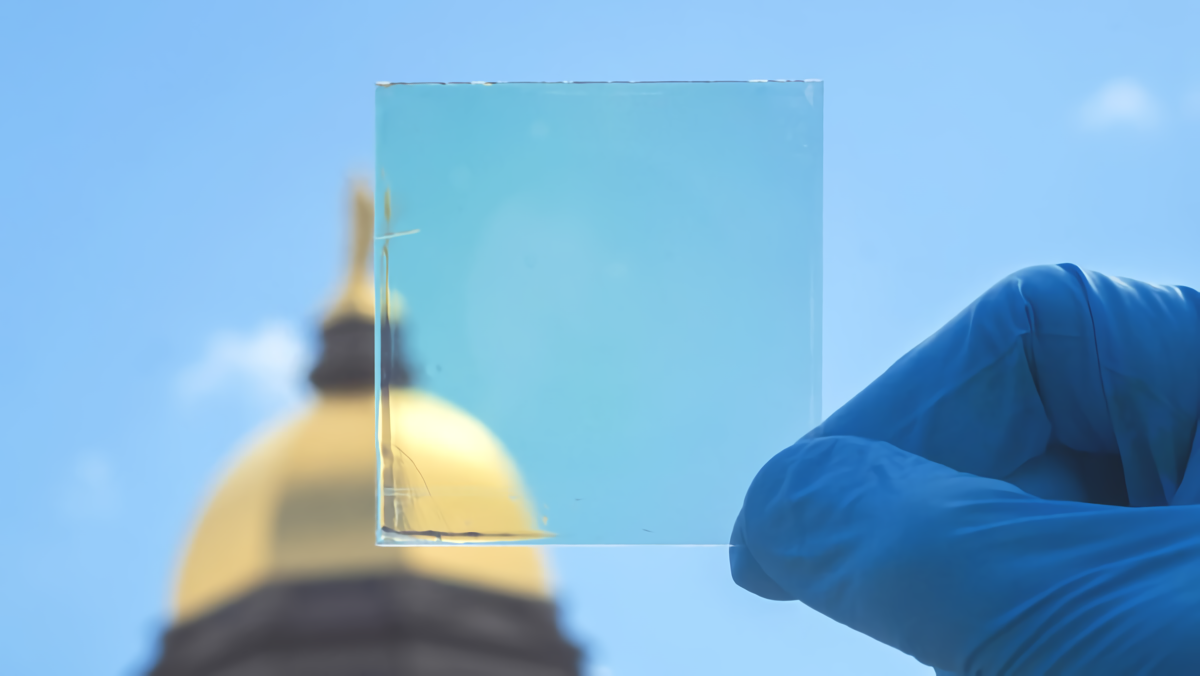

In brief: Researchers from the University of Notre Dame have developed a new window coating that promises to block heat-generating infrared and ultraviolet light while allowing visible light to pass unimpeded. The coating could reduce air-conditioning costs in warm climates by more than a third, all without compromising the view.

Sun blocking window film and coatings have been around for decades, but they are not all created equal. Many are designed to work best when light enters at a 90-degree angle but in the real world where the angle is constantly changing due to the position of the Sun in the sky, effectiveness can vary.

Professor Tengfei Luo and his postdoctoral associate Seongmin Kim previously developed an ultra-thin window coating by stacking layers of silica, alumina, and titanium oxide onto a glass base. A silicon polymer, like what is used on contact lenses, was also added to enhance its cooling abilities.

The order of the layers played a key role in the coating's capabilities. To find the optimal configuration, Luo and Kim needed to test every possible arrangement. This wasn't practical in the real world due to the sheer number of possible combinations, so they turned to tech - quantum annealing, to be exact.

The end result was a 1.2 micron-thick coating that is said to outperform all other heat-reducing glass coatings on the market. In testing, their solution was able to reduce room temperature by 5.4 – 7.2 degrees Celsius.

Luo likened the coating to polarized sunglasses in that they lessen the intensity of incoming light. Unlike sunglasses, however, Luo said their coating remains clear and effective even when you tilt it at different angles. Best yet, the coating can be applied retroactively to existing windows and even be used on automobile glass. The quantum annealing test approach, meanwhile, can be adapted to help design other materials with complex properties.

The team's research has been published in Cell Reports Physical Science. No word yet on commercial availability.

Image credit: Scott Webb

Cool and clear: New window coating blocks heat-generating UV rays without sacrificing clarity