Why it matters: The past year has seen a gradual deterioration of the tech supply chain, to the point where unrelenting demand and a multitude of other elements have made it virtually impossible for industry players to catch up on the supply side of things. There are many factors that led to this situation, but one that has come into focus recently is that some companies are hoarding chips without taking into account the negative effects this practice has on the industry as a whole.

It all started with a shortage of chips that exposed a weakness in the global supply chain – a strong dependence on China and its neighboring countries for a large chunk of the world's manufacturing capacity for a variety of consumer and industrial products. At one point, manufacturers like Foxconn decried the situation and called for a concerted effort from governments and companies to develop a supply chain that is more resilient in the face of trade wars and major crises.

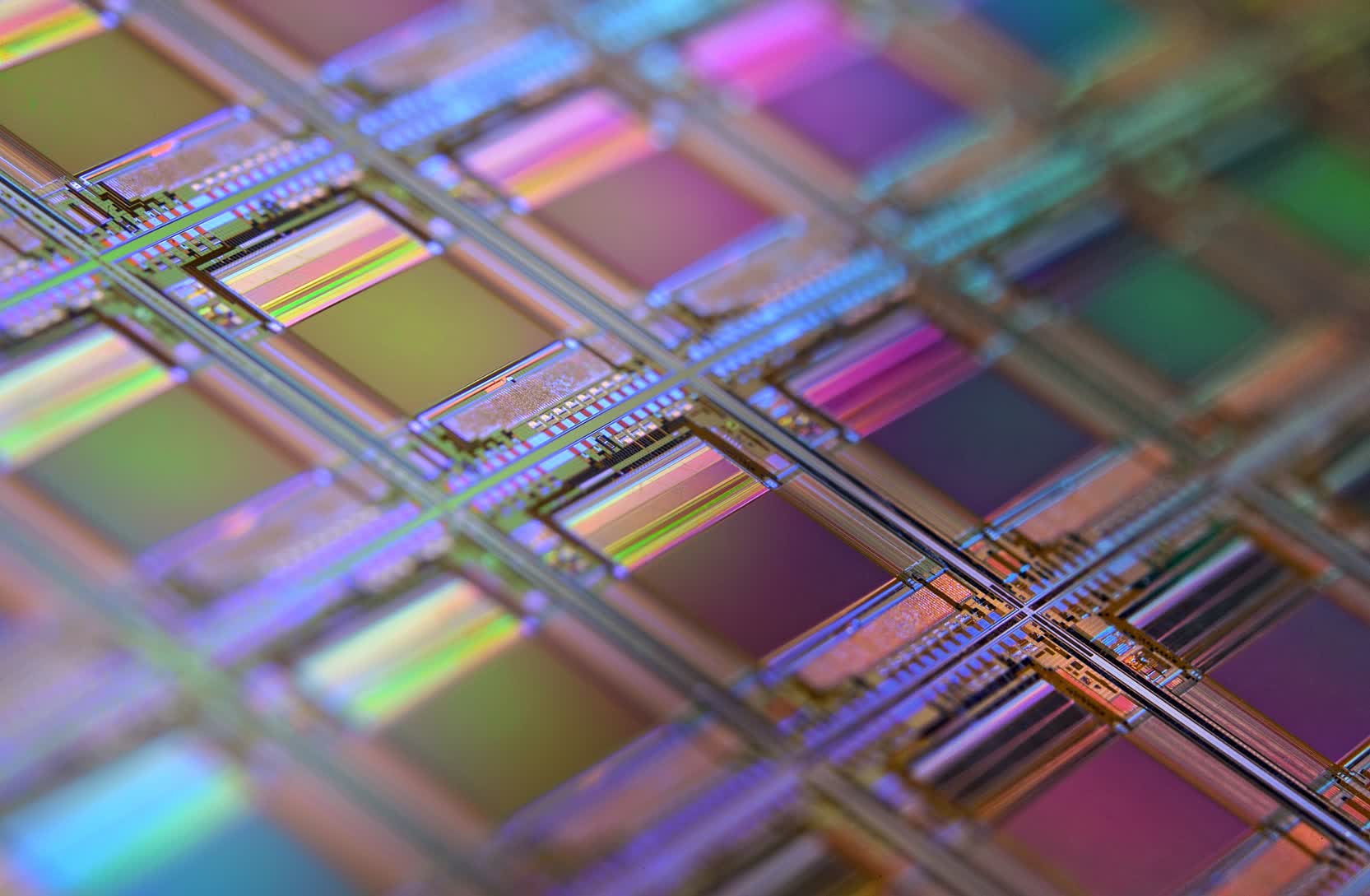

However, the situation is a lot more complicated than that. Chip foundries like Samsung and TSMC are firing up on all cylinders, but despite their best efforts, the most optimistic timeline for the supply catching up with demand is still 2022-2023. TSMC chairman Mark Liu told TIME Magazine that the company is doing whatever it can to serve all of its customers, and shot down allegations that TSMC is prioritizing one customer over another.

Liu says automakers were quick to point fingers at chipmakers for their $210 billion loss this year, but it's hard to determine exactly where the problem lies. For one, car manufacturers cut back production and reduced their chip orders in February, only to be faced with a surge in demand for their vehicles weeks after that. At the same time, TSMC reallocated some of its capacity for customers it thought were running out of stock.

This move didn't sit well with automakers and several other companies, but Liu said a likely explanation for the complaints is that distributors and middlemen are stockpiling chips. Despite the popular perception that TSMC is catering to Apple more than anyone else, in reality, it was forced to delay orders for valued clients who were deemed to have a healthy amount of stock for their immediate needs, in order to serve other clients who needed chips to stay afloat.

It's not hard to imagine where this is happening the most. At one point, Huawei spent billions on building a two-year stockpile of American chips to stay afloat amid rising trade tensions between China and the US. Other Chinese companies have pursued a similar strategy, but no one knows exactly how many chips they've been hoarding over the past year. What we do know is that China imported a record $35.9 billion worth of semiconductors in March alone to safeguard its local industry against US sanctions or other sources of disruption.

Liu notes the ongoing spat between the two countries isn't benefiting anyone and creates the perfect conditions for the current chaos in the global tech supply chain. TSMC's customers sign contracts for chip manufacturing well in advance, and the current political climate is forcing them to take desperate measures that further exacerbate the problem of chip shortages.

Also looming over the semiconductor industry is a lack of skilled workers, as well as booming prices for raw materials such as silicon and rare earth metals. If anything, it looks like solving the ongoing chip shortage is contingent on the ability of foundries like TSMC, Samsung, and Intel to expand the global manufacturing capacity – but governments also play a big role in how the industry navigates this process.