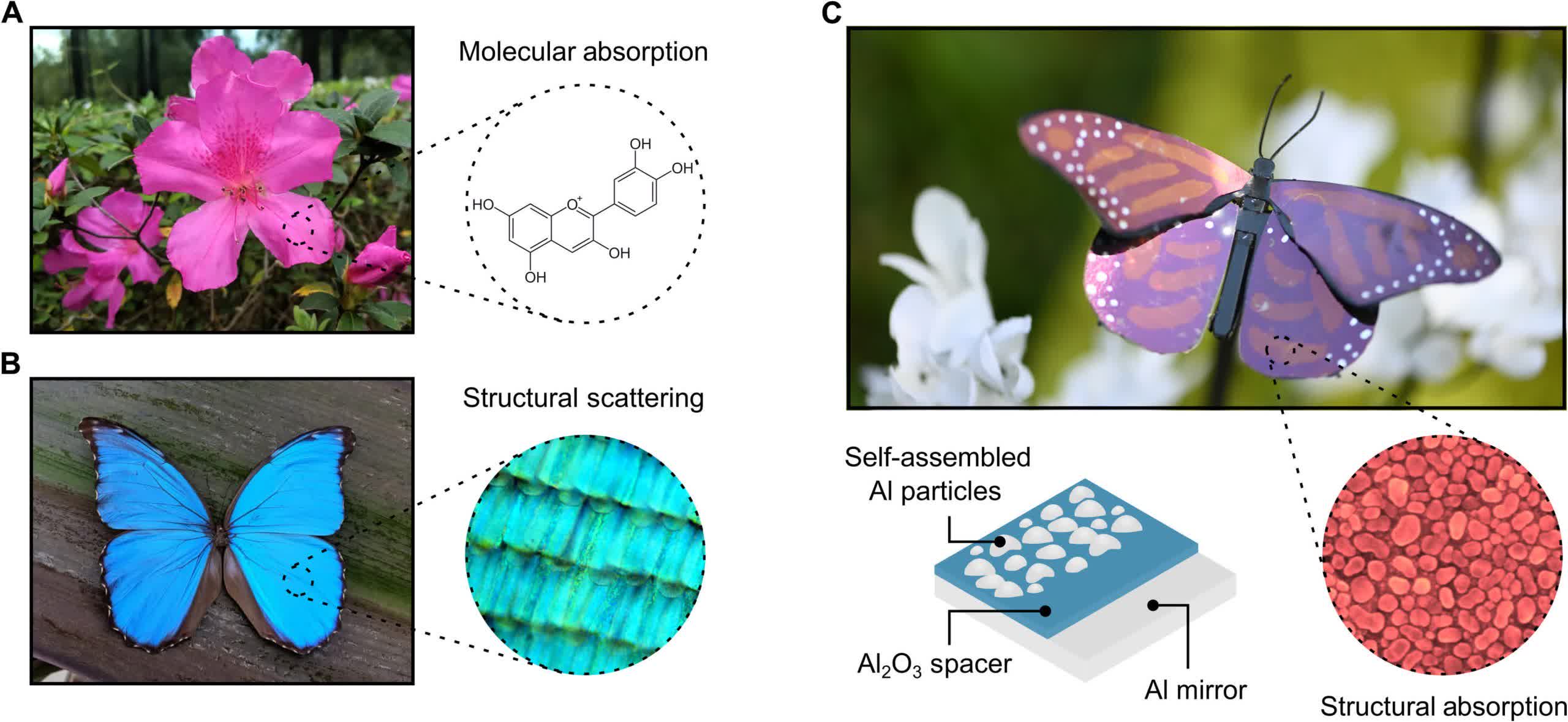

Yeah! Science! Traditional paint is made from a bonding agent, such as oil, and pigments from heavy metals like cobalt, ochre, and cadmium, which make blue, red, and yellow, respectively. We use paint to color the artificial world, but in nature, creatures such as butterflies and beetles display vibrant palettes without pigment – they use topography.

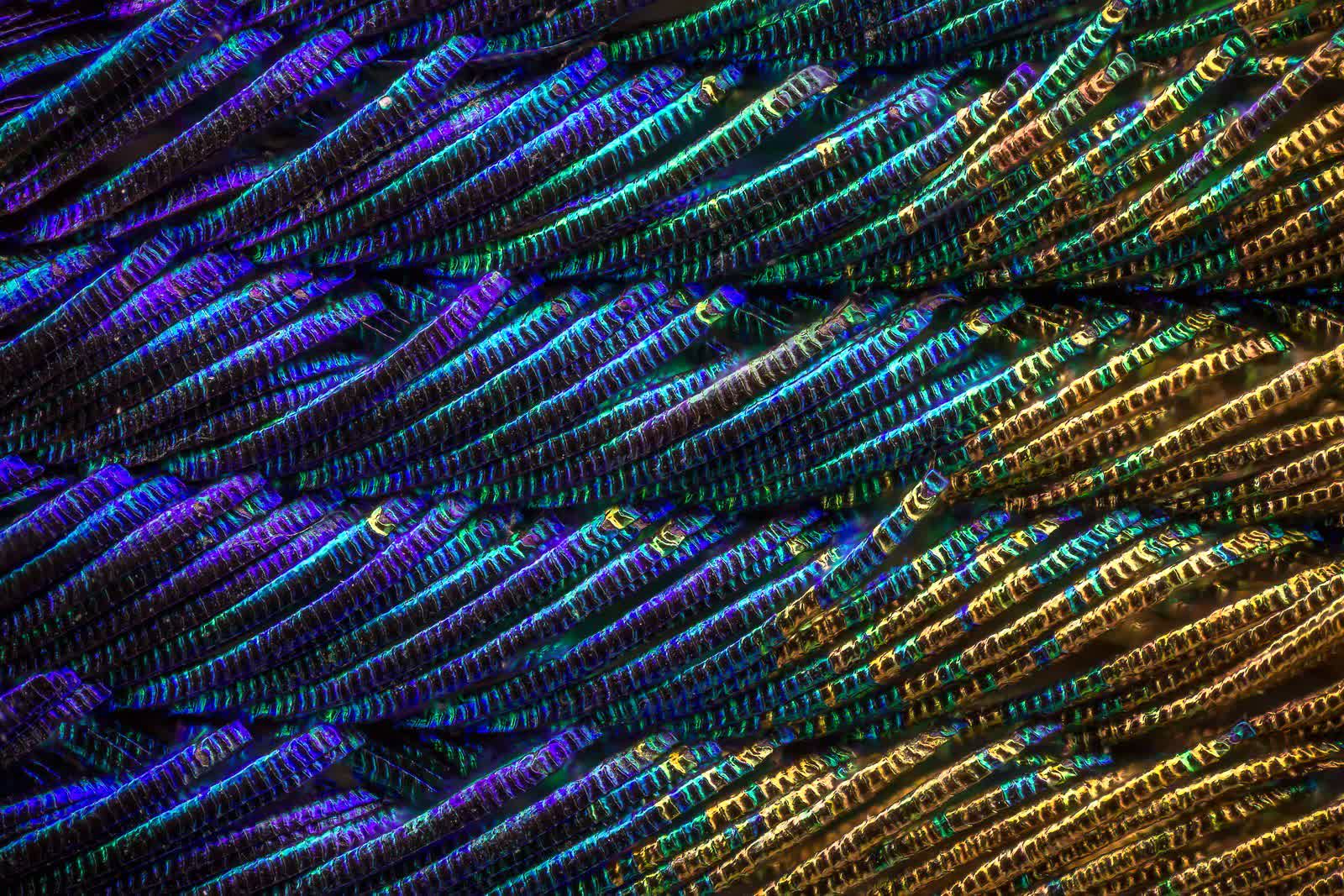

Take a peacock feather, for example. Submicroscopic ridges and contours in a peacock feather diffract light to create the iridescent blues and greens we see. This natural coloring is called structural color.

Scientists at the University of Central Florida have developed a "first-of-a-kind" paint that mimics the structural coloring we see in nature. Debashis Chanda, co-author of the study, "Ultralight plasmonic structural color paint," and his team accidentally stumbled upon the discovery.

The initial goal was to make a long continuous aluminum mirror using an electron beam evaporator. However, after numerous failed attempts, they noticed that the aluminum clumped together, creating microscopic "nanoislands." The bunching prevented the mirror from developing the highly reflective surface needed for a mirror. Chanda said, "It was really annoying."

Filaments of a peacock feather magnified 10x. Image credit: Waldo Neil

However, he noticed that the aluminum's electrons became agitated when ambient light hit the nanoparticles, causing them to oscillate. Furthermore, the electrons resonated with various wavelengths of light depending on the nanoparticle size. White light hitting the uneven surface bounced around its ridges before finally reflecting as a single color.

"Just by shifting the dimension[s of the nanoparticles], you can actually create all colors," Chanda told Wired.

So the team began working to create various colors of paint by growing aluminum nanoislands in a double-sided mirror, then specifically "dissolved" sheets of them into dust the consistency of powdered sugar. They then mixed the various colored materials with binders to make paint.

Chanda said that because of its structural nature, only a very thin coat is needed to color a surface. He says a drop the size of a raisin can paint both sides of a door. This property makes it ultralight, which could be extremely helpful in the airline industry.

A Boeing 747 requires about 1,000 pounds of paint. Chanda estimates it would take less than three pounds of his team's structural color to coat a jet, shaving over 997 pounds. It might not seem significant for a craft that weighs just south of a million pounds. However, just saving a little weight translates to massive savings in fuel.

"Given that fuel is already the single biggest operating expense [about 30 percent last year], airlines are always interested in improving fuel efficiency," said a spokesperson for for the International Airline Trade Association.

For example, American Airlines estimated that it saved 400,000 gallons of fuel and $1.2 million annually by removing only 67 pounds of pilot manuals from its planes. The company claims it saved another 300,000 gallons in 2021 by switching to a lighter paint that shed 62 pounds from its 737s.

Another advantage of this type of paint is its durability. Airlines repaint their planes up to four times a year because of the sun's oxidation effects. Structural colors don't fade in the sun, meaning repainting is only needed when you want to change colors.

One final property of the paint makes it helpful in keeping things cooler. Most planes are white to reflect as much light as possible. Absorbed infrared radiation becomes trapped, making the interior warmer.

Nature has various ways to add color. Structural scatting is the mechanic that Chanda's paint uses. Lamella nanostructures found in butterfly wings (and peacock feathers) scatter the blue components of incident light generating its characteristic metallic blue.

Preliminary tests show that the team's colorant keeps surface temperatures 20-30 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than traditional paint, regardless of the color. It's ideal for painting planes, cars, houses, and other buildings. If it can cut interior temperatures by even 15 degrees, it saves massive amounts of energy used for air conditioning.

The only problem the researchers face now is scalability. They have the equipment to make small vials but would have to produce much more to commercialize realistically. The lab is seeking commercial partners to help bring the paint to market.

Image credit: United Soybean Board