Ever since the case of the San Bernadino shooter pitted Apple against the FBI over the unlocking of an iPhone, opinions have been split on providing backdoor access to the iPhone for law enforcement. Some felt that Apple was aiding and abetting a felony by refusing to create a special version of iOS with a backdoor for accessing the phone’s data. Others believed that it’s impossible to give backdoor access to law enforcement without threatening the security of law-abiding citizens.

In an interesting twist, the battle ended with the FBI dropping the case after finding a third party who could help. At the time, it was theorized that the third party was Cellebrite. Since then it has become known that Cellebrite— an Israeli company—does provide iPhone unlocking services to law enforcement agencies.

Editor’s Note:

Guest author Thomas Reed is a self-trained Apple security expert. He was CEO of The Safe Mac, developer of AdwareMedic, before joining Malwarebytes as Director of Mac & Mobile. This post was originally published on the Malwarebytes Labs Blog. Republished with permission.

Cellebrite, through means currently unknown, provides these services at $5,000 per device, and for the most part this involves sending the phones to a Cellebrite facility. (Recently, Cellebrite has begun providing in-house unlocking services, but those services are protected heavily by non-disclosure agreements, so little is known about them.) It is theorized, and highly likely, that Cellebrite knows of one or more iOS vulnerabilities that allow them to access the devices.

In late 2017, word of a new iPhone unlocker device started to circulate: a device called GrayKey, made by a company named Grayshift. Based in Atlanta, Georgia, Grayshift was founded in 2016, and is a privately-held company with fewer than 50 employees. Little was known publicly about this device—or even whether it was a device or a service—until recently, as the GrayKey website is protected by a portal that screens for law enforcement affiliation.

According to Forbes, the GrayKey iPhone unlocker device is marketed for in-house use at law enforcement offices or labs. This is drastically different from Cellebrite’s overall business model, in that it puts complete control of the process in the hands of law enforcement.

Thanks to an anonymous source, we now know what this mysterious device looks like, and how it works. And while the technology is a good thing for law enforcement, it presents some significant security risks.

How It Works

GrayKey is a gray box, four inches wide by four inches deep by two inches tall, with two lightning cables sticking out of the front.

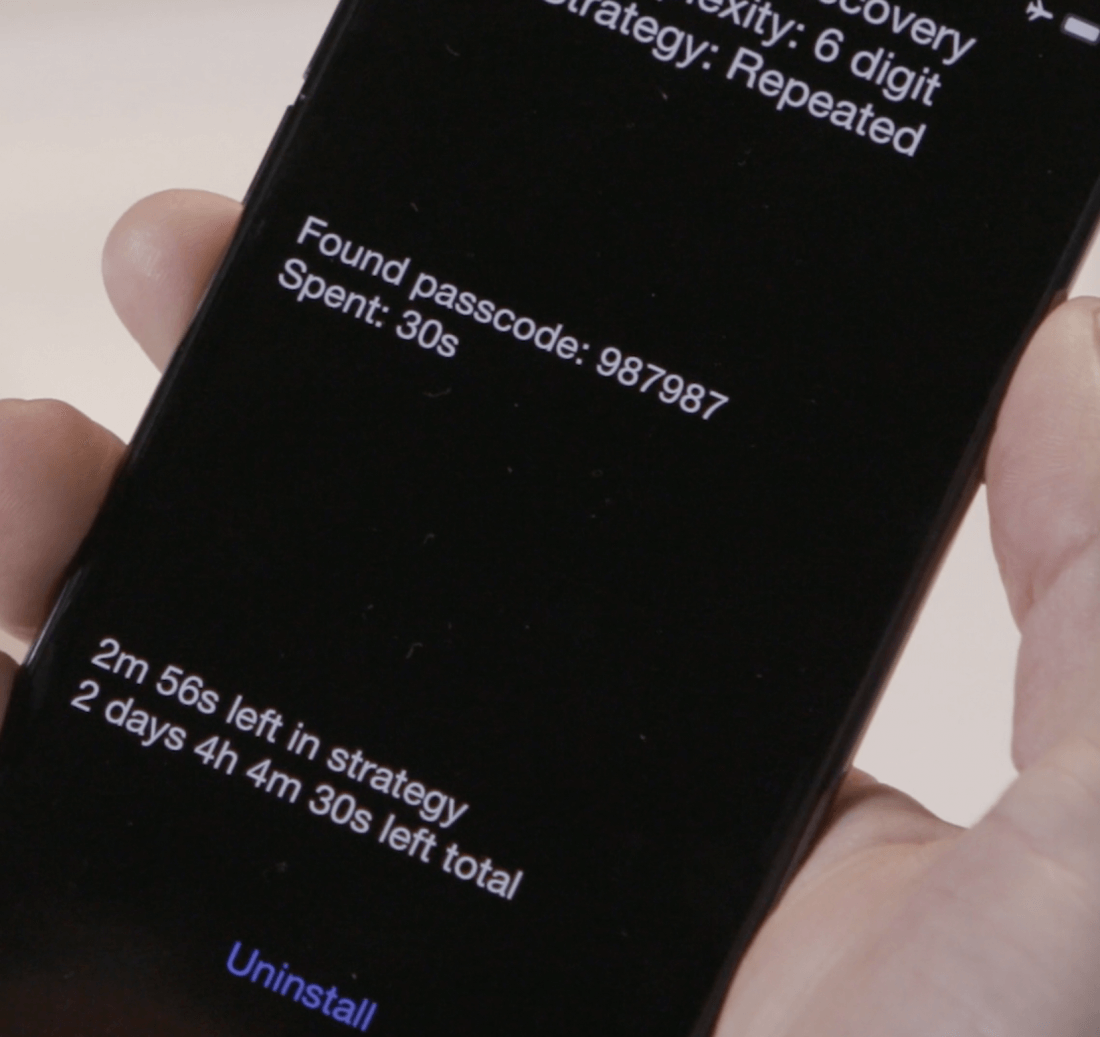

Two iPhones can be connected at one time, and are connected for about two minutes. After that, they are disconnected from the device, but are not yet cracked. Some time later, the phones will display a black screen with the passcode, among other information. The exact length of time varies, taking about two hours in the observations of our source. It can take up to three days or longer for six-digit passcodes, according to Grayshift documents, and the time needed for longer passphrases is not mentioned. Even disabled phones can be unlocked, according to Grayshift.

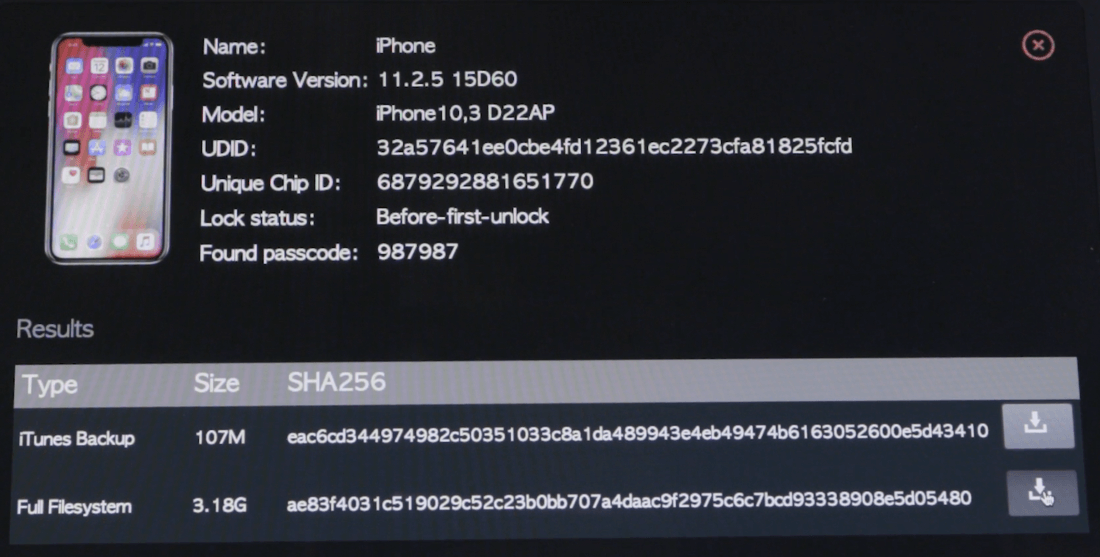

After the device is unlocked, the full contents of the filesystem are downloaded to the GrayKey device. From there, they can be accessed through a web-based interface on a connected computer, and downloaded for analysis. The full, unencrypted contents of the keychain are also available for download.

As can be seen in the screenshot above, the GrayKey works on the latest hardware, and at least on iOS up to 11.2.5 (which was likely the most current system at the time this image was captured).

The GrayKey device itself comes in two “flavors.” The first, a $15,000 option, requires Internet connectivity to work. It is strictly geofenced, meaning that once it is set up, it cannot be used on any other network.

However, there is also a $30,000 option. At this price, the device requires no Internet connection whatsoever and has no limit to the number of unlocks. It will work for as long as it works; presumably, until Apple fixes whatever vulnerabilities the device relies on, at which time updated phones would no longer be unlockable.

The offline model does require token-based two-factor authentication as a replacement for geofencing for ensuring security. However, as people often write passwords on stickies and put them on their monitors, it’s probably too much to hope that the token will be kept in a separate location when the GrayKey is not being used. Most likely, it will be stored nearby for easy access.

Implications

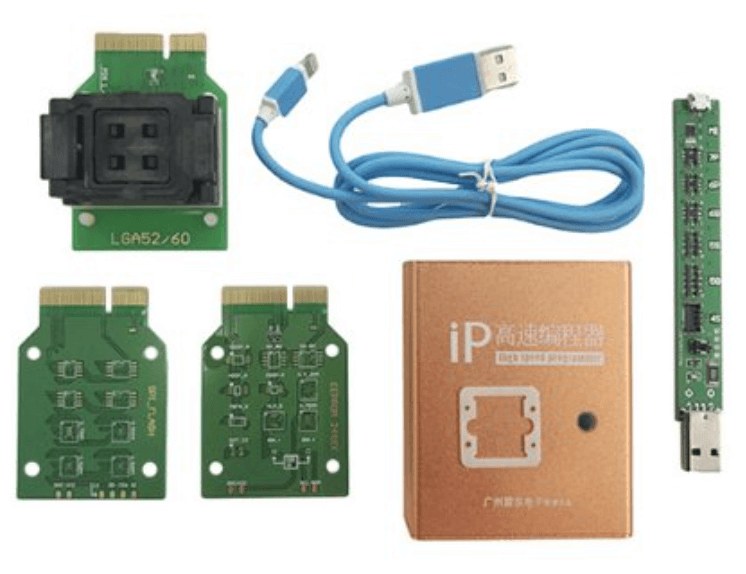

For law enforcement, this is undoubtedly a boon. However, historically, similar stories involving cracking the iPhone haven’t turned out so well. Consider, for example, the case of the IP-Box, a similar device that was once used to access the contents of iPhones running older versions of iOS. The utility of the original IP-Box ended in iOS 8.2, which gave rise to the IP-Box 2.

Unfortunately, the IP-Box 2 became widely available and was almost exclusively used illegitimately, rather than in law enforcement. Today, various IP-Boxes can still be found being sold through a variety of websites, even including Amazon. Anyone who wants such a device can get one.

What happens if the GrayKey becomes commonplace in law enforcement? The cheaper model isn’t much of a danger if stolen—unless it’s stolen prior to setup—but at 4″x 4″x 2″, the unlimited model could be pocketed fairly easily, along with its token, if stored nearby. Once off-site, it would continue to work. Such a device could fetch a high price on the black market, giving thieves the ability to unlock and resell stolen phones, as well as access to the high-value data on those phones.

Worse, consider the implications of what is done to the phone itself. It is currently not known how the process works, but it’s obvious there is some kind of jailbreak involved. (A jailbreak involves using a vulnerability to unlock a phone, giving access to the system that is not normally allowed.) What happens to the device once it is released back to its owner? Is it still jailbroken in a non-obvious way? Is it open to remote access that would not normally be possible? Will it be damaged to the point that it really can’t be used as intended anymore, and will need to be replaced? It’s unknown, but any of these are possibilities.

We also don’t know what kind of security is present on the networked GrayKey device. Could it be remotely accessed? Could data be intercepted in transit? Is the phone data stored on the device strongly encrypted, weakly encrypted, or is it not even encrypted at all? We don’t know.

Most people probably won’t get too excited about a criminal’s phone or data. However, let’s keep in mind one of the fundamental principles of the US judicial system: suspects are innocent until proven guilty. Should suspects be susceptible to these kinds of searches by law enforcement?

Further, not all phones analyzed by law enforcement belong to suspects. In one digital forensics lab in 2014, around one-third of the devices analyzed were given to the authorities with explicit consent, by alleged victims or witnesses, to assist in the investigation. In such cases, a passcode would likely be given, but it’s possible it didn’t get passed on to the forensic technician. It’s also possible the technician may prefer to use the GrayKey to analyze the device regardless of availability of the passcode, due to the copious amounts of data it can generate from the device.

This means that many innocent people’s phones will end up being analyzed using a GrayKey device. What happens if their phones are given back in a vulnerable state, or their data is handled insecurely? That is not only a threat to the individual, but a liability for the police.

Who Should We Trust?

For most people in the US, law enforcement agents are people to be trusted. Obviously, this can’t be true in all cases, people being people, but let’s start from that assumption. Unfortunately, even if the agents themselves are completely trustworthy, sources in law enforcement have said that the computer systems used by law enforcement in the US are often quite poorly secured. Is it a good idea to trust sensitive data, some of which will come from the phones of innocent US citizens, to insecure systems?

Little is known about Grayshift or its sales model at this point. We don’t know whether sales are limited to US law enforcement, or if it is also selling in other parts of the world. Regardless of that, it’s highly likely that these devices will ultimately end up in the hands of agents of an oppressive regime, whether directly from Grayshift or indirectly through the black market.

It’s also entirely possible, based on the history of the IP-Box, that Grayshift devices will end up being available to anyone who wants them and can find a way to purchase them, perhaps by being reverse-engineered and reproduced by an enterprising hacker, then sold for a couple hundred bucks on eBay.

An iPhone typically contains all manner of sensitive information: account credentials, names and phone numbers, email messages, text messages, banking account information, even credit card numbers or social security numbers. All of this information, even the most seemingly innocuous, has value on the black market, and can be used to steal your identity, access your online accounts, and steal your money.

The existence of the GrayKey isn’t hugely surprising, nor is it a sign that the sky is falling. However, it does mean that an iPhone’s security cannot be ensured if it falls into a third party’s hands.

https://www.techspot.com/news/73786-graykey-iphone-unlocker-poses-serious-security-concerns.html