Why it matters: Apple has received a lot of praise for creating the M1 SoC, whether it be for its performance when compared to Intel and AMD CPUs in the same class, or for its relatively cool and battery-friendly operation. However, it's easy to forget the company is able to achieve this partly thanks to being a vertically-integrated hardware company and using that advantage to prioritize responsiveness over raw performance.

This week, rumors emerged about Apple's much-anticipated successor to the M1 chip, which is set to debut later this year in new MacBooks. The upcoming SoC is said to feature a slightly different architecture and could come in two variants aimed at casual and professional users, respectively.

In the meantime, it's worth looking at the reasons why almost everyone buying the new M1-powered Macs is praising them for feeling faster than their Intel-powered counterparts. As you may remember, Apple only showed a few vague graphs comparing performance and efficiency between the M1 and the "latest PC laptop chip," but later those claims were more or less confirmed by independent tests.

Earlier this year, Intel started an all-out ad campaign against M1-powered Macs in an effort to prove they're not as special as you may have heard. Intel's take revolves around being able to play more games on Intel-powered laptops, which also happen to come in a wide variety of form factors, including hybrids between clamshells and tablets that Apple has no intention to build. Intel also hired Justin Long, the "I'm a Mac" actor from Apple's famous "Get a Mac" campaign.

Howard Oakley, a developer behind several Mac applications has done some digging into the magic sauce that makes the M1 chipset so good, and his conclusion may not surprise long-time Apple fans. The short of it is that Apple is optimizing the software experience using Quality of Service, or intelligent task scheduling.

Intel and AMD typically market their products using claims about throughput, or, simply put – the number of operations or tasks that can be completed in a given amount of time. In some scenarios like data centers, that's an easy metric that helps companies decide on the best solution for their needs. However, a consumer usually doesn't perceive the raw speed of a device, but rather latency, something that reviewers often describe as "feeling fast."

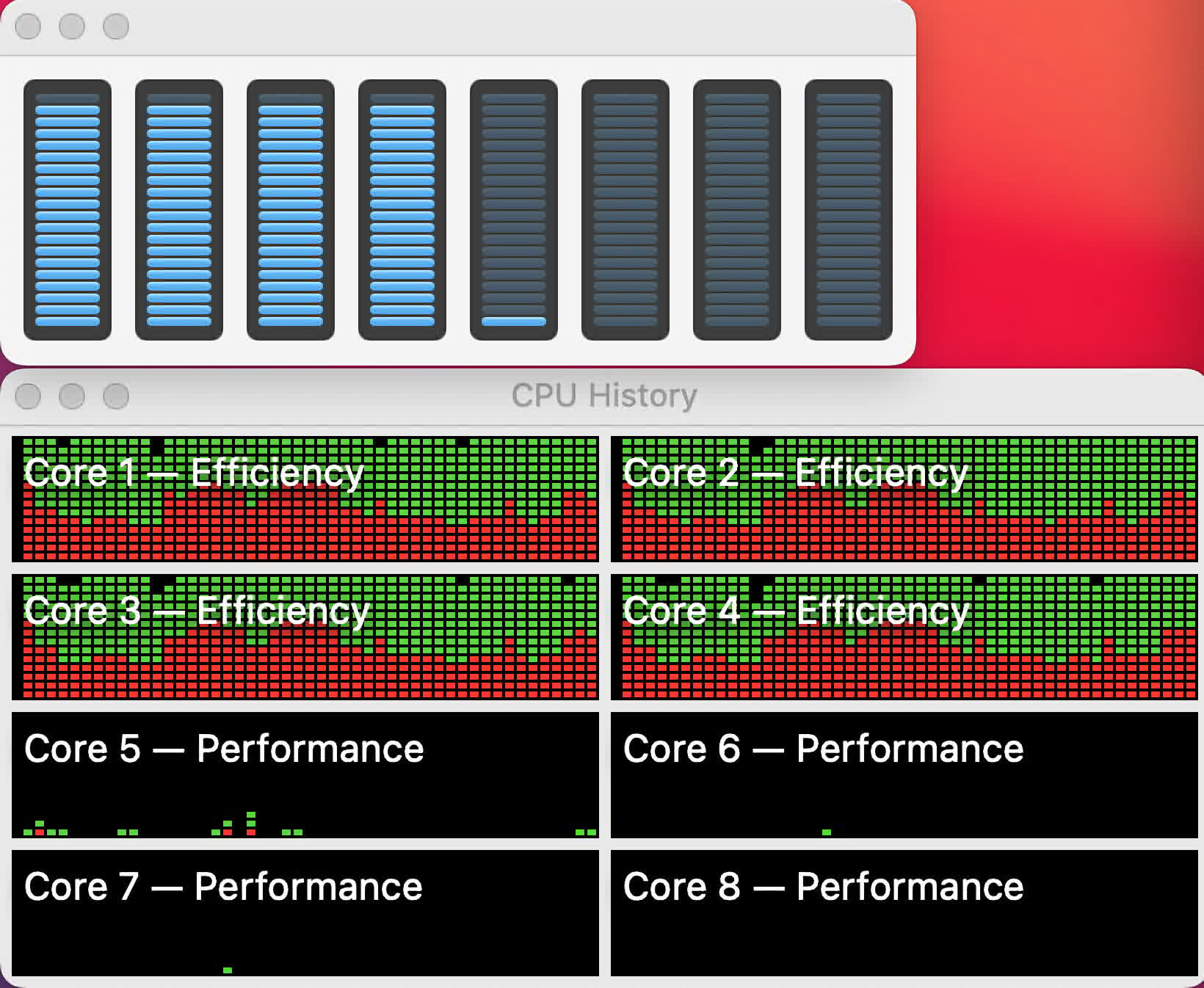

In his analysis, Oakley compared an M1-powered MacBook Pro and Mac mini with an eight-core Intel Xeon-powered Mac Pro, all of them running macOS Big Sur. The idea was to test how these systems behave when you throw tasks of different priority (QoS) levels at them. By default, macOS is set to decide the importance of a task on its own, but developers can also use four specified QoS levels called background (lowest), utility, userInitiated, and userInteractive (highest).

Oakley used his Cormorant app, which is a compressor-decompressor utility that lets you set the QoS level, to compress a 10-gigabyte test file. What he found is that on an x86 Mac with no other apps running, the compression task will be scheduled across all cores, so that it is completed in the shortest possible time, regardless of the QoS setting. When running two compression tasks, one with a high priority level and one with a low level, the first executed in the normal amount of time while the other took several times longer to complete.

By contrast, an M1 Mac behaves quite differently: macOS will schedule a low-priority compression task across the chipset's high efficiency Icestorm cores, even if there's no competing task. This leaves the higher-performing Firestorm cores free to quickly take on higher priority tasks, but has the side-effect of making the compression task slower on the M1 than it would be on Intel-based Mac.

When Oakley set the priority of the compression task to userInitiated or userInteractive, he found that it would get scheduled across all of M1's eight cores. Progressively adding lower-priority compression tasks resulted in them only being allocated to the high efficiency cores and taking virtually the same amount of time as running them sequentially.

What this means is that on the new Macs, Apple prioritizes responsiveness in a similar way as it does on iPhone and iPad. The company has made it so low-priority tasks will always run on the high-efficiency cores and let the high-performance cores stay idle to save power. When you fire up an app, those high-performance cores are ready to execute it with an almost-imperceptible delay, which is why it will "feel faster" than an Intel-based Mac.

Theoretically, Apple could recreate this behavior to some degree on existing Intel-based Macs if it wanted to, by dedicating some processor cores for background tasks and allowing only high priority tasks to run on the remaining cores. This also speaks to Apple's vertical integration where the software is designed to take maximum advantage of the hardware at hand, as well as the willingness of many developers to replicate its approach when designing their apps.

Many tech companies routinely look at Apple for a sense of direction, so we'll probably see similar optimizations on Windows in the near future. Last year, someone proved an ARM64 build of Windows 10 ran better in a virtual machine on the M1-based Macs than it did on Microsoft's Surface Pro X, even though the latter is equipped with a Snapdragon 8cx SoC with a similar configuration of four high efficiency cores and four high performance cores.

Intel's upcoming Alder Lake CPUs could be the first x86 chips to feature a big.LITTLE architecture, assuming they land in desktop PCs by the end of this year, as promised. These will feature a combination of low-power Gracemont cores and high performance Golden Cove cores built on the company's 10 nm SuperFin process node, which hopefully means they'll be pretty power-efficient even when fully-stressed.

Power consumption will be an important selling point as it will no doubt draw comparisons to that of the Apple M1 SoC, which is up to three times more efficient that the Intel processors it replaced.

AMD could follow in Intel's footsteps with Zen 5, too, which is said to feature eight high performance x86 cores and eight high efficiency x86 cores. The company is even exploring the idea of making a direct, Arm-based competitor to the Apple M1 that could come with integrated RAM, but details on that project are still scarce. Even Microsoft is cooking up a similar concept for its future Surface PCs and Azure servers, so there are exciting times ahead of us.