Why it matters: TSMC will spend $44 billion this year on capacity expansions, up from $30 billion in 2021. But while most industry leaders believe the chip shortage will ease slightly in the coming months, the true impact of these expansion efforts may not be seen until 2024.

Most chipmakers believe the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict won't worsen the global shortage of chips that's been plaguing the tech and auto industries. The supply chain has been showing some signs of recovery as of late, but industry leaders still are, at best, cautiously optimistic about the entire situation.

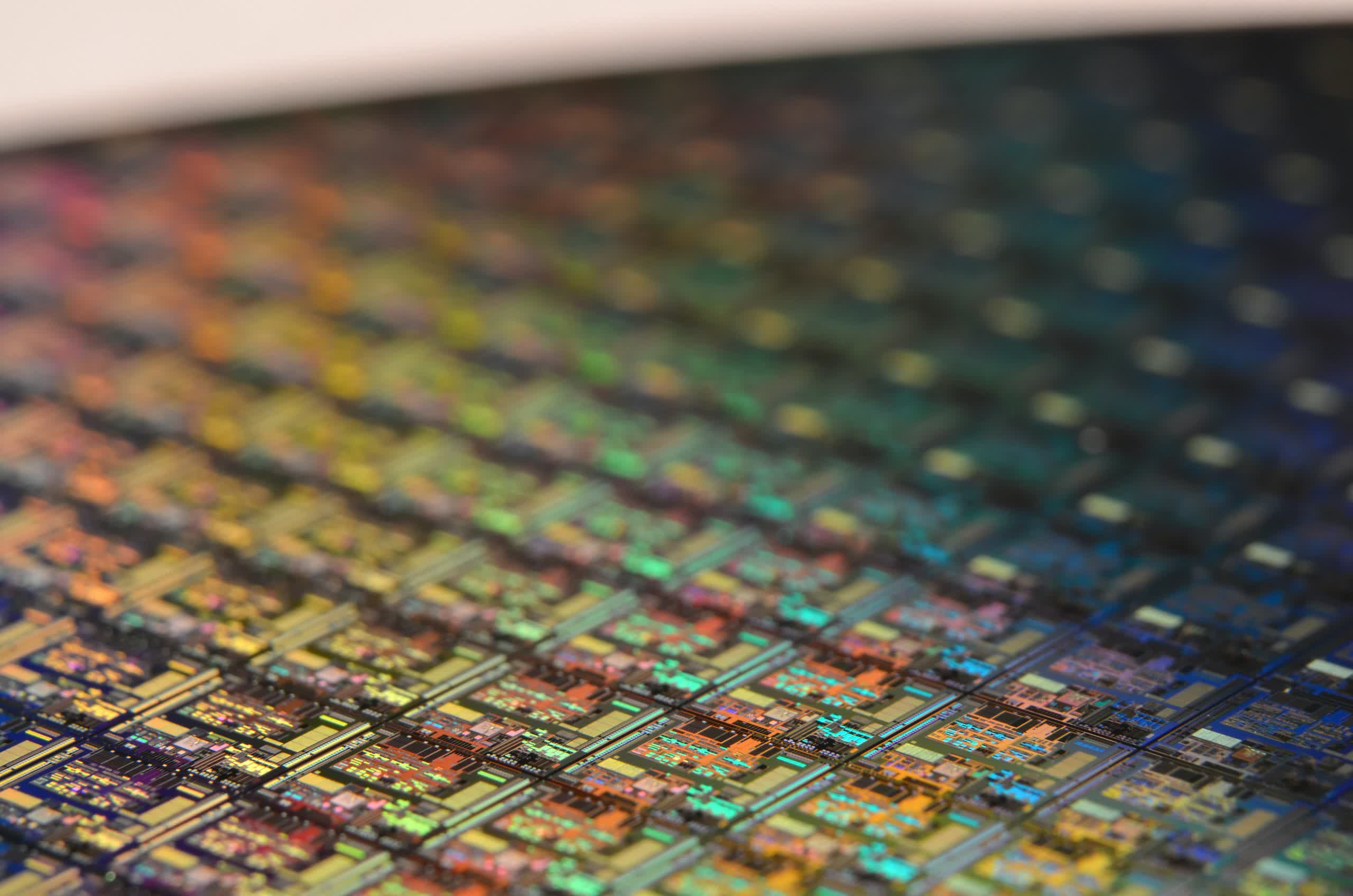

The chip industry is scrambling to diversify its supply of materials and gases and pouring billions of dollars into building additional manufacturing facilities and equipping them with cutting-edge lithography equipment. Still, these efforts take years to materialize and have a measurable effect, so experts are increasingly unsure the industry will be able to catch up with demand this year, or even in 2023.

Yuh-Jier Mii, who is senior vice president of research and development at TSMC, told IEEE Spectrum during a recent interview that he believes it's going to take two to three years before new factories will be able to help meet the demand for advanced chips.

This isn't the official position of TSMC as a whole, but the Taiwanese company has maintained that its foundries are already firing on all cylinders. Furthermore, TSMC chairman Mark Liu said last year that many companies were unprepared for the surge in demand that happened during the pandemic, so they started stockpiling chips, further exacerbating the shortage. In other words, the tech and auto industries will take time to adapt after operating under a lean supply chain model.

Interestingly, Mii believes the semiconductor industry missed the signs of growing demand spurred by the rapid digitalization of almost every key aspect in our lives. At the same time, he also mentioned the path to progressing foundries to more advanced process nodes is getting much harder with every new generation. What used to be mostly a "major optical shrink" now requires significant rethinking of transistor architecture, materials, tools, and manufacturing processes.

Meanwhile, a looming crisis of skilled workers threatens the efforts of chipmakers and electronics manufacturers to build additional factories and more advanced production lines.