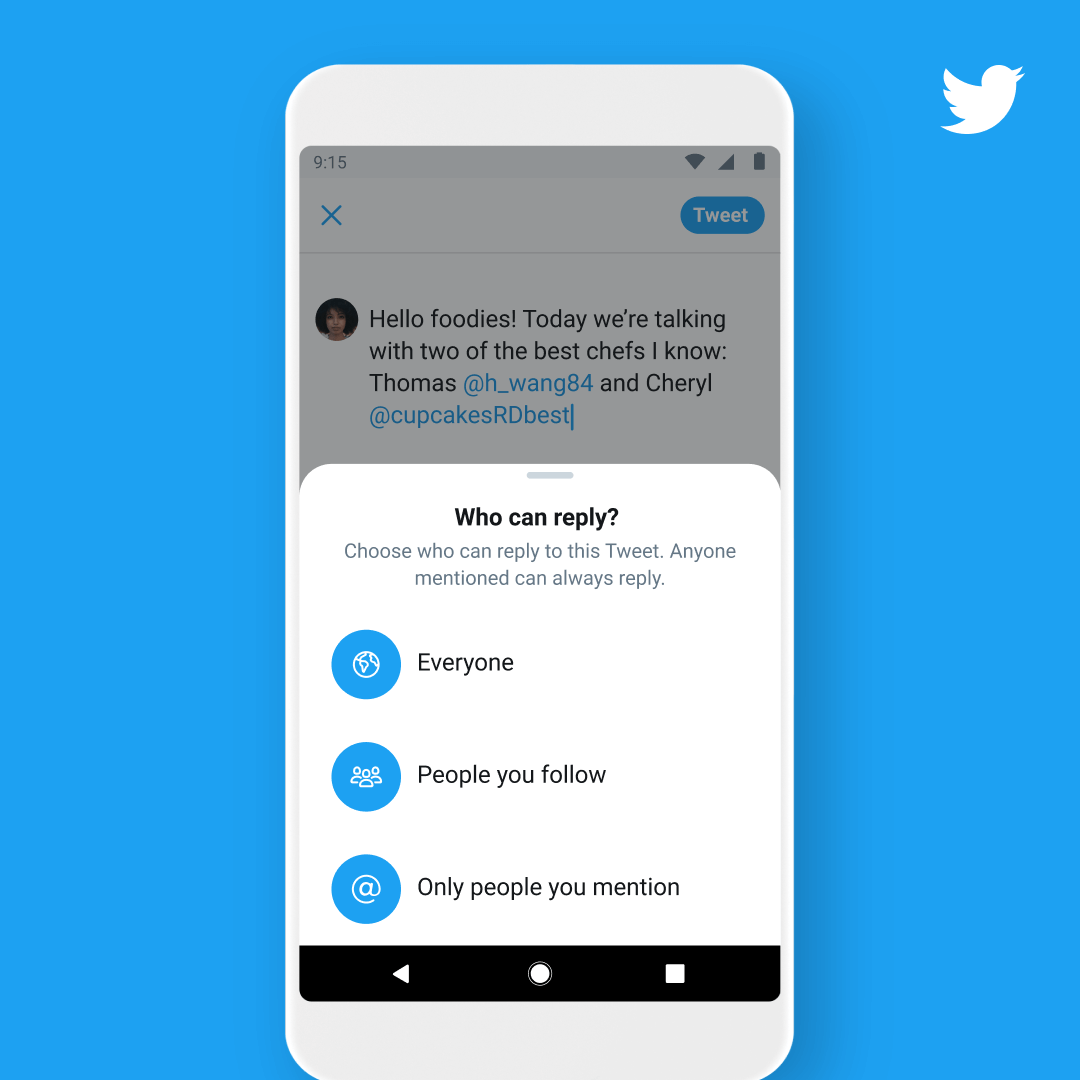

Using the feature presents a few options when posting a tweet: keeping the current default setting of allowing anyone to reply, only letting followers reply, or only allowing those who are mentioned to reply. By choosing the last option and not mentioning anyone, users are effectively turning off all replies.

Testing, testing...

--- Twitter (@Twitter) May 20, 2020

A new way to have a convo with exactly who you want. We're starting with a small % globally, so keep your ? out to see it in action. pic.twitter.com/pV53mvjAVT

The change is designed to address the platform's long-running troll problem. "Twitter is where you go to see and talk about what's happening," writes Suzanne Xie, Director of Product Management at Twitter. "But sometimes, unwanted replies make it hard to have meaningful conversations."

How much the features will stop the trolls remains to be seen. No matter what option is selected, everyone can still view, retweet, and like the tweets; they can also retweet with comment, which is a popular way of goading followers into directing abuse at someone.

The other potential problem with limited tweets is how its use might affect public figures. Back in 2017, Columbia University's Knight First Amendment Institute sued Donald Trump for blocking Twitter users, and the Court of Appeals last year upheld a ruling against the president, saying that the action was a violation of people's First Amendment rights.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) says public officials using the reply-limiting feature would be violating users' freedom of speech in the same way that blocking them does.

"As a general matter, Twitter's investment in user controls is a good thing. But public officials would be violating the First Amendment if they were to use this tool to block speakers on any accounts they've opened up for public conversation in their roles as government actors. Nor should public officials use this tool to decide who can, or can't, reply to accounts they have opened up for requests for government assistance, which may be on the rise due to COVID-19," wrote the ACLU.