What just happened? A recently uncovered attempted bank heist illustrates the growing sophistication and audacity of cybercriminal operations targeting financial institutions. The incident involved a combination of physical intrusion, advanced malware, and anti-forensic measures to allow fraudulent ATM withdrawals from a targeted bank's network.

In a striking example of how the combination of physical compromise, network manipulation, and technical subterfuge is reshaping the threat landscape for banks and other critical infrastructure providers. This incident also highlights the importance of comprehensive security protocols that address both digital and physical attack vectors.

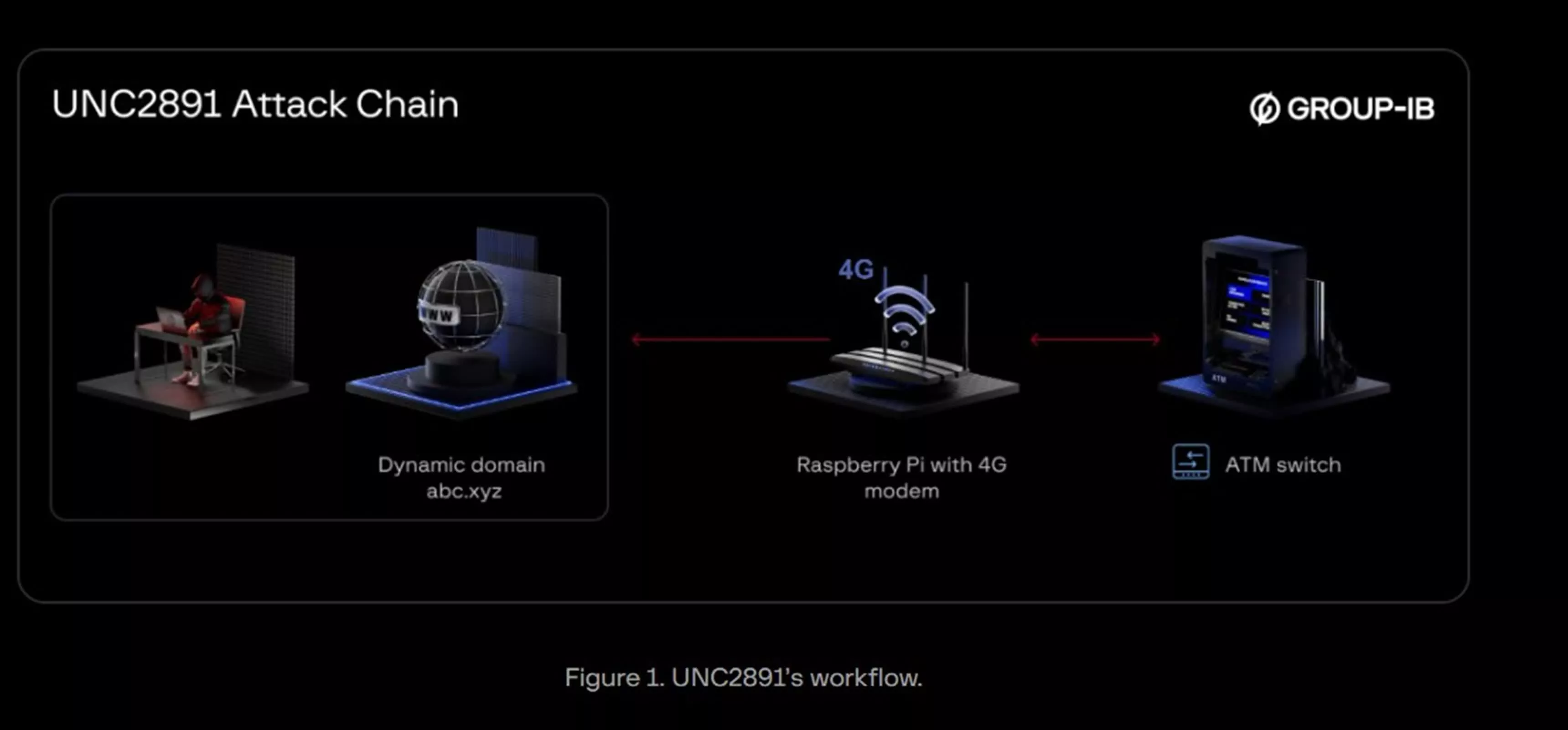

The investigation began when Group-IB observed unusual activity on a bank's internal monitoring server. Further analysis led to the discovery of a Raspberry Pi physically connected to the bank's ATM network switch.

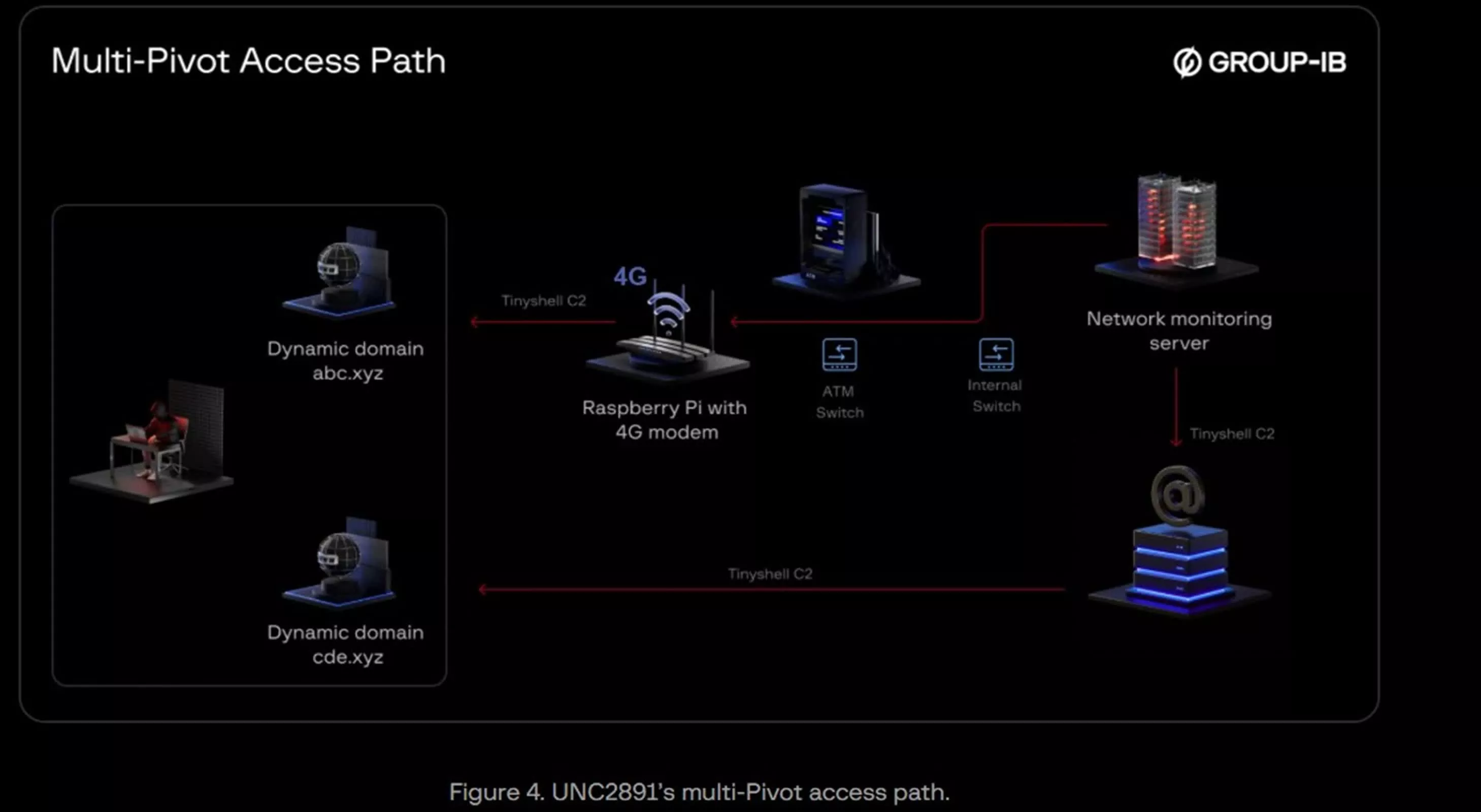

Equipped with a 4G cellular modem, this device provided a bridge between the bank's internal systems and external attackers, bypassing conventional network perimeter defenses. This setup offered persistent remote access via mobile data, even though the bank's firewalls were active and strictly configured.

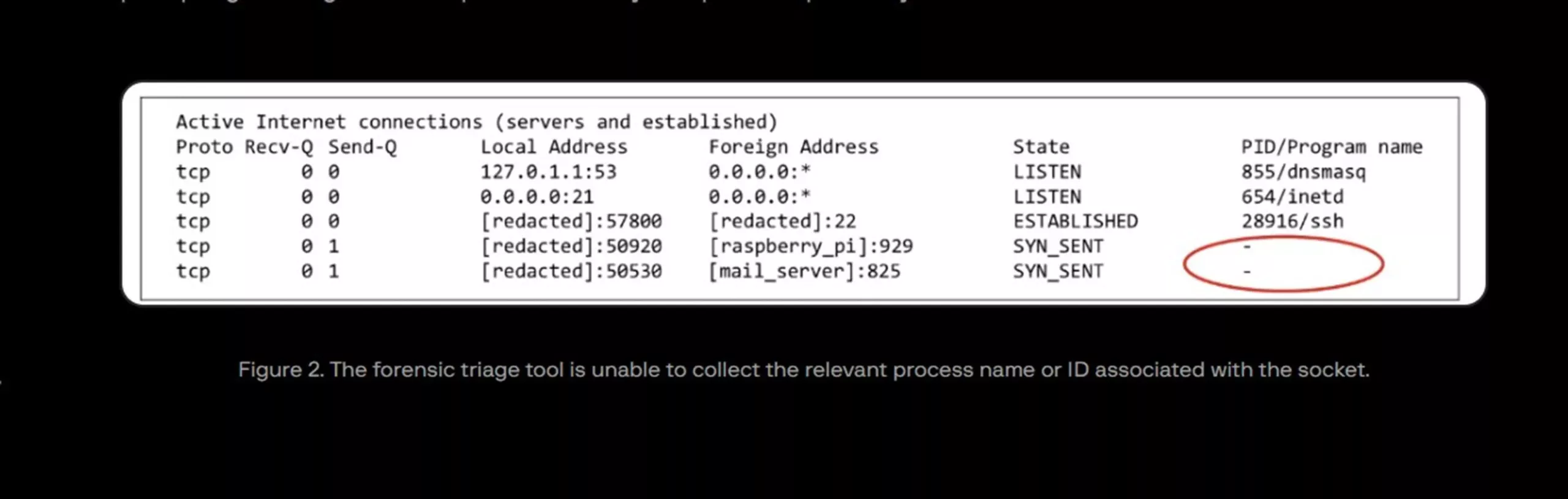

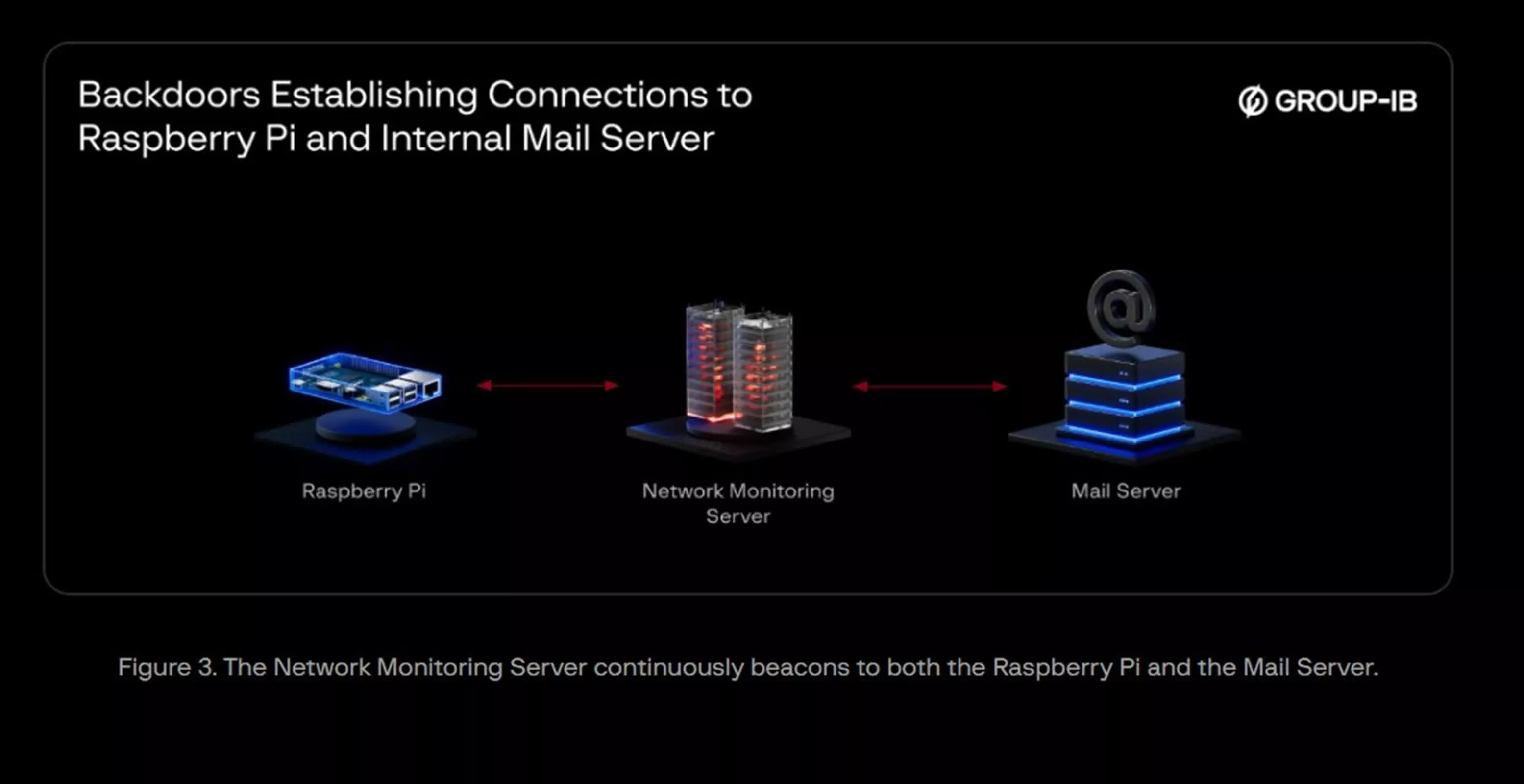

The attackers, who have been identified as UNC2891, which is also known as LightBasin, initially gained physical access to the bank – possibly through their own means or with the assistance of an insider – to install the Raspberry Pi stealthily within the ATM infrastructure. Once in place, the device served as a conduit, with the internal monitoring server repeatedly attempting data transmission to the Raspberry Pi over the local network every ten minutes. Forensic tools deployed by the investigators eventually traced these communications directly to the rogue device.

The attackers were able to move laterally by breaking into other essential systems, such as a mail server that was always connected to the internet. The Raspberry Pi and mail server, communicating via the monitoring server, expanded the attackers' foothold and resilience, allowing them to coordinate actions across the network even as the bank responded to the attack.

A distinctive feature of the attack was the use of custom backdoors disguised as "lightdm" – a name borrowed from a legitimate Linux display manager process. These malicious binaries were purposely placed in unusual directories and run with seemingly authentic command-line parameters to evade detection. This anti-forensic technique undermined monitoring that relied on checking system metadata.

The ultimate goal of the operation was to manipulate ATM authorization and execute fraudulent cash withdrawals. For this, the group attempted to install a custom rootkit known as CAKETAP – a malware component previously analyzed by threat researchers investigating UNC2891.

CAKETAP is engineered for Oracle Solaris systems and is designed to tamper with Payment Hardware Security Module responses. Specifically, it intercepts PIN verification requests and, for illicit transactions, substitutes legitimate authentication data, effectively performing a replay attack to bypass security checks and approve fraudulent ATM withdrawals.

As ingenious as it was, the heist was thwarted before the most damaging phase could be completed. Group-IB and collaborating investigators were able to neutralize the intrusion and prevent the deployment of the CAKETAP rootkit before significant financial losses occurred.

To avoid similar attacks, Group-IB advises banks to monitor mount and unmount system calls closely, alerting on any mounting of /proc/[pid] to tmpfs or external filesystems, and blocking or flagging executable files launched from temporary directories like /tmp or /snapd. They also stress the importance of physically securing network switch ports and ATM-connected equipment, and urge incident responders to collect memory images as well as disk data to improve detection and response to sophisticated attacks.