I've spent a long time trekking across Far Cry 5's fictional Hope County, Montana fighting the members of an apocalyptic cult led by a man called Joseph Seed, and I'm still not sure what their deal is. They drive around blasting weird Christian synth and shooting non-members on sight. It's weird and terrifying and unsatisfyingly explored in this epic-length game. For all its nods to contemporary politics and societal strife, Far Cry 5 is just another fun permutation of the usual Far Cry formula with nothing very interesting to say.

I've spent a long time trekking across Far Cry 5's fictional Hope County, Montana fighting the members of an apocalyptic cult led by a man called Joseph Seed, and I'm still not sure what their deal is. They drive around blasting weird Christian synth and shooting non-members on sight. It's weird and terrifying and unsatisfyingly explored in this epic-length game. For all its nods to contemporary politics and societal strife, Far Cry 5 is just another fun permutation of the usual Far Cry formula with nothing very interesting to say.

Ubisoft's latest open-world first-person shooter depicts a society on the edge from the point of view of a small midwestern town cut off from the rest of the country. Creative director Dan Hay has said as much in interview after interview, stemming, he's said, from anxiety following the financial crisis of the last decade. The game does try to clumsily tap into a pervasive sense in the real world that something's got to give. In the game, we've got heavily armed Americans beginning to fight back against other heavily armed Americans. In real life, we've got Neonazis and Antifa brawling, endless polarization by the United States' major political parties, worsening climate change and a dotard wandering the White House with access to the launch codes. Far Cry 5's sense of the end times thus has a ring of truth to it, but the game has no idea where to take things from there.

Also read...

Far Cry 5 Benchmarked: 50 GPUs Tested

The game plays well, with you in the role of unnamed deputy (male or female, in a series first) fighting back against the cult. Its depiction of a growing resistance makes for a compelling mission flow, but it does a terrible job of integrating the extreme violence that makes it all work with the believable community of diverse individuals you spend the game getting to know. Far Cry stories have never lived up to their premise. Take the idea of a spoiled 20-something becoming a deadly killer overnight in Far Cry 3. That missed potential hits hardest with Far Cry 5. Joseph Seed is supposed to be a charismatic cult leader taking in those who feel alienated and left behind. At no point, however, did his supposed appeal come through in the game. He did not evoke the charisma of, say, the cult leader David Koresh, as played by Taylor Kitsch in the recent Waco miniseries that retold the infamous 51-day siege of a religious compound in Texas in 1993. For all his talk of economic anxiety and attempts to offer an alternative to the turmoil of modern politics, Seed's arrival in Hope County and subsequent reign are fueled only by violence and fear. One of the game's first characters, a Vietnam veteran named Dutch, is praised by others in the game as being one of the first to see through Joseph's rhetoric. I can't help but wonder what gave it away: the public displays of mutilated bodies crucified with rebar or the hordes of wandering "angels," cultists who overdosed on Bliss and now have a penchant for bludgeoning people to death.

It would be easier to forgive the game's glib cartoonishness if it weren't for all the work it does trying to invite comparisons to contemporary America real world. The game is keen to gesture whenever it can to America's current political moment.The cigar smoking, rifle-cradling conservative Hurk Drubman Sr. (father to the long-running Far Cry character of the same name) asks you to help his campaign for state office by suppressing the vote. One of Joseph's brothers, Jacob, is messed up from seeing wolves eat his buddy while lost in the desert during the first Gulf War. The game depicts an America infatuated with guns, a theme that proves disturbingly current. At the same time that the cultists worship at church armed to the teeth, there was an actual cult blessing their AR-15s weeks after one was used to commit a mass school shooting. Joseph's sermons, played on the radio and on TV broadcasts, talk about the failure of politicians to fix what's wrong with the country and the need to look inward for meaning in a world that cares only about profit. If the cult were real, Wolf Blitzer would have already interviewed its leader twice.

All of the games allusions to real American problems, along with the generally mind-bending psychopathy of the cult, are at odds with the majority of what you see, hear and do in the game, the further you get from its cutscenes. The bulk of Far Cry 5 feels like gonzo camping trip that permeates the rest of the game. Yes, people are being kidnapped, tortured, and brainwashed, but in-between fighting to liberate the residents of Hope County from this b-horror movie plot, I also spent plenty of time skydiving, swimming, hiking, hunting, fishing, and rampaging through cedar forests on 4-wheelers at night like an idiot. I'd like to say this mix of the Huffington Post front page and a Bass Pro Shop catalog ends up being complementary, but it doesn't work, with the split between ominous main plot and absurd side adventures feeling even more dissonant than in earlier Far Cry games. Far Cry 5 doesn't have warring political factions or a well-defined protagonist's descent into madness to help anchor its gamey patchwork of interlocking systems and over the top caricatures. There's just you, a sheriff's deputy with no backstory, motivation, or emotions of her own, negotiating one disorienting swing from hyper violence to charming absurdity after another.

Away from the main plot and if you can ignore the potential for greater thematic complexity the setting presented, Far Cry 5 actually shines.After the opening cinematics and a short stint on a small tutorial island, the entirety of Hope County opens up. Recent Far Cry environments have been tropical, Himalayan or prehistoric. Far Cry 5's are pedestrian North American landscapes full of pine forests, tall mountain ranges, and flat farmlands carved up by clear, winding rivers.

This map, which publisher Ubisoft claims convincingly is bigger than any of the previous Far Cry games, is sliced into three regions, each controlled by one of Joseph's siblings who you must assassinate in order to get to him. Doing so requires building up a "resistance meter" for each region by completing missions, rescuing hostages, and blowing up buildings controlled by Peggies (what locals have lovingly nicknamed the worshippers of the Seed's cult, the Project at Eden's Gate). Filling up meters might sound boring, but here they're a revelation. Instead of needing to follow a crumb trail of main story quests constantly bringing you into contact with Joseph you can effectively do whatever you want and have it contribute to the overall resistance effort. It's a license to go out, explore, and have weird things happen free from the narrative constraints that bound previous games.

"Near death and sprinting---a condition I've spent at least half of Far Cry 5 in."

Your map of the area starts off mostly shrouded in fog. As you explore more of it, collect maps, and complete objectives, sections fill in. You'll learn, for example, that between these two hills is a person's house and across the river is a gas station that needs to be liberated from cultists and converted into a place where you can shop for guns, cars, and helicopters. Re-capturing a landmark generally reveals characters who will offer new missions for you. Distractions are constant. A character may ask you to steal back their beloved semi-truck from enemy hands or find a missing pet mountain lion, and just as they end their sentence, a Peggie truck oil tanker may drive by. Blowing it up will help the resistance, so off you go. Once you've apprehended the vehicle, killed the driver, and either destroyed or looted it, you might even hear a cry for help from farther down the road or somewhere off into the woods. Two Peggies are proselytizing at someone tied up beside them, so you pick them off quickly with a couple of headshots, untie the person, and lo and behold they heard that their friend Hank who lives just down the road is about to get raided and so now you have to go check that out too.

This is how missions cascade in Far Cry 5, all of which can be played in full co-op online, including the main story, a first for the series (although story progress only counts for the hosting player). Sometimes missions emerge conventionally. A named character asks you to go to a marker on your map and kill or bring back whatever's there. Other times the missions seem to arise by accident. The game's quest-givers, like its enemy patrol cars and emergent wildlife, tend to show up when you aren't looking, rather than being pegged to specific locations.

Then there are the infamous Far Cry anecdotes, a storytelling genre unto themselves, in which otherwise common game activities like killing everyone you see and blowing shit up lead to unpredictable outcomes. What had previously just been another side mission to check off of a list is transformed into something special, in part because it was somehow the culmination of events you the player set in motion. Far Cry 5 has those too, but its wide range of independent characters augments them in interesting ways.

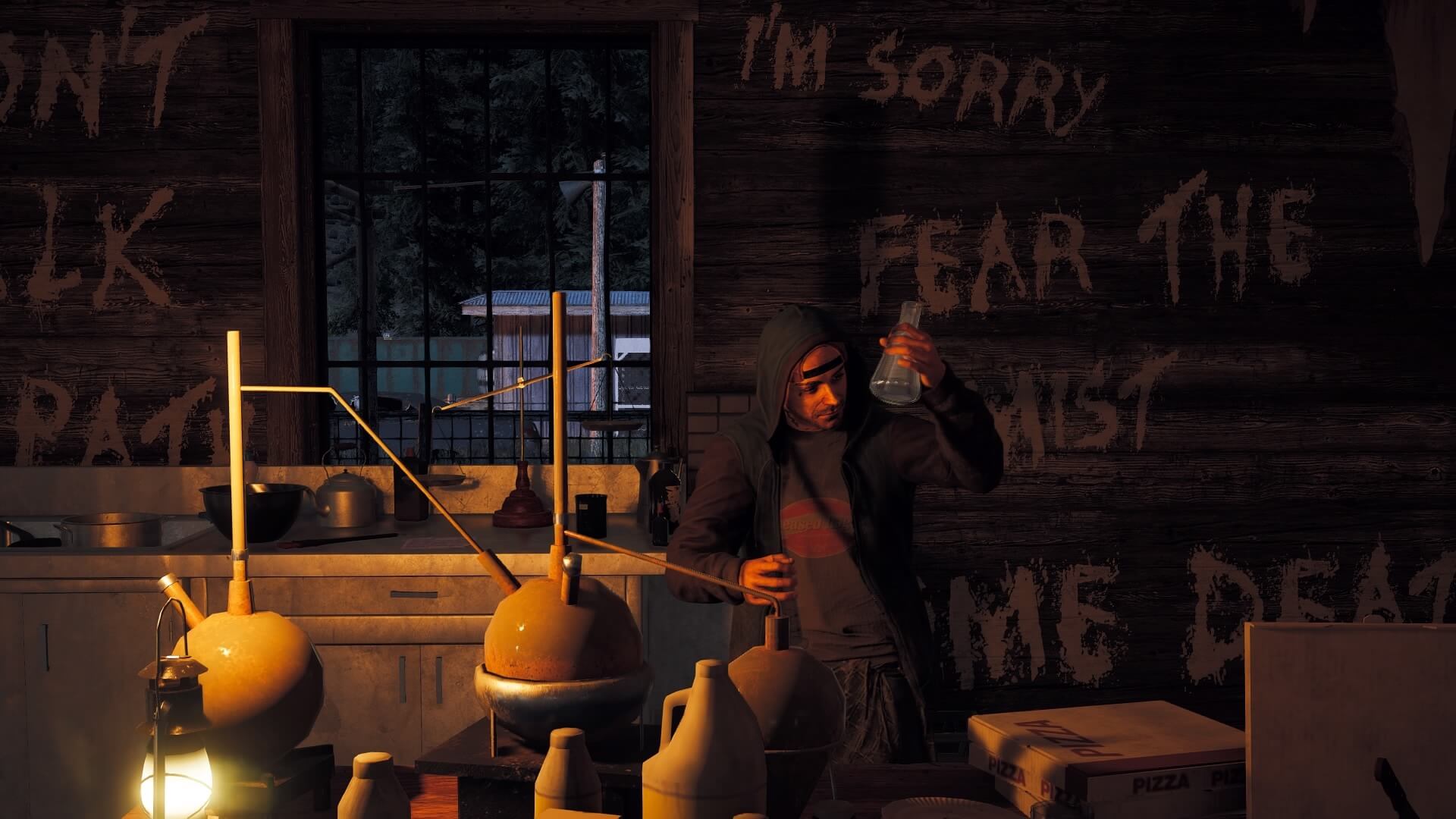

One night my character was getting bombed out of her mind in an abandoned campground turned drug lab on the southeastern edge of the map. An addict named Tweak was teaching me how to make "homeopathics," the game's potions, which included consuming them. In the middle of our research a plane started dropping bombs outside our cabin. Understandably freaked out, Tweak looked for cover in a shrub outside while I tried, my character's vision blurred and motor functions impaired, to snipe the plane's pilot from the ground. This was unsuccessful. Then trucks full of cultists pulled up at the entrance to the grounds, one with a mounted gun fixed on my my location.

Near death and sprinting---a condition I've spent at least half of Far Cry 5 in---I climbed onto the roof of one of the buildings, aimed at the plane as it bore down on me for another strike, and chucked a stick of dynamite. Seconds later an explosion lit up the night sky. Another followed as the flaming wreckage slammed straight into armed convoy that had just shown up. It was a great Far Cry moment.

As unwanted as the initial encounter was it ended up blossoming into something memorable, at least for me if not Tweak, my comrade who was happy to pick up our business exactly where it had left off. This kind of thing happened in other Far Cry games, too, but in this one it happens around characters I grew to care about. I like Tweak. He is weird. He lives in a hangout filled with mannequins posed just like people who once resided there. The walls of his lab are lined with phrases like "He lied!" and "I'm sorry!" scrawled in chalk. It's creepy, as is Tweak's upbringing, which unsent letters to his father will attest, but he's turned to concocting medicinals to try and combat the effects of the Bliss on the community. I've been harassed by countless planes and helicopters while playing this Far Cry game, often out of the blue, but the ensuing firefights became a part of something much more interesting when they inevitably happened around characters I had learned to care about.

There are limits to these interactions, and this is where Far Cry 5 shows its shortcomings.

Far Cry 5's hired gun system, one that's been evolving since Far Cry 2 and now includes animals like in Far Cry Primal, plays a big part in forging these connections to characters. There are nine major human or animal characters you can befriend and invite with you on missions, each with unique attributes. They range from a dog who can spot and fight enemies to a chatty pilot who provides air support. In addition, randomly generated characters you encounter in the world can be hired, though they're not as useful and have less interesting things to say while traveling with you.

At a basic level, it's great to be trying to take down an enemy outpost and have someone watching your back who can revive you and also take out enemies you highlight with the direction pad. The system works flawlessly. There's also an upgrade that allows you to bring two companions at a time, allowing you more avenues of attack and also providing an incentive to play the game on hard to keep things interesting. In terms of the game's emergent story, however, having these hired guns also helps you build relationships beyond the original missions in which you met them. When I first encountered Jess Black, she was trying to get revenge on a cannibal, several hours later she's saved my neck more times then I can count and her macabre personality seems a good fit for the carnage we witness together.

There are limits to these interactions, and this is where Far Cry 5 shows its shortcomings in significantly evolving beyond its aging formula. Sure, these buddies seem more sentient than the average Far Cry character, but most of the people in this game world seem exceedingly clueless. Despite the atrocities going on around them, Hope County's residents remain mostly chipper and good natured. This resilience often feels uplifting and humanizing. When I'm methodically skinning bears and mistakenly shooting civilians though, their continued solidarity and obliviousness of most of the game's characters wears thin. Blowing up a van of prisoners invites a stern warning from the game not to kill innocents, but my neighbors barely react and don't hold grudges long. Hired guns can be downed but they're never out for long. One time I accidentally lit Jess on fire. She screamed in pain one moment, but was soon thanking me profusely when I revived her. At times like these, the game's characters are more like the mannequins at Tweak's campsite than believable people.

The game has a streamlined player progression system that lets players unlock abilities by doing basic challenges like getting a set number of shotgun kills or gliding with the wingsuit for a specific length. The system is functional but short-lived and limited. One challenge involved killing and skinning five bison, so, in the interest of gaining more perks, I looked across my map for bison. My map had a marker for bison ever since I'd collected a magazine in a bunker nearby. (Like just about everything in the game, from cult outposts to neighbors houses, hunting sites only appear as such once you've discovered them yourself or found a collectible noting the location.) I would find the bison in a field just off the side of the road next to a river. I pulled out my .50 caliber and got to work. Two shots a piece. Of all the game's varied wildlife, the bison are some of the easiest to kill. A wolverine hiding in the tall grass nearby caused more trouble than all of them combined.

Unlike in previous games, animal parts aren't used for crafting in Far Cry 5. Instead, gun enhancements are bought outright, and animal skins are collected to satisfy the requirements of specific quests or just sold for cash. I killed a lot of animals in the game, as is par for the course in every Far Cry. In Far Cry 5, however, it's connection to American outdoorsmanship somehow makes it feel more self-indulgent and evil. After all, here I am with military-grade weapons bringing to the ground with relative ease not just one or two but eight bison and counting. I got three more than I needed because even though the pained groans of a bison are unsettling, their hides fetch $200 a piece and the 1911 Extended pistol I'd been coveting costs a small fortune.

Nearly every corner of Hope County oozes a sense of patriotic bravado.

After skinning their corpses, I saw some camping equipment not far off by a downed tree. There I found a small abandoned backpack, toolbox, and cooler upon which sat a note, from no one in particular, which read: "A baby bison is called a 'red dog' because the people who name things lack basic education. Also, humans slaughtered 50 million of them. 50 MILLION!" With one cutting bit of flavor text the game made me feel like an asshole for trying to use the systems it had put in place to develop my character. It also hinted at a legacy of real world violence the game is content to mine for moral significance and weight without doing much to tackle it head on. No one in Hope County will pop out of the woods to chastise you for poaching or call your methods into question. Violence is simply the way of things, and as in past games, Far Cry 5 isn't interested in calling that into question beyond the occasional subtext or poorly conceived monologue spoken by someone with no room to point fingers.

On January 23, 1870, Colonel Eugene Baker led a raid on a camp of Blackfeet Native Americans in Northern Montana. His soldiers killed some 37 men, 90 women, and 50 children for, admittedly, no reason other than that the Montanans were afraid of them. Now dubbed the Marias Massacre, The New York Times called it a "shocking affair" at the time, while the New North-West of Deer Lodge, Montana countered that these critics were simply "namby-pamby, sniffling old maid sentimentalists." While the occasional note in Far Cry 5 might grapple with this past, the game's characters refrain from engaging in complex debates around American history, gun culture or religious fundamentalism. It would have been a richer game if it at least mined its setting for more than cultural knick-knacks designed to be the butt of some joke.

Nearly every corner of Hope County oozes a sense of patriotic bravado, only this time it's aimed, barrels loaded, at a sect of religious extremists. Notably, hardly anyone ever talks about trying to persuade some of the cultists to leave Joseph's "flock," and there's no way to capture or subdue any of them. Every attack is lethal. This, I suspect, is partly why Bliss figures so heavily into the lore of the cult and what they derive their power from. It helps erase any ethical gray area. Racial tensions, sexism, and actual political disagreements are similarly paperped over in the game. Everyone in Hope County who isn't a Peggie gets along fine for the most part, making it even more unbelievable that a death cult would have found it so easy to take root their in the first place. Where Joseph's apocalypticism offers an obvious opportunity to dig further into the actual political divisions which might afflict place like Hope County, Far Cry 5 uses it mostly for ominous effect and narrative head-fakes.

Early on I thought Far Cry 5 might actually plan on grappling with these demons, the ones its villains seem engineered to manifest in uniquely American ways. Maybe Joseph and the Peggies were symbolic of some sort of punishment for the country's larger failings beyond Hope County. The more I played, though, the more I realized that's not the case. Far Cry 5 is a flashier iteration of the past games whose newfound relationship to reality is really just another sideshow.

"I could play this all day," characters standing over the machines say, despite the gunships constantly flying overhead.

One of the main attractions, long term at least, is likely to be the game's Far Cry Arcade. It offers a more robust level editor than past games which you could spend hours sinking time into constructing maps and missions to be shared with other players online. Perks, items, and cash you earn during these missions carry over into the main game, and although the existing Ubisoft ones are vanilla at the moment, I'm confident players will eventually construct custom death traps even better than what's in the main game, not to mention whenever the Far Cry: Battle Royale mode inevitably arrives. It's a development that fits in perfectly with Ubisoft's games-as-service strategy, but one that only further dilutes the impact and weight of the game's main story. Arcade machines and posters throughout the world invite you to go play the game's eccentric multiplayer stuff. "I could play this all day," characters standing over the machines say, despite the gunships constantly flying overhead.

Far Cry games are laboratories for experimenting, giving you the freedom to do stuff ordinary games won't, like throw a molotov cocktail at just about anything and watch it burn to the ground. They usually have better shooting than most open world games, and better open worlds than most shooters. Far Cry 5 nails that part of the series' legacy. The game's missions flow together organically and let you shift from capturing a cult outpost using an array of explosives and guns to scaling cliffs in search of hidden caches of equipment and lore-filled collectibles. It fails, however, to meaningfully move beyond the rest of the series in merging the violence and chaos these experiments produce with the community of people scattered throughout its world. These are still silly worlds full of silly people and no amount of gravitas about the world being on the edge can be sustained in a game that so frequently sends you into hunts for cow testicles or stunt races set to the theme song of a retro daredevil. The series has always struggled with this dichotomy. It's only fitting that after several games subjecting fictional populaces from the global south to this confusion it arrives in America's backyard. The boldness of this decision, however, isn't backed up by the lackluster story or simplistic fight for liberation taking place on the ground.